"The more political the topic, the less reliable is Wikipedia." -Mathew's Law

Find other Bitcoin Wars articles here.

Judging by the standard internet experience, you might think that the Cantillon Effect is an unimportant topic in economics. It's one of those terms that doesn't bring the corresponding Wikipedia entry to the top of the results when you enter it into a search engine such as Google or Brave. Even worse, Wikipedia no longer has an entry for the Cantillon Effect at all, making the topic an overly brief mention of the entry devoted to the [exceptionally] underrated French-Irish Economist Richard Cantillon. Economics textbooks spend so little time on the Cantillon Effect that I've rarely heard it explained well—even among educated people (exceptional economics minds in finance may "know better than" to talk about it above a whisper), yet it stands out in my eyes as the fulcrum between authoritarianism and liberty among economic forces.

So, what is the Cantillon Effect, and what is it that the institutional Economics discipline seeks to hide?

Let's take a monetary journey together. Just me and you. I want to make sure we have a solid foundation for this relationship. Or at least to know whether or not it floats atop the labor of a crowd of global peasants.

Printing Currency on Monetary Networks

"Your network is your net worth." -Porter Gale

Ultimately, money exists on a network. And by network, I mean a graph, as in graph theory, which is the mathematical field of "dots and sticks", or more technically, "combinatorial modeling with vertices (a.k.a. nodes) and edges". Here are some examples of (diagrams) graphs that I created for a course I used to teach. Maybe you can see why the five graphs on the bottom row represent the Platonic solids.

But monetary and financial networks are far larger than the relatively simple examples of graphs above. The networks we're going to talk about are larger than I care to draw. My hand would cramp before I could get around the entire Earth!

Each dot/vertex/node represents a place where some number of dollars can reside. Technically, such points are enumerable, but we might talk practically about obvious domains including the possession of an individual or location in a bank account. So, practically speaking, the dollar network is a network of billions upon billions of nodes.

Each node is associated with some number of dollars so that the sum of all those dollars is the dollar monetary supply. We could talk about debits and credits, too, but for the purpose of this article, we don't need to get any more complicated than imaging nonnegative numbers at each node.

Now, here's the weird part: one node is special among all others as it gets to create new dollars at will. Like poof. Then suddenly that node has more dollars while the number of dollars at all the other nodes remains the same. I like to call this magical node the Empire Node.

Poof!

Number Go Up!

Now, let us think for a moment about what happens when the currency unit numbers on the global monetary graph change. As a simple example, imagine what does and does not happen to the value of each unit if the number of units at each node (bank account, wallet, etc.) doubles.

The total utility of the money supply remains invariant.

Money can continue to be used, the same as before, as an intermediary of exchange.

Logically, the agents (owners of units of currency) of nodes cannot buy twice as much as they could before. In fact, twice as much of goods and services aren't even guaranteed to exist in the marketplace.

The value of each unit of currency is halved to match the fact that the total value of all the existing currency units remained invariant.

The price of each good and service doubles so that the same value in currency is received in exchange of a given good or service.

