Dose Dependence in the Hydroxychloroquine Prophylaxis Research

The Chloroquine Wars Part LXXIV

"People almost invariably arrive at their beliefs not on the basis of proof but on the basis of what they find attractive." -Blaise Pascal

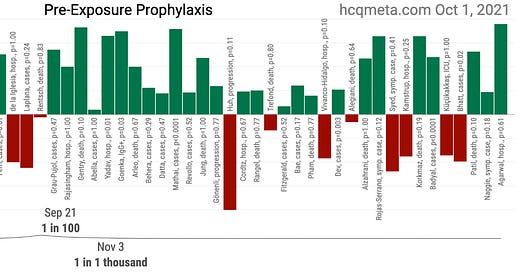

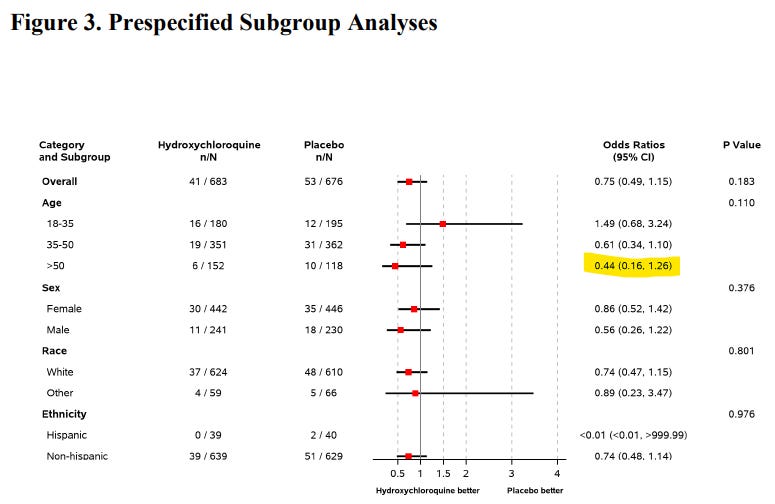

Over the past few months I largely stopped reading new research papers on chloroquine's (CQ's) or hydroxychloroquine's (HCQ's) protection against or treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection. But after recent contact with one of the authors of a new meta-analysis (Stricker and Fesler, 2021), I decided to take a second look and wanted to share my thoughts. Before I discuss the Stricker and Fesler paper, I'd like to zoom out a bit. The following graphic displays the broad summary of research into CQ/HCQ pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for COVID-19. Since nearly all of the research focuses on HCQ, I will combine the abbreviations moving forward.

Thanks to the people behind c19study.com and hcqmeta.com, we have great summary resources for the research to date. If you know of any research not included, please leave a comment. On a superficial level, we might first note that out of 56 published studies on HCQ prophylaxis in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection, COVID-19, or its effects, 42 of them (75%) are positive, though individually these studies are often too small to reach statistical significance.

When examining a body of data, one of the first things I like to do is look for some variable or characteristic that distinguishes outcomes. In this case, that characteristic is easy to observe.

All 14 Negative HCQ PrEP (SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19) Research:

Huh et al, 2020 (South Korea, retrospective case control)

Cassione et al, 2020 (Italy, retrospective of systemic lupus erythematosus patients)

Singer et al, 2020 (USA, retrospective of auto-immune patients)

de la Iglesia, 2020 (Spain, retrospective of auto-immune patients)

Laplana et al, 2020 (Spain, survey of chronic CQ users/auto-immune patients)

Rentsch et al, 2020 (UK, observational cohort study of auto-immune patients)

Huh et al, 2020 (South Korea, retrospective database analysis of prescribed medications)

Trefond et al, 2021 (France, retrospective of systemic auto-immune patients; preprint now removed by author request)

Vivanco-Hidalgo et al, 2021 (Spain, retrospective database analysis of chronic HCQ users)

Alegiani et al, 2021 (Italy, retrospective database analysis of rheumatic patients)

Syed et al, 2021 (Pakistan, RCT (?) among healthcare personnel)

Kamstrup et al, 2021 (Denmark, retrospective database analysis of prescribed medications)

Kucukakkas et al, 2021 (Turkey, retrospective of rheumatoid arthritis patients)

Bhatt et al, 2021 (India, retrospective study of health-care workers)

What jumps out immediately is that likely 12 of these 14 studies were on patients largely or entirely consisting of sufferers of auto-immune disorders. In other words, there are almost zero negative HCQ PrEP studies examining HCQ's effects on healthy individuals. And in fact, all 12 of these studies may show positive results when the (statistically significant) increased risk of COVID-19 found in a study by Ferri et al (2020) is taken into account (OR 4.42). While some authors opine on the reasons why HCQ fails to work as PrEP for patients with auto-immune disorders, I'd like to hold back on the assumption that it doesn't.

But it may very well be the case that HCQ does not work as PrEP for patients with certain auto-immune disorders who use the anti-inflammatory/immunomodulator chronically. This could be for a number of reasons, including the body's response to the constant presence of the drug in terms of acting as a zinc ionophore. It would be interesting to know if zinc supplementation of some sort would make a difference, or whether there is a cross-process that could be identified and modified in order to reconnect the body's mechanism to pushing zinc into cells.

