Harvard Meta-Analysis Shows Statistically Significant Positive PrEP Effect from HCQ

The Chloroquine Wars Part CXIX

“Life’s tragedy is that we get old too soon and wise too late.” -Ben Franklin

A friend of mine (h/t) who works with the excellent c19early team, and who sends me a few timely research notifications, forwarded me this recently published meta-analysis on the prophylactic effects of hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) for the prevention of COVID-19 (García-Albéniz et al, 2022) a couple of day ago. I'll henceforth refer to this as the "Harvard meta-analysis" since the lead author and the biostatistician are both affiliated with the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. The Harvard meta-analysis found a statistically significant positive effect from prophylactic use of HCQ.

How could that BE when "GAME OVER" was declared on 17 different occasions?

It might be worth backtracking to see where all those kinds of suggestions came from, but that's not my focus for this article.

There are those who still hold the weird religious belief that meta-analysis (top of the pyramid, up near the all-seeing eye), and not experimental design, statistical modeling, or rigorous thinking, is the gold standard for science. It is also an unfortunately common belief that meta-analysis is currently performed in a generally high quality way. Science is about wisdom, not conforming to any organizational, methodological, or procedural template. Let us make a case study of this particular meta-analysis.

There is a lot to unpack here. This is a classic Spaghetti Western: There is the Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, all in one place.

But first, I'd like to share some less violent discourse about the nature and state of biomedical and epidemiological research with somebody who (1) is involved in the funding of medical research grants, and (2) expressed surprise at me on Twitter when he saw me tweeting about HCQ research (he thought that the case was closed)—like there were no signals of efficacy in the research. We talk about the Harvard meta-analysis, and some of the problems with the published and unpublished research surrounding HCQ during the pandemic.

Edit: YouTube deleted the entire Rounding The Earth account, but this particular discussion is here on Rumble.

One of the biggest problems we face today is that honest, well-meaning people rarely stop to share thoughts over disagreements and partisan boundaries. The chaos of the world has been more tense than usual. But when we stop for earnest discussion, the landscape around common ground, different sets of experience, and different interpretations of facts becomes a learning experience. Special thanks to Stuart for joining me, and for leading by example.

And now, onward with a discussion of the Harvard meta-analysis of HCQ prophylaxis.

The Good

The Harvard meta-analysis finds a statistically significant positive effect of HCQ as prophylaxis against COVID-19.