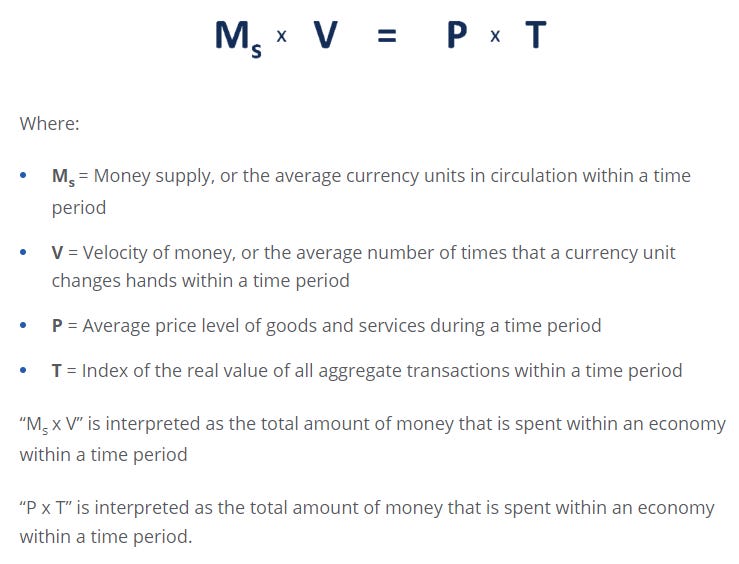

For simplicity, let us call this scenario an example of printing new currency. We'll tackle quibbles with the terminology in a bit. Now, I'll piggyback off the Corporate Finance Institute's presentation of the Equation of Exchange to justify my explanation of what does and does not happen when money gets printed:

It is often easiest to hold two (or just one) variable constant at a time when thinking through the Equation of Exchange. Holding V and T constant, we see that doubling M, the monetary supply, doubles P, the price levels. In the parlance of algebra, monetary supply and price vary jointly.

Now, let's change up the scenario. This isn't the whole story yet, but we're building up to it. Instead of doubling the units of currency at each node, imagine what happens if the entire money supply is again replicated, but the entire new supply (which doubles the total) of currency units gets deposited on the Empire Node (the way it really happens). In this case, the prices of goods and services once again all double. However, anyone who does not have access to the Empire Node suddenly finds themselves with half the purchasing power of their owned currency! In other words, they have had half their currency savings taxed. This is why the printing of money is often referred to as a hidden tax.

Some people simply call it theft. And the reason that Muneed Sikander, author of the article above, an advisor at the London School of Economics, refers to developing countries as getting taxed, will become clear as we continue our discussion. Terrifyingly, there are all sorts of people who defend the rhetorical notion that the creation of money is not the same as "printing money", but the point is not whether ink gets applied to special paper to create more cash, but whether or not the scalar (numerical value associated with the numeracy of dollars) at the Empire Node goes up. For the purpose of this article, we'll call the creation of money “printing”. The difference in economic effects is largely rhetorical, though there are some minor differences in the way money spreads out over networks (subgraphs of the whole network, sometimes separated by practical or regulatory barriers) according to whether it's locked in the financial system, or available as cash.

And the reasons for printing money are many:

Unelected bureaucrats want raises for not gossipping too much about the presidential candidate.

Paying the press not to talk about the Bush family's Nazi ties continues to cost a fortune.

Gotta reward the constituents with shovel ready projects.

The military industrial complex hired 1,700 new contractors.

Too Big to Fail Banks need another bailout.

Daddy needs a new pair of shoes.

Nancy Pelosi needs a new pair of shoes.

Note that interesting tidbit of trivia at the end: the City of London is not democratic, is not a part of the UK, and was never a part of the Eurozone (which explains why the euro never became the British currency), no matter what Wikipedia has to say about the matter. There are people who work in finance for decades who never find that out. Back to our primary programming…

The Cantillon Effect

"It's good to be the king." -Mel Brooks

Consider the monetary network (graph) to be a dynamical system in which currency units at each node move around the graph along its edges corresponding to the exchange of goods and services. If I pay you $50 for a bicycle at your garage sale, the node that represents my wallet loses 50 units while the node that represents your cash box gains 50 units. Every day, units of currency are added and subtracted from the totals that "belong" to nodes billions and billions of times. Money makes the Earth go 'round.

When new money gets created and "air dropped" onto the Empire Node, the controllers of that node gain in the power to purchase goods and services to the exact degree that everyone else loses. However, that's not a dynamical perspective. The truth is that exchanges of currency for goods and services take place over time, so time is the new dimension in our analysis of monetary network graphs, and that's what makes the system dynamical.

