"History is the best teacher, who has the worst students." -Indira Gandhi

In our last article, we demonstrated RCTs are neither the highest form of scientific experimentation, nor are guaranteed to achieve their goal of proving superior testing. In this article, we examine the empirical history of RCTs, and compare the data from RCTs with "lesser" forms of experimental data.

In a paper published in the Annals of Medicine in November, 2017, Alexander Krauss analyzed the 10 most commonly cited RCTs in medical literature--each with thousands of citations and substantial impacts on public health policy--and found them replete with unexamined limitations, biases, and failures of randomization. He concluded that focusing on RCTs as the “only reliable research design” would lead to “neglect” of other issues “that are studied using other methods (e.g., longitudinal observational studies or institutional analysis).” (Emphasis ours.)

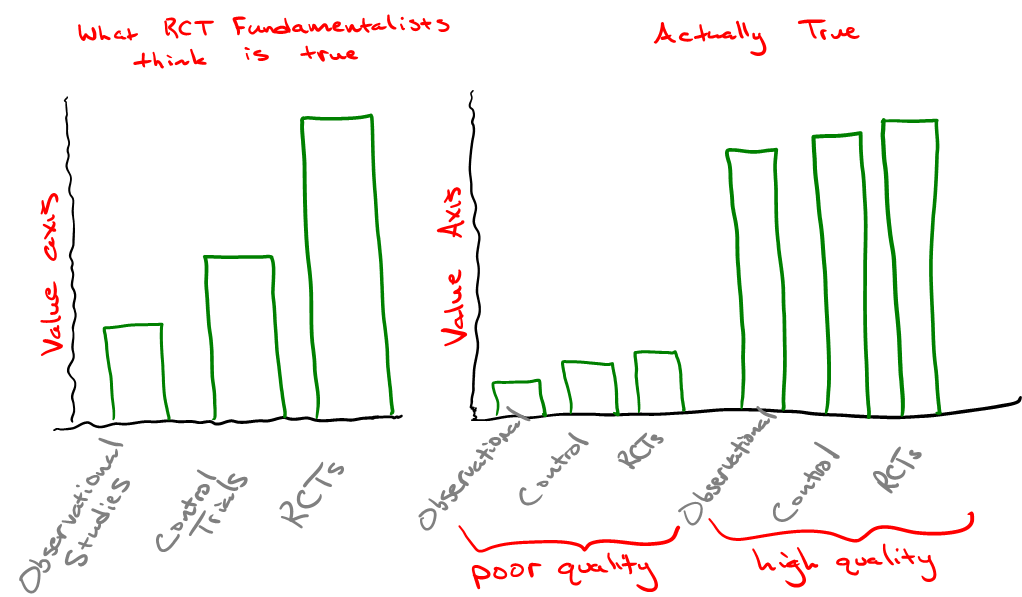

In an NEJM publication authored by epidemiologist John Concato and colleagues in 2000, the authors found that of 99 reports on five clinical topics, “the average results of the observational studies were remarkably similar to those of the randomized, controlled trials.” In fact, the authors noted that results from observational studies on vaccines resulted in tighter “point estimates” (confidence intervals), a measured probability range that helps researchers understand the bounds of an experimental result in a random model. This has at least something to do with the greater cost (in direct economic terms) of obtaining each data point collected in an RCT. And more data points mean greater certainty (tighter confidence intervals).

Even more to the point, aggregating vast amounts of data from numerous observational studies performed on different populations can “balance” both known and unknown confounders far better than can an RCT with a fraction of the number of participants. Remember our practical credo on data:

Regardless of all else, seek ways to make the greatest net value out of all data.

Oftentimes, it is easier to reach confidence with many good, but imperfect data points than it is to reach confidence with few nearly perfect data points. And while the historical data bears that out, we should fully expect it!

Plenty of RCTs have failed in their goal, whereas much great science has been done without them. This disparity may relate to experimental design, but it might also relate to the analyst. It is the job of the analyst to make the best use of the available data. A superior statistician with an inferior data set is nearly always preferable to an inferior statistician wielding the most pristine data possible (and no respectable statistician would argue that point). Only a foolish statistician would start work with less than a full data set, from all experiments, given the option.

The skeptic: So why then do all the experts say they don’t trust results without an RCT?

They don’t. No matter how much writers in the media tell you what Dr. Fauci thinks, and vaguely refer to his opinions as those of “all” or “the majority of” scientists or statisticians, the only field of science in which people (foolishly) talk that way is in pharmaceutical medicine. This claim is not backed by history or reality, but by money. Once upon a time statisticians objected to the claim that RCTs were necessary to prove that smoking causes lung cancer. We should have taken that moment to forever put the myth of the need for the “gold standard” RCT to rest.