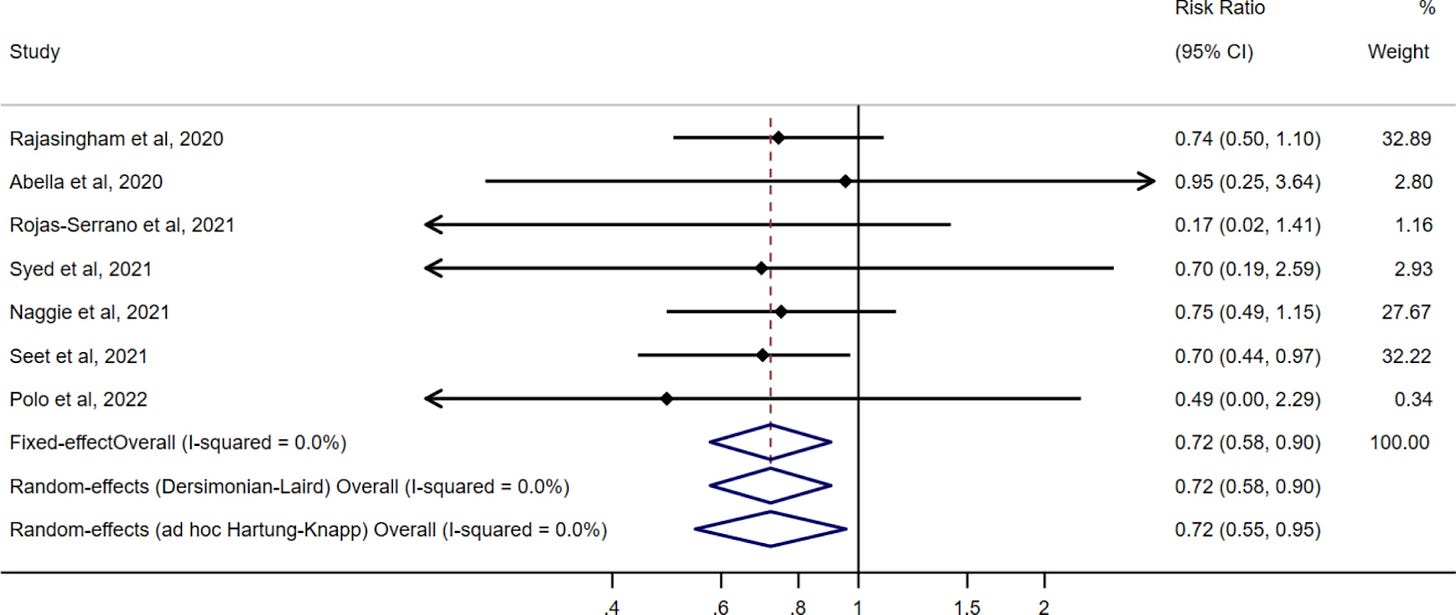

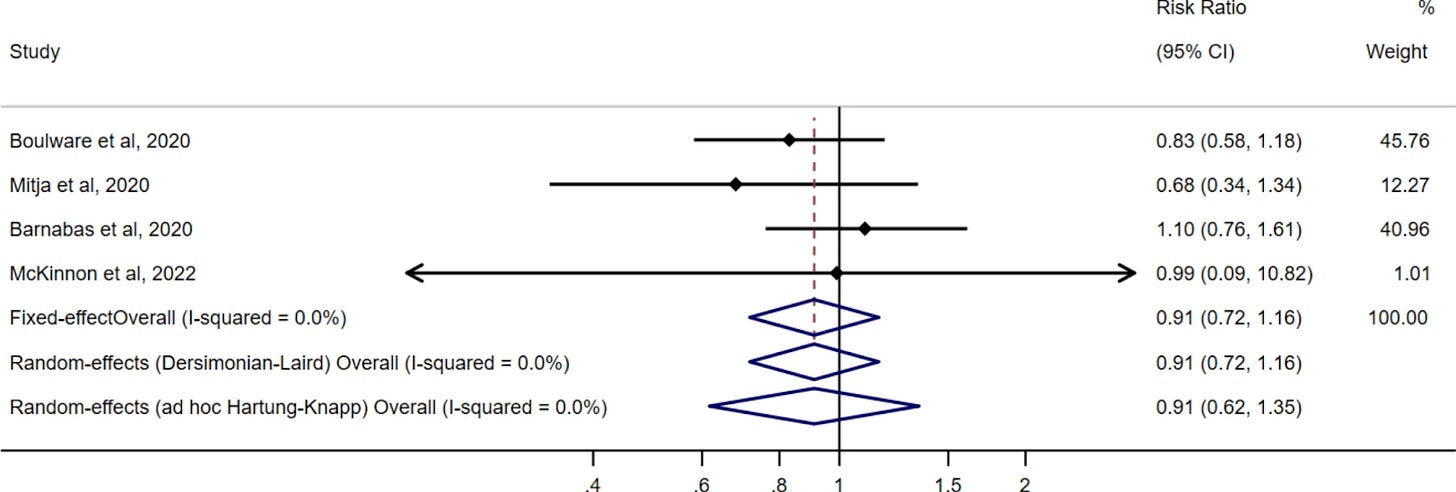

The pooled risk ratio estimate of the pre-exposure prophylaxis trials was 0.72 (95% CI: 0.58–0.90) when using either a fixed effect or a standard random effects approach, and 0.72 (95% CI: 0.55–0.95) when using a conservative modification of the Hartung-Knapp random effects approach. The corresponding estimates for the post-exposure prophylaxis trials were 0.91 (95% CI: 0.72–1.16) and 0.91 (95% CI: 0.62–1.35). All trials found a similar rate of serious adverse effects in the HCQ and no HCQ groups.