In the dynamical economic system, prices do not change instantly. Most humans do not understand the need to adjust prices until supply and demand signals land on them locally. Those signals propagate gradually through the market, starting when what we might call the Empire Node friends and family buy up goods and services in the marketplace. Those who are the first to experience those signals adjust their prices first, passing the signal on to their other financial relationships. The value accrued by the printing of money is strongest in the (graph-wise) neighborhood of the Empire Node, while the price is paid by those furthest from the core of the Empire.

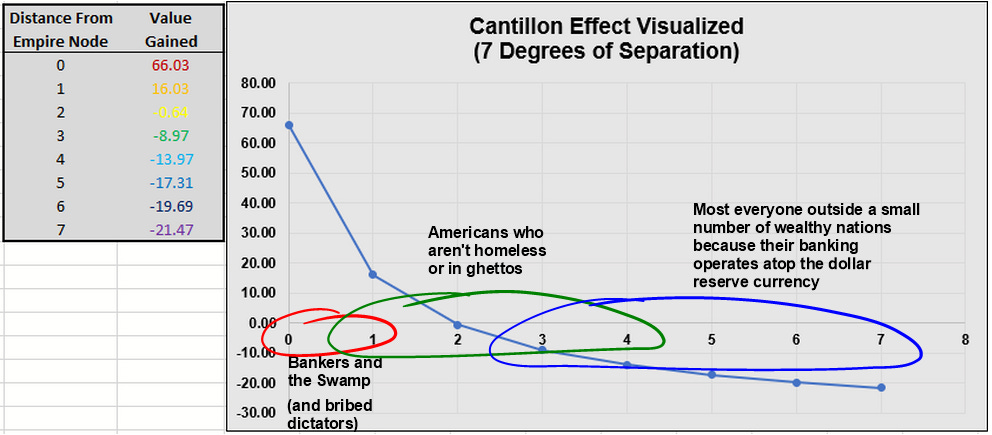

Here is a graph that I created to simulate the degrees of winning and losing from the printing of money by distributing the taxation effect equally across all classes of nodes (0 to 7 degrees) by shortest route from the Empire Node (call it a '7 degrees of separation' model) equally, while distributing the gains according to a simplistic power law. For the purpose of this exercise, focus on the generality of the system dynamics, and not whether I've done the several month study (or found one) that it would take to measure all this out (because I haven't).

Most of the value of the currency units created at the Empire Node accrues as actual purchasing power at the Empire Node. Some accrued in the vicinity of the Empire Node. Everyone else just gets taxed. Even worse, this tax gets sold to people as "just the way inflation works on consumer prices, bro."

Does it strike you how this process might advantage "the elite" (defined by short network distances from the core of the Monetary Empire) whether or not their education and experience amounts to economically benefiting the world commensurate with their remuneration? Automatic and unearned accumulation of wealth is a major byproduct of money printing, and this is what we call the Cantillon Effect.

A more formal definition from the SWF Institute looks like this:

A Cantillon effect is a change in relative prices resulting from a change in money supply. It is the uneven expansion of the amount of money.

Perhaps you can already see why a simple definition does not suffice to explain the Cantillon Effect. Note how the Cantillon Effect generates an artificial Pareto distribution (like an 80/20 rule) of success, holding all other variables (wisdom, education, effort, conscientiousness, cleverness, virtue, etc.) equal. Such results always exist, but not to the extremes that we experience today.

Note also how the American economy benefits from this system at the expense of the rest of the world. By virtue of being closer in economic relationship to the money printers, most Americans win, or lose small enough that regular doses of brainwashing and propaganda, along with the reality of not living in a penitentiary or the third world, keeps them in line. That or they discover opioids or meth.

This is what the U.S. [elites] really got out of Bretton Woods: the ability to shadow tax most of the world for decades and decades while centralizing power at home to stave off rivals. If that sounds like a system of modern quasi-slavery without the chains, you're getting it.

You may also be starting to understand why Satoshi Nakamoto felt Bitcoin is such a crucially important innovation.