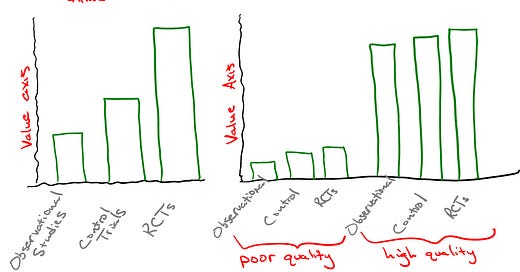

Psychiatrist Norman Doidge refers to this attitude that rejects all other forms of evidence as “RCT fundamentalism”. In his article, “Medicine’s Fundamentalists”, Doidge noted that RCTs can confound by design. The criteria by which some patients are excluded from a study may change results in unexpected ways. Doidge observed that 71.2% of RCTs were found not to be representative of real world patient circumstances, and that 35% of their findings were not replicated when tested a second time. Larger data sets help with this problem.

So, just how did RCT fundamentalism take root?

The very first RCT took place only in 1948 after British statistician Ronald Fisher spent more than two decades paving the way with a statistical framework for measuring and interpreting outcomes while testing hypotheses through observed experimental test results. Gradually, more and more RCTs took off over the years. In preparation for this article, I conversed about the history of RCTs with medicine manufacturer Monica Hughes who noted,

RCTs didn’t exist much before the 1960s Kefauver Harris Amendment to the FDA. It’s not how the vast majority of medical innovation was ever done, and the FDA itself only existed until 1962 to assess safety, not efficacy.

Since that time, some medical treatments, most often in the realm of pharmaceutical therapy, have been accepted into practice because of RCT results. And also many without them. Although Dr. Raoult’s twelve [disease therapies developed] stands out as a colossal achievement, never in his career did he run an RCT. His many successful treatments achieved widespread acceptance without them.

RCTs took root in pharmaceutical and vaccine testing over the past few decades. They were the best way to sell both consumers and regulatory agencies on new medicines. That probably has something to do with the long history of phony cures peddled by pharmaceutical salesmen over the years. But such history is often quickly forgotten, and slogans become psychologically self-reinforcing until they become the new official myth. Gradually, the methodology became more widely applied, successfully or not, until those who believed in its superiority saw it as the bright line standard by which data are accepted or rejected in analysis (where convenient for the bottom line).

We might ask ourselves: Were RCTs conducted to determine whether lockdowns or masks inhibited the spread or severity of SARS-CoV-2 before scores of nations made those decisions? No. Ultimately, nearly all practical decisions are made on the best data available, and quite often that data speaks loudly (more so for HCQ than for either masks and lockdowns). Judgment and decision making have always lived, and will likely always live, in a zone somewhere between art and science. Strangely, the RCT fundamentalists never spoke up on these topics. It is likely that political heuristics take precedence in most minds at such moments.

Nobody suggests running RCTs to determine the efficacy of schools, the safety of automotive vehicles, or whether or not higher rates of death among methamphetamine users is due to the drug or some other correlating factor. Nobody decides to teach their children how to safely cross the street by running RCTs. As Doidge points out, it was observational studies that taught us that Sudden Infant Death Syndrome occurred more often in babies put to sleep on their tummies instead of their backs, and that observation saved lives. Common sense dictates that we make the best forms of data and information available as valuable as we can within the best economic framework we can muster.

Look outside of the medical industry, and what do we see? The primary reason for the Information Age is that technology now allows us to make use of more and more data---even mundane data. Our most successful industries---technology and finance---have no such heuristic for rejecting data not passed through the rubric of an RCT. Where economical, these industries perform AB testing and other randomizing sieves. And so too can an adequate statistician perform techniques to achieve better randomization without an RCT. Propensity score matching is one such example.

Why then does the pharmaceutical industry and its promoters insist on conducting RCTs before something is accepted as true? RCTs take substantial amounts of time and significant resources to conduct. This creates a barrier to entry, especially for inexpensive solutions to medical problems. In other words, the myth that RCTs are some necessary "gold standard" is a deception that, along with regulatory agency, prevent any possibility for simpler and less expensive (less profitable) medical solutions to gain traction.

Used judiciously, RCTs can certainly have their place in productive science. They may provide value aside from slowing down competing solutions, such as when there is a desire to identify subgroups sensitive to a new medication. But the idea that RCTs uniformly provide substantial value to the results of an experiment, much less fulfills a necessary criterion, is an engineered mythical axiom that runs counter to the general scientific experience. Rejecting RCT fundamentalism should be easy for the practical thinker.

As someone who spent 13 years running a clinical trial repository of my own design, I’d about given up trying to catalogue the ways in which the ‘ethical pharmaceutical’ industry and Google have conspired to lead a disinterested press corps around by the nose. I greatly appreciate your work here.

I was expecting to see a discussion of the 2nd reason for RCT preference, besides serving as barrier to entry. It's also easier to twiddle RCT design parameters to obtain desired goal -- either to boost one's own drug or to suppress another one. Is this discussed anywhere in the book?