Of course, for those following the evidence closely, it's hard not to find a positive effect, no matter how picky and choosy you are with your claimed beliefs in which data is worth 100% inclusion and which data is worth 100% exclusion in such a meta-analysis.

https://hcqmeta.com/

When we focus in on the negative trials, we find almost every one of them to be generally smaller or focused on patients with immunological disorders, not the general population. The remaining positive evidence is overwhelming, though much of it gets dismissed by the Harvard meta-analysis.

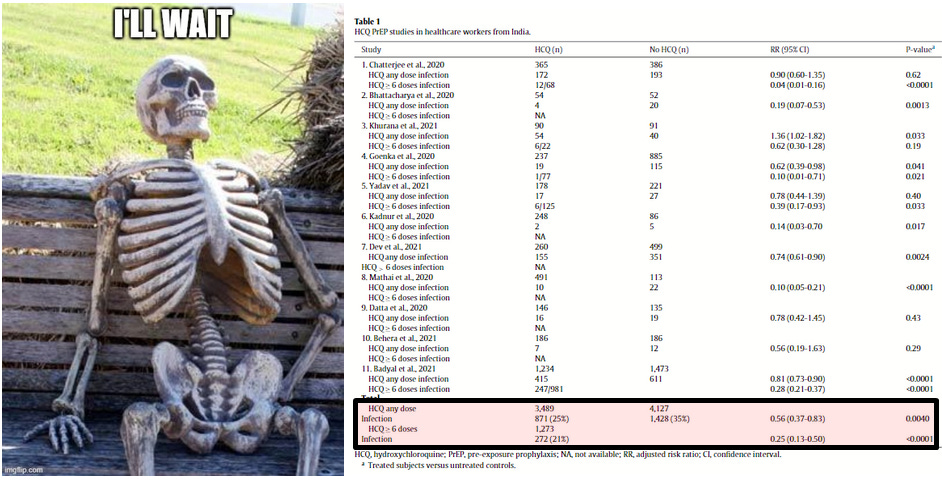

Also, the meta-analysis published last year (Stricker and Fesler, 2021), which I will call "the India meta-analysis", that focused on 11 studies out of India found both consistency and dose dependence of effects. None of this evidence was included in the Harvard meta-analysis.

But it's a good thing that this is all finally settled by people at Harvard. Now we're going to hear apologies from all those people who called HCQ snake oil thirteen seconds after Trump spoke about it, right?

