"For every thousand hacking at the leaves of evil is one striking at the root." -Ralph Waldo Emerson

Articles from the Wars of the Matrix GANGs can be found here.

My (second) article on the Dalai Lama drew some heated conversation. It also drew multiple emails which might be amalgamated as, "We should all be revisiting our assumptions of history." Regardless of who does or doesn't agree with my primary perspective on a topic, I love the energy to look back, sweep some dust away, and dig at the roots. We will not find our way out of the Matrix without detaching ourselves from perspectives that we have made too much a part of our identities. Our epistemology cannot be healthy without the energy to explore what we have taken for granted.

The term “epistemology” comes from the Greek words “episteme” and “logos”. “Episteme” can be translated as “knowledge” or “understanding” or “acquaintance”, while “logos” can be translated as “account” or “argument” or “reason”. Just as each of these different translations captures some facet of the meaning of these Greek terms, so too does each translation capture a different facet of epistemology itself. Although the term “epistemology” is no more than a couple of centuries old, the field of epistemology is at least as old as any in philosophy.[1] In different parts of its extensive history, different facets of epistemology have attracted attention. Plato’s epistemology was an attempt to understand what it was to know, and how knowledge (unlike mere true opinion) is good for the knower. Locke’s epistemology was an attempt to understand the operations of human understanding, Kant’s epistemology was an attempt to understand the conditions of the possibility of human understanding, and Russell’s epistemology was an attempt to understand how modern science could be justified by appeal to sensory experience. Much recent work in formal epistemology is an attempt to understand how our degrees of confidence are rationally constrained by our evidence, and much recent work in feminist epistemology is an attempt to understand the ways in which interests affect our evidence, and affect our rational constraints more generally. In all these cases, epistemology seeks to understand one or another kind of cognitive success (or, correspondingly, cognitive failure). This entry surveys the varieties of cognitive success, and some recent efforts to understand some of those varieties.

Those who operate the Matrix do so—often with our unwitting permission—at our flawed epistemological roots. We can turn that around.

We should engage the quest of righting our epistemological processes lightheartedly, and forgive ourselves of our misinterpretations, often honestly acquired from corrupted sources. I suspect that most of us—even those of us who might be described as naturally or actively more skeptical than average—likely believed a number of false facts fed to us from almost any media—even history textbooks, and sometimes even first-hand experience. This is a world of powerful illusions. Toward the end of this article, I'm going to share some inspiration from my friend Dr. Madhava Setty with respect to how we might deconstruct some of the Matrix for each other.