How It Comes to an End

"Only he who has no use for the empire is fit to be entrusted with it." -Zhuangzi, The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu

I could quip, "Bitcoin fixes this," but that rushes past the point. Note how little incentive those near the ring of power have to achieve something in order to obtain wealth. The incentives of the children of one generation of elites involve whatever it takes to stay near or inside the Empire Node. Over the years and generations, they learn not how to foster technology and its associated values, but how to steer the gains of technology toward only themselves while sabotaging everyone else.

Inevitably, those people whom the Empire royals find revolting tend to revolt. A successful revolution requires finding the right chink in the armor to exploit, but it happens. It happens when the distance between the king and the subjects grows, economically speaking. And when the revolution begins, the Empire Node friends and family find themselves without the ability to even buy more allies. Dozens of nations around the world are studying how to switch onto the Bitcoin network. At the end of the Fall of the World Economic Forum Stooges, nobody will want Central Bank Digital Currencies (with new and improved surveillance features!), and the revolting masses will learn to raise their own militia, security, and police forces locally, and pay for it with a currency of fixed supply. Thanks for coming out.

If that wasn't enough, the Cantillon Effect has a time component in our dynamical model. The result is implicit generational warfare. Those benefiting from that system must con each new generation into accepting a starting position far from those who benefitted in years past. All costs to the riches of the Banking-Swamp-Oligarch circles ripple as costs through the system in a way that sloughs the costs off onto future generations, and even their own innumerable progeny. Not enough wealth can be passed down to cover all the costs. Everyone runs a Red Queen's race to remain in the neighborhood of the Empire Node, becoming lonelier with every step. Tensions rise and keep rising until Moloch begins to consume itself, as it has.

Eventually, the culture wars subside among those building their own system outside of the Kunlangeta's kingdom, after the true crazies impale themselves against whatever sharp objects they can find. More people will get over their mind viruses and start to recognize that,

The patriarchy is the monetary system.

The institutional racism is really the Cantillon Effect.

Not everyone who disagrees with the "facts" of Woke ideology is a bigot.

Only some subset of cops are bastards, and that radiates primarily from the organized criminal enterprises that feed off the excess wealth generated by the Cantillon Effect.

The real Alpha is the person who takes care of their community, not the dipshit politician on TV. That illusion was paid for by the Cantillon Effect.

Rape culture is primarily a feature of the Empire Node, enriched by the Cantillon Effect, or the madness of the ghettos, engineered by the Cantillon Effect.

Almost nobody cares to hate transgender people unless they're ruining sports, twerking in a public library, or demanding the right to lurk in the wrong bathrooms.

The people in the flyover states still have food.

Never trust an industry that profits off your misery rather than your health.

That's when a critical mass in America will manage to find the Bitcoin network—urged on by their cousins in Latin America, the Caribbean, South America, Africa, South and Southeast Asia, now the Australian continent, and potentially most everyone else. That's how the Kunlangeta lose the power of enslavement, and the Corporatist Empire finally falls.

And then there's nobody left to tell the king, consumed with the ambitions of Ozymandius, that he has no clothes, much less that the deer is a deer.

Why Richard Cantillon Was Brilliant

Where to start?!

Though born to a land-owner, being an Irishman in intellectual Europe did not exactly give a man a leg up in the 1700s. The Irish were considered inferior long before Charles Darwin's and Francis Galton's crowd declared, without much in the way of evidence, the Irish to be evolutionarily inferior potato eating person-rats (not a direct translation). But Cantillon rose through the ranks of academics and bankers with an inventiveness that deserves greater historical credit. Were it not for the terrible moral reputation of the economics community, and the inability to declare champions on the basis of proofs or even original thoughts, Cantillon might be remembered somewhat like the great mathematician Leonhard Euler whose accomplishments span essentially every active mathematical field of his day (not to mention the invention of graph theory). We might at least anoint Cantillon the Benjamin Franklin of his economic era, or carve his visage into Mount Satoshi (once we pick a good rock face to rename in honor of Satoshi Nakamoto).