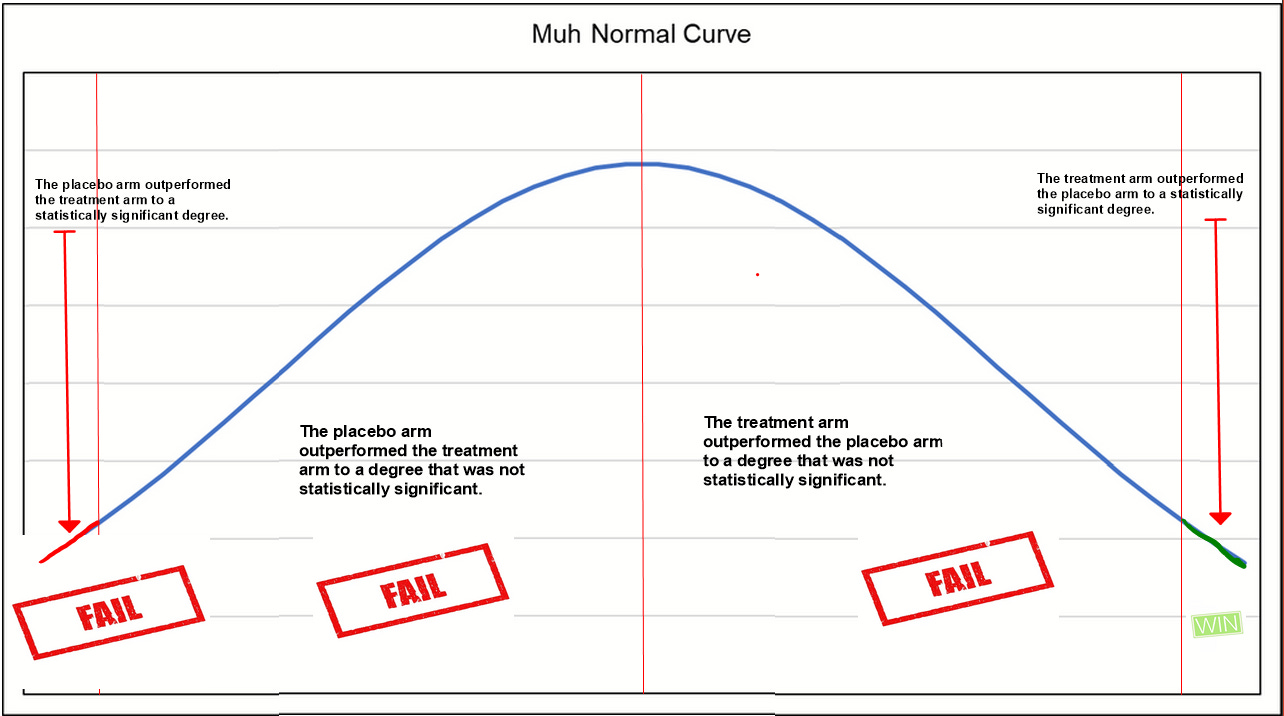

During 2020 most of all, and still since, one of the most absurd arguments (ever made in the history of biomedical pseudo-statistics) was that the lack of statistical significance in one or several trials was the equivalent of "failure" (of the HCQ hypothesis).

The authors of the Harvard meta-analysis speak out about the clearly absurd notion that not previously having a statistically significant positive effect in meta-analyses or even a single trial represented failure of the hypothesis.

A benefit of HCQ as prophylaxis for COVID-19 cannot be ruled out based on the available evidence from randomized trials. However, the “not statistically significant” findings from early prophylaxis trials were widely interpreted as definite evidence of lack of effectiveness of HCQ. This interpretation disrupted the timely completion of the remaining trials and thus the generation of precise estimates for pandemic management before the development of vaccines.

It should not even need to be said now stupid such an interpretation is, and we should not be so naive to conclude that this was an accident given the production level of the show trial that HCQ got in the media.