A Tale of a Complex Illusion

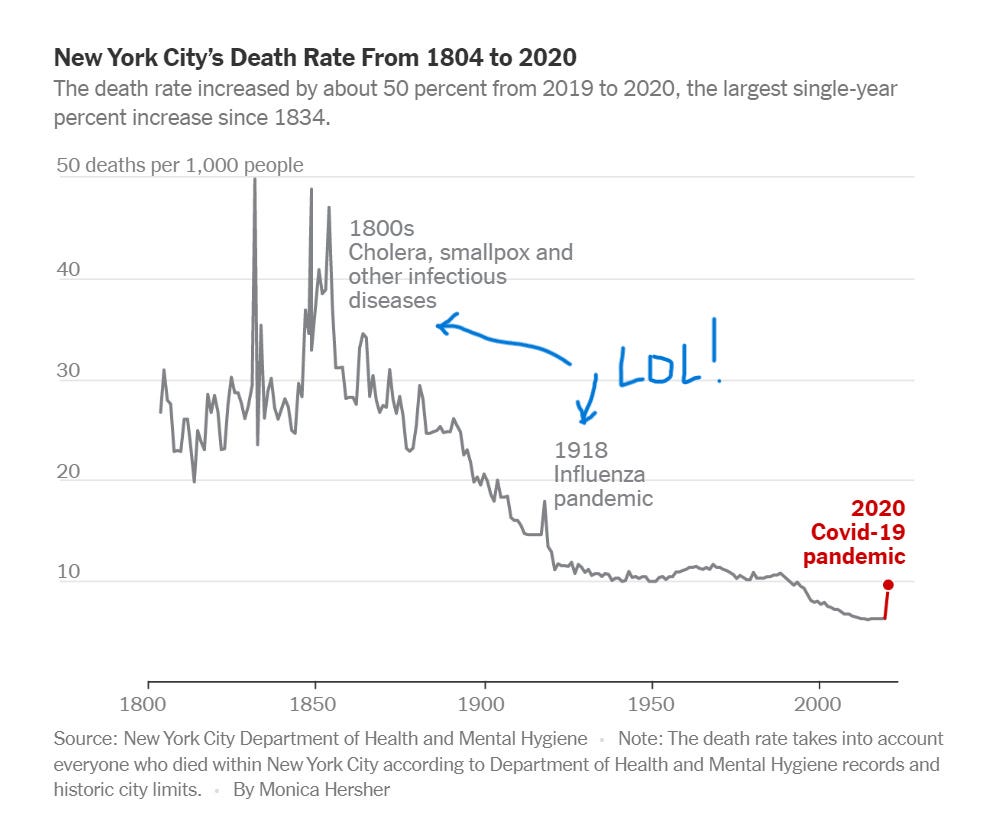

We cannot do this alone. During the plandemonium, numerous others have helped me see past some tales from the past that I had not the background or experience to even know to question. Just a few weeks ago, Mark Kulacz helped me recognize that the vast numbers of deaths I was taught resulted from the Spanish Flu were likely vastly trumped up through revisionist medical historians—likely by orders of magnitude. As Sasha Latypova points out, the 1918 "pandemic" looks like nothing more than a moderately bad respiratory virus season when we check the records. Somewhere along the way, a mythology was built around it.

There are a handful of illusions that I've identified myself, and that I can help other people recognize. Recall the Story of Daniel Tammet:

I saw a glitch in the Matrix. But not everyone could have seen this particular glitch. Perhaps a few thousand humans can perform the mental math feats Daniel credits to autistic superpowers. Perhaps only a small fraction of those people watched the documentary that I believe wove an illusion around Daniel. Perhaps only a fraction of those were ready with their critical eye.

See the problem?

Going deeper, it's…ahem…interesting that Simon Baron-Cohen, the scientist who performed Daniel's brain scans, has multiple theories of autism that completely dismiss links to vaccines and environmental toxins. And then Daniel goes around giving talks to parents of children with autism—a cruel prank if Daniel is not autistic, or if those children are not endowed with mitigating superpowers.

But every appearance sells books, I imagine.

Following the money and conflicts of interest yields so much fruit…

Glitches and Glitches and Glitches in the Matrix

Once you start looking for them, you find them everywhere.

The Matrix Operators are not nearly as sophisticated as you might think. Why? Because they don't need to be. They mostly need for people not to have the time left after slaving away to feed and clothe their families to have the additional time to learn how to check up on them. This is likely also the reason they view the public with little regard. It's not that the public is stupid, necessarily (or maybe all of us are, but only some portion of the time). But what we're talking about is a series of magic acts—a flood of magic acts, actually. That is to say that there is an asymmetric information problem, and we do not have time economics on our side. Even those who do, like Penn and Teller, do not quickly unravel new tricks every time.

Now, apply what we have learned to world events.

Now consider the following: do you know whether or not the videos we all saw from China in early 2020 were real? Many have decided that they were faked, or inappropriately chosen. I was one of those. But now I'm not sure that I wasn't fooled a second time. If Wuhan was the ground zero for an intentional release of a more concentrated pathogen than most of us experienced, maybe they were in fact real. At the very least, we should not allow ourselves to be re-fooled into a totally committed view without a serious epistemology to guide us.

We are flooded daily with new tricks. Does anyone really believe these women can both identify realistic descriptions of the Christian right and the Taliban—but can't think of a single contrasting variable? Glitch in the Matrix.

Criticize either the Christian right or the Taliban until your heart's content. Tell me there's no difference, and I'm going to tell some jokes at your expense. Or maybe just highlight you in an article. Sorry, not sorry.