On another note, given the high proportion of overall positive studies on HCQ efficacy, these studies on auto-immune patients stand out. Certainly, there seems to be a lack of interest in displaying results in a way that takes the Ferri research into account, but it should be noted that such retrospective studies can be easily performed without publication. In other words, those with access to databases, which would most often be pharmaceutical manufacturers and researchers who work with them, could scan for cohorts that show an on face negative results, and publish only those. I'm not saying that happened (how could anyone know), but it's worth keeping in mind when taking a body of evidence into account. These studies make up the weakest pool of evidence, and on several levels.

Now, let's take a look at the other two negative HCQ PrEP studies. The Syed RCT (?) stands out as a different kind of evidence. The PrEP regimens used (there were three) are unlike what has been used in any other protocol or research I've read, with participants taking medication only once every three weeks. Elsewhere, 400mg to 600mg per week seems more standard. And with some patients receiving medicine weekly, and others every third week, and just one placebo group, the design of the study seems to contradict the definition of blinding. I've never before seen that particular mistake in study design, hence my (?) after its description, and there is no way to know how that might have affected the behavior of the trial participants. The results of the study were mixed, with some endpoints showing efficacy and others not.

The Bhatt study is still in preprint, and some problems with the study stand out. In particular, adherence to the HCQ protocol was extremely weak, with almost no participants continuing after 11 weeks. As we will see later in this article, there is noticeable temporal dose dependence in studies showing positive HCQ PrEP efficacy that suggests that full efficacy takes around six weeks of accomplish. However, only 18% of 731 participants were still taking the drug by week eight. The vast majority of the positive COVID-19 tests occurred after protocol (adherence) failure occurred, though the researchers fail to match cases to adherence levels. All major comorbidities (asthma, diabetes, hypertension, thyroid, family histories of diabetes or heart disease) were more common in the treatment group. Before we count such a study as "negative", we should like to see matching of COVID-19 cases to which participants adhered to the medicine. It is perfectly reasonable to perform analysis at a protocol level, of course, but when adherence is so poor, we need to understand the circumstances and results beyond what was reported in this particular paper. Perhaps that will be accomplished prior to publication.

In summary, the body of evidence on HCQ PrEP looks far more positive than the initial [naive] 75% positive rate suggests. In fact, it looks dramatically positive after examination of the weakness of the negative studies. With all that in mind, let's move on to the main event.

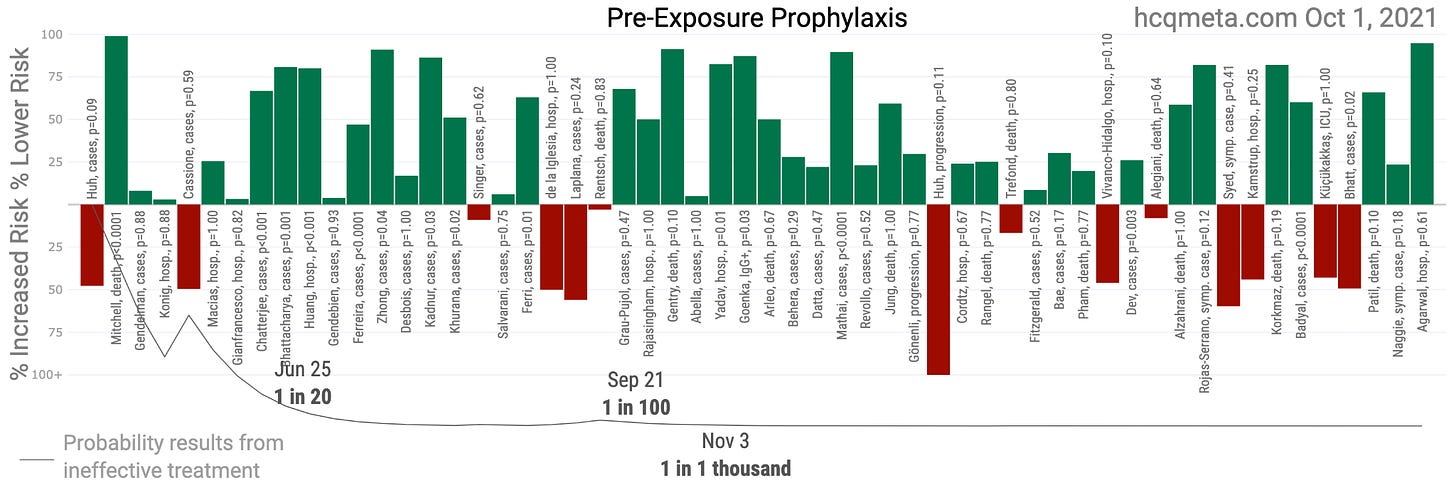

The Stricker and Fesler Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis focuses on HCQ PrEP studies on healthcare workers in India, a topic I have written about previously. The analysis is largely straight-forward, and includes 11 total studies (excluding the recent Bhatt preprint). Though I would personally liked to have also seen a chart on dosing quantity differences, what this meta-analysis shows is a temporal relationship to continued dosing with HCQ, a drug that can reach cardiotoxic levels (most often when consumed too quickly), and has a long half-life of several weeks in the bloodstream. Such a temporal relationship, consistent over all five studies where broken, is highly suggestive of antiviral action.