Back to the Harvard meta-analysis…

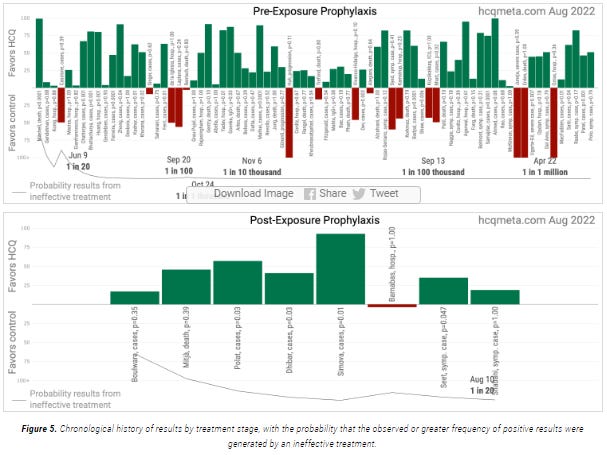

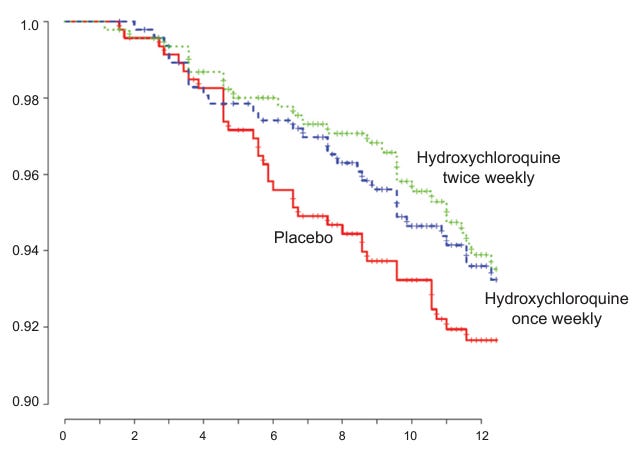

Consider: the following two charts demonstrate the primary focus of the paper.

The summary of the effects from the selected pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) RCTs:

The summary of the effects from the selected post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) RCTs:

It should not surprise anyone that the PrEP trials show superior effects to the PEP trials. It is hard in a PEP trial to determine with certainty when viral infection actually occurred. But the results should be viewed as correlated, and support one another as evidence of mechanism in the prevention of COVID-19.

The Bad

The bias in the Background section appears quite obtuse:

Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) is not an effective treatment for established coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1, 2], but it is unclear whether HCQ can prevent symptomatic COVID-19.

The two citations refer to the World Health Organization's trials, which tested HCQ in ways that can be at best described as baffling, and at worst criminal. No physician in the world used HCQ the way it was used in those trials, and no honest and informed scientist or statistician can take them seriously. If I'm wrong, I would be happy (thrilled) to have a recorded conversation with one who does. And if the authors were somehow unaware of this controversy, then there are a lot of important questions to ask, like

Shouldn't this meta-analysis be conducted by experts on the research?

Shouldn't we expect more from Harvard?

What does it mean that we don't get it?