Note: It is perfectly possible that this represents a second-order glitch in the Matrix. It is likely that these women were chosen to weave the Matrix after being first fooled themselves.

There is a Way Out

It begins with taking a truly hard skeptical approach to any information delivered to us by parasocial sources. That's easier to do when you've seen enough glitches in the Matrix. So, here's a spoon full of sugar…

It is amazing how many people have been fooled by the notion that the videos from the Stanford Research Institute demonstrated true psychic powers…even with the full knowledge that the primary agent in those videos was a professional magician.

Train Yourself on Humorous Absurdity

Watch this video in which the Stanford Research Institute tests Uri Geller and others for psychic powers. Ask yourself, "Could I direct a short film demonstrating all of the same results, but faked?"

Of course you can. Because it would look exactly the same.

Exactly the same.

Except for one difference: most people would never think to promote the video as evidence of anything because we all know that there would be no difference between a true display of psychic powers and a produced video of rigged "experiments".

Have Good Faith Conversations

I suspect that we are trained into thinking such conversations are difficult to have. Sometimes they are challenging, but there are plenty of people willing to challenge their priors or hear new information. My first podcast discussion was a great example. I felt it was highly productive.

More recently, Madhava Setty attended the World Vaccine Congress, and had great success talking with people.

Prior to understanding what exactly he had accomplished and had in mind for future engagement, he emailed me and some others suggesting an approach of engaging more people on the other side of the debates we are engaged in. I misunderstood his suggestion at first, but after talking with him about his experience at the World Vaccine Congress, I get it.

There were both researchers and members of the press in the audience who were open to Madhava's questions that politely poked at the narrative of "safe and effective" vaccines [as a given]. I can imagine that he was friendly in his engagements. And he found people at the World Vaccine Congress willing to explore the epistemological roots…until…Madhava identified what one might deem an "agent of the Matrix":

https://research-repository.uwa.edu.au/en/persons/katie-attwell

Whenever Madhava suggested open discussion, Katie Attwell was there to say, in so many words, "That's a bad idea."

Why would anyone—and Attwell in particular—want to squelch open discussion in science? Science is about asking questions to dig deeper, and forming a better understanding of the world through exploration and experimentation (and interpretation of the results) based on those questions. And it is the crowd that better handles all that than any one individual. None of us has the education and perspective to know it all (or anything close to that).

Attwell calls herself "an experienced vaccination social scientist", which should be enough for any scientist to take pause. Most scientists do not consider "social science" to be science, but recognize it as "social engineering". And while there are elements of science in any discipline, it is recognized that social scientists are goal-driven (usually toward ideology or financial reward), and not the exploratory minds that engage in what we usually think of as science.

I found an interesting video of Attwell advertising COVID-19 "vaccination" by garnering sympathy for her unrelated illness. She has a nice accent. But more concerning is that she "specializes in mandatory vaccination policy" as per her academic homepage, and she doesn't want people in medicine to talk with people who disagree with her.

So, here is how you begin to weaken the Matrix:

Relax so that you can take the emotion out of academic conversation.

Dispel the anxiety of those who try to tell you that the others aren't worth talking with. That's also part of the illusion, and the people discouraging you from communicating are Chaos Agents, whether or not they know it.

Be a (Socratic) question asker for at least a solid portion of every important conversation.

Get your ducks in a row regarding facts that you would like to share.

Humanize everyone in your mind. Ignore the often illusory social boundaries to engage with other human beings. They may just listen more often than you think.

Identify those whose job it is to disrupt the conversation, and reveal them. Or simply have conversations outside of their control. Eventually, their controlling nature will be plain to most people.

Tell me the tactics that you apply to dispel the Matrix.

Persuasion is more art than science: attempts primarily based on facts and figures are doomed to fail compared to clever appeals to emotion. Our Matrix Overlords are exceedingly gifted at amplifying fear, manipulating compassion, and ruthlessly shaming their opposition.

If a person interacts happily and frictionless with 99 people who believe and understand X, that person is likely to scoff and dismiss someone who understands Y. Despite that, Y people should persist is they know the X's are being played.