Cantillon was ahead of his time, and his discussions of economics influenced many more well-known economists such as Adam Smith and Frederic Bastiat. Cantillon's original ideas, aside from the Cantillon effect, included,

The practical conception of entrepreneur as risk-bearer, taking on certain liabilities with the hope of achieving (technological) gains.

A fan of Sir Isaac Newton, Cantillon was among the very first economists capable with calculus, which surely related to numerous of his breakthroughs. Newton's influence may also be the reason why, as Economist Murray Rothbard pointed out, that Cantillon was virtually alone among economists of his day in his ability to isolate one among many variables in his thinking in order to best examine its economic effects. Thus, Cantillon helped raise economics to a discipline of studying dynamical systems with dynamical models.

The development of spatial economics, which continues to explode in importance.

While an investor in John Law's Mississippi Company, Cantillon bought low and sold high. Though he was pursued by lawsuits over his sales, his experience and observations contributed to the early understanding of economic bubbles.

Foundational work on the way that changes in the velocity of capital and total monetary supply affect market prices, which was codified only much later in history in the Equation of Exchange.

Cantillon set in motion numerous vectors of thought regarding Subjective Theory of Value, which recognizes group dynamics as the sum of the phenomena of the expressed values of individuals, rather than the other way around. This work influenced my thinking about the problems of Asymmetric technology.

Cantillon set in motion a lineage of economic thinkers who understood that the neighborhood of a market price was dictated by the forces of supply and demand.

Cantillon implicitly employed approaches similar to (Founder of the School of) Austrian Economist Charles Menger's methodological individualism.

However, Cantillon's work was quickly lost and forgotten until just one of his essays was dug up a century later, and recognized for its greatness by a group of discerning economists. His Essai Sur La Nature Du Commerce En Général is sometimes said to be the first complete treatise on economics (with additional scientific advances). It is sometimes debated as to whether or not he wrote more [still] lost works, but given the clear connections between Adam Smith's work and ideas that seem to have stemmed from Cantillon, we can be nearly certain that Cantillon's writing was multitudinous, and circulated among the greats of his era. While written in 1730, and published in French in 1755, Essai was never translated into English until 1932.

It may be that Cantillon's attitude toward publication was similar to that of the great mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss whose motto "Few, but ripe," indicated an attitude toward publishing only his polished gems, whereas volumes of mathematics sat idly in Gauss's personal notes, sometimes only to be discovered centuries later. It may also be the case that letters about economics written by Cantillon were unpopular among Europe's neo-slavers at the East India Companies, many of whom would have been among Cantillon's contemporaries.

It may very well be that Cantillon was never considered the founder of a school of economics as was Menger simply because the burgeoning era of Corporatism left little oxygen for the development of his thoughts into a movement. On the other hand, Menger stood opposed to the German school of economics that coincided with the Prussian education model, which aimed at subduing individual agency, and later the rise of the Nazi empire.

I’ve never formally investigated/learned economics, mostly because I’m philosophically opposed to the axiom set. Nonetheless, I’ve observed the Cantillon Effect. Having a name for it will certainly make it easier to discuss. Thanks for educating us!

I learned about this general concept reading about the Nationalist Chinese during the Japanese occupation of China. As a government-in-exile with little access to real goods, they indulged in the printing press. The result was a system where those closest to government would have their salary earmarked to the very latest inflation values and everyone else sunk deeper into poverty.

I guess the question for today though is what happens when the money spigot gets turned off after more than a decade of full blast. Last time they reined things in a bit it didn't go so well. So many of those close to the Empire Node that look like genius trading firm masters of the of the universe are in actuality just beneficiaries of this Cantillon Effect. They can't survive without it.

We haven't even considered the effects of money creation through credit here which I imagine amplifies this effect immensely. I also believe it will amplify the destructive effect of turning off the money spigot.