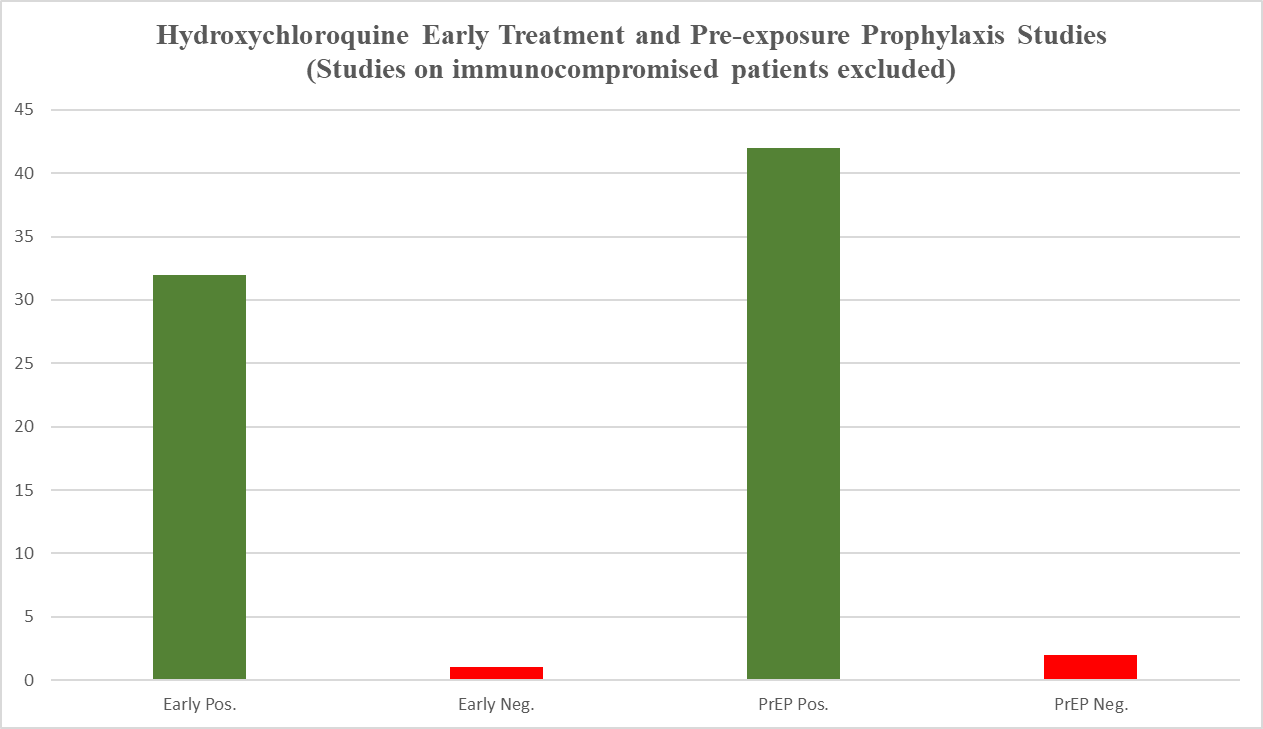

Friendly reminder, this is where the collective research for PrEP and early treatment studies stood in December after removing the studies of largely or wholly patients with immunological disorders:

Only a few studies have been published since that time, so I doubt this 96% positive (as in the treatment arm outperformed the placebo arm) ratio changed dramatically in the meantime. If positive results would happen 50% of the time at random (not precise, but a close estimate), this result would take place less than 2 out of a million million million times.

Next, according to the authors of the Harvard meta-analysis,

For each of the identified trials, we obtained or calculated the risk ratio of COVID-19 for assignment to HCQ versus no HCQ (either placebo or usual care) among test-negative individuals at baseline.