In total, the meta-analysis shows a 44% risk reduction of contracting COVID-19 among the 11 studies, but a whopping 75% risk reduction for those participants continuing to dose for at least six weeks. That's a fantastic result, and it is a great shame that it isn't getting more attention. If people are losing trust in public health, this is the kind of strange lack of attention to life saving medicine that stands out.

One of my specific frustrations with the HCQ debate has been the equal (or greater) treatment of evidence from studies on suboptimal protocols. It doesn't tell us anything much about the optimal use of HCQ to study what happens when we have critically ill patients snort it up their noses just prior to strapping into a ventilator. What we want to understand most is the result of the most practical version of optimal protocols. As such, we might even say that 75% case reduction is a lower bound on the possible effects of HCQ prophylaxis.

TrialSiteNews interviewed Dr. Stricker back in June discussing HCQ research and other topics.

Where is the Big American RCT?

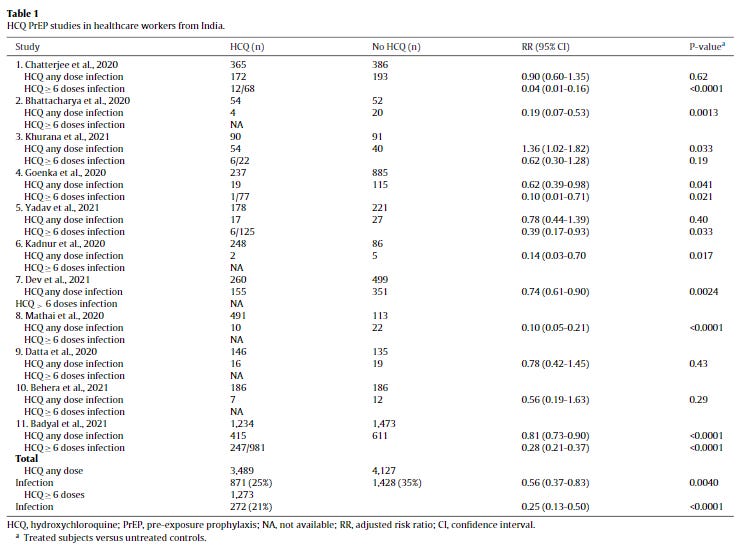

Well, that's a very good question. The HERO RCT (Naggie et al, 2021 preprint) seems to have been slowed due to recruiting problems in the aftermath of the heavy politicization of HCQ. The 23.5% risk reduction (29.3% after statistical adjustment), did not quite reach statistical significance (the study authors note that the study was underpowered) in isolation. The study only followed participants for 30 days---never reaching the six week mark where efficacy rates take off in the India studies. The risk reduction seems to still be growing at the end of the trial period, and was largest in older, higher risk patients, which is to say that the overall impact of such a protocol could in fact be much higher: perhaps in the ballpark of a net 50% reduction in cases, hospitalizations, and deaths. And even that number could grow after longer periods of PrEP dosing.

The trial author, Susanna Naggie defends the trial (not that such a defense should be necessary), in a video here.

The other major U.S. trial designed to test HCQ PrEP of which I am aware is the Crown Coronation Trial, run out of Washington University in St. Louis and funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. However, the HCQ arm of that 30,000 participant study was changed to exclude HCQ from the trial. Without politicization of the medicine during the pandemic, this trial would have been easily powered to achieve a definitive result. Still, the overall evidence in favor of HCQ PrEP looks quite solid, and ever better under the lens of optimal protocol hunting.

And we should group all the PrEP, PEP, and early treatment studies of HCQ together at the point at which we see temporal and dose dependent effects time and again. Such research should certainly be separated out, but at the point at which signs of antiviral action emerge so consistently, that observation ties the body of evidence together.

If you appreciate this review of the scientific literature to date, please subscribe to Rounding the Earth or share it with a friend. I am humbled and motivated to see RTE's reach grow to over 10,000 article views per day.

Exceptional work! Pointing out the obvious (12 irrelevant studies) was so impactful it has changed my perspective immediately! I was a Pfizer Pharmaceutical representative and know well how studies are used to manipulate narrative. Study dose has been used and abused to missinform. Ineffective small doses and known lethal doses have been used in published studies! Even highly renound NEJM AND Nature published and retracted terrible studies.

The question I always have about any Covid study is, With the pathetic inaccuracies in the PCR Covid test (up to 96% false positive) , how are any results meaningful? Thank you!

Btw, I am going to be supportive and subscribe. Voices like yours need support!

I think any of the concerns you have can be explained by the lack of grant funding for these studies. Also when doing research the person must be careful of career damage in choosing a particular reseach study and so if one uses small N and does T-Tests, it is still statistically first rate but doesn't SPLASH and POP the way huge numbers do when read by the masses and the govt.