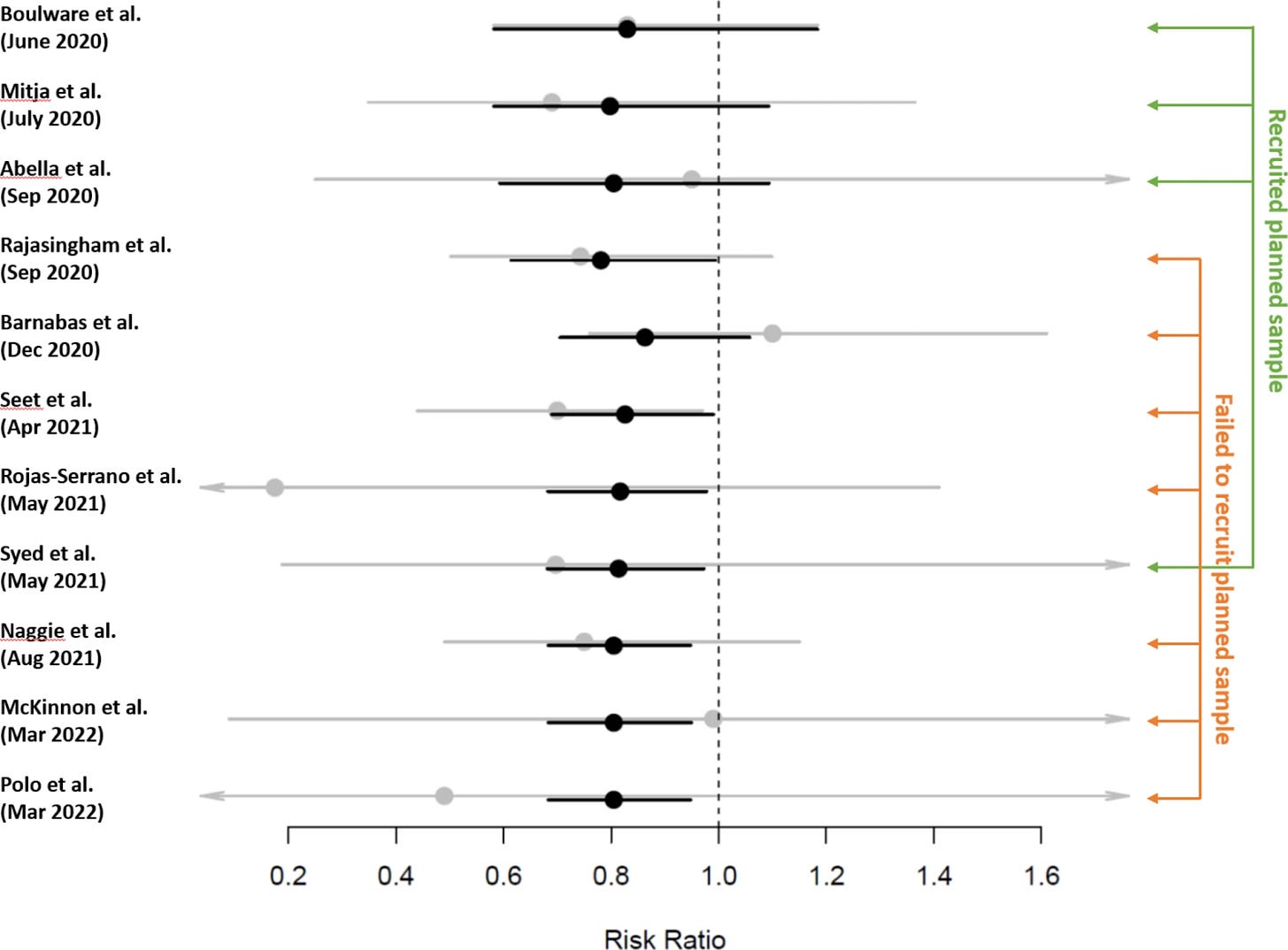

However, they included both the Rajasingham study and the Boulware trial, arguably neither of which satisfied this criterion due to using potentially reactive agents. Not only has folate been observed in the literature to have antiviral effects (Trushakova, 2019), but Iranian researchers had already uploaded to preprint (Shebanyi et al, 2020) a paper in March 2020 theorizing a mechanism by which folate inhibited the furin cleavage activity of SARS-CoV-2. The potential of folate as an active agent should call into question the inclusion of these studies, and the level of bias of the researchers themselves—particularly when its use as placebo was entirely unnecessary. This public challenge to the Boulware and Rajasingham methodologies at least warrants a mention.

The Ugly

This is more general commentary on the way meta-analyses get conducted, which strikes me as a lazy cookie-cutter method that sidesteps some obvious problems that would be avoided with good first principles thinking. I am always at a loss for words over several aspects of meta-analyses that result in twisted representation of the body of evidence:

The binary inclusion/exclusion of data. The credo of a data analyst should be that all data is valuable. Why not throw weights on the data, then run it through the chosen statistical rubric?

The lack of a feedback loop that goes back and re-assesses the value of weighted/excluded studies based on the results of those first selected as high quality. A meta-analysis that snobbily includes only RCT data would do well to analyze the similarity of results with the OCTs since historically such results do usually converge. In this case, we would then have a pool of evidence with consistent dose and temporal effects that would clarify the analysis tremendously.

In almost all cases of hundreds of meta-analyses I've read, no attempt is made to estimate the effect of a/the optimal protocol. This results in a generalized underreporting of the most important effect size, which would be at least as good, and nearly always better than the effect size reported in the meta-analysis of all protocols.

As I've previously noted, there is nothing particularly objective or even consistent in the grading of research for inclusion in meta-analyses, and nothing stops the process from being biased in even disturbingly obvious ways. As such, elevating meta-analyses to the top of the food chain of scientific evidence makes it the easiest target for evidentiary manipulation. For this reason, we should hold meta-analyses to higher standards, or otherwise label them as "rapid reviews" to make clear that a deeper analysis could and often should be performed.

Why not use all the data, but with weights that display relative confidence?

I like to say that, "all data is valuable," but that it's up to the problem solver to best interpret it and make use of it.

This problem in binary judgment is not dissimilar to the (very reasonable) critique over the brightline conferring of "statistically significant" status on a result where p = 0.049, and not for a result where p = 0.051. We really just accept one of these results as fully meaningful, and toss the other in the trash?

Dumb. In both cases.

Fisher picked 0.05 for reasons of time economics, and we should expect that experts in their fields can assess the evidence in ways other than some computed p-value.

Nobody whose job depends on the best use of data operates the biomedical scientists and statisticians do in these kinds of aggregate analyses. This is exclusively a problem in the most corrupt or silly corners of "the science".

What about the evidence of borderline quality that got excluded, but fits the results of the meta-analysis?

When our concerns over research are allayed by their consistency with a larger body of results, we might consider a feedback loop of analysis and perform a second run of the overall data. This is like the Yankees calling up a kid in the minor leagues who appeared undersized at training camp, but for months just keeps on hitting the ball well, and with power.

The authors of the Harvard meta-analysis note that the inappropriate declaration of negative experimental conclusions resulted in poor recruiting in further trials (which anyone paying attention either already knows, or knows that it was an excuse to discontinue, for instance, the NIH and Duke trials).

Great, but they should have been calling major news outlets, and explaining the need to call the dogs off. We are humans with responsibilities, not specialists trapped in a maze.

What's this thing about the "most important effect size" of the optimal protocol?

Glad you asked, mysterious voice.

Most people reading meta-analyses take the reported risk reduction or odds ratios to suggest what we should expect from the drug. In my experience, even most of the people I've talked to who write such analyses make that mistake of interpretation. This is where dogma and indoctrination likely creates a bubble, and keeps people from thinking clearly and naturally on their own.

A more valuable meta-analysis would first suggest the likelihood of an effect, and would then regroup the evidence by protocol and compute the aggregate effect size for only the optimal protocols. Wouldn't you rather know the effect size of the best protocol, and see it side-by-side with the aggregate effects of all the different protocols? Who wouldn't?!

Even individual studies invite such an analytical step, and compute multiple effect sizes. This could have been done in the Rajasingham study for instance:

And the computation of optimal protocol effect size was reported in the India meta-analysis on India's HCQ PrEP trials (dose dependence separated the two effect sizes).

The meta-analysis community is a complete mess. This seems largely due to a combination of the influence of the Pharma and Public Health communities. It's not just that the methodologies lag far behind the time—in most technical disciplines, there is more of a jeet kune do/MMA/free form approach to the statistical jujitsu, where important problems are always evaluated from first principles. It's that even most of the best of the published meta-analyses are paper thin, and more often than not heavily biased.

For 2.5 years hydroxychloroquine was ignored. And didn't the FDA get the Ivermectin meta-analysis from Tess Lawrie in August 2021 and ignored that?

Isn't mass murder a crime against humanity any more? We need to stop believing the government is above the law.

https://journals.lww.com/americantherapeutics/fulltext/2021/08000/ivermectin_for_prevention_and_treatment_of.7.aspx

Didn't need those meta-analyses anyway. Since millions of prior treatments had been safe for decades, the anecdotal reports were sufficient: May 2021, Uttar Pradesh, 97% reduction after five weeks of Ivermectin.

https://www.hindustantimes.com/cities/lucknow-news/33-districts-in-uttar-pradesh-are-now-covid-free-state-govt-101631267966925.html

You don't wait for unnecessary meta-analyses during a battlefield crisis. That they did is prima facie evidence of mass murder, as well as some nefarious agenda.

Great article and analysis! I wish more (or all) researchers/statisticians would be like you! Our world could be a much better place if we had more Mathews like you.