"There's a fine line between genius and insanity. I have erased this line." -Oscar Levant

This article has been in the works for months, but in actuality for years. I have written various smaller versions of it in numerous places ranging from my own Facebook to anonymous accounts (no, I'm not revealing those…It's nice to sometimes just be a mischievous cartoon animal aside from the cacophony of human politics). I was inspired to finish this article just today specifically after watching a presentation at Pandata by a self-described generalist who put together the immense and superb Massachusetts COVID data project.

As with most of my articles, I am publishing this one far too early. There are too many pieces of the Big Picture that need attention and I typically have a fraction of a day to devote to each of them. Today I was in nearly seven hours of meetings. So be it. Somehow, the Earth is revolving faster these days. It is downright unreasonable to expect a well-defined conclusion of a discussion about a complex problem. My imperfections are on display, but at least these thoughts might be useful to somebody. More now than ever, perfection is the enemy of the maybe-good-but-at-least-basically-sane.

Perhaps some Einstein can take this up and complete the Bigger Puzzle?

Or maybe the crowd is even wiser than any of us. I expect as much.

A Brief Confession

"Genius is the recovery of childhood at will." -Arthur Rimbaud

Confession: I hate calling myself a statistician. I do so because (1) I do enjoy discrete math, and even where I forget terminology and formulas, I spent enough time with it all that I can look them up or derive them; and (2) having worked my way through college doing actuarial work (10/10 on the first two exams in the casualty actuary track), worked as a quant-trader on Wall Street, and spent productive time in corners of worthwhile places that include the Human Genome Project (not my greatest contribution, but the one with instant name recognition), that's the easiest way to explain myself on the most general sort of resume. I also enjoy teaching combinatorics, probability, and statistics. I tutored a few people successfully through their graduate level statistics courses, including my wife who is now a well-published Biochemist and Bioinformatics instructor. The description of Statistician also fits with my having written some math books, a few dozen commercial math courses, put together the Tyson/Fareed analysis (and chapter in their book), and worked consulting jobs of a variety that involved data analysis in productive projects. But most of my serious studies of math came during a three-year stretch of my life as a preteen and teenager when I was building the most obvious skill set that I could in order to escape a dismal captivity that I refused to live with.

If I'm not a statistician, what am I?

A person. Like you.

Or more of a punk, really. Growing up I spent many times the number of hours around people whose job titles included drug dealer (my four brothers), stripper (a few of their girlfriends), or lobbyist (two uncles) than around "respectable people" outside of school (which I skipped as often as possible without risking graduation).

And I love existing and existence. This being alive stuff is just…amazing. Definitely better than the alternative. Just going for a walk through the nature preserve near home feels better than laying down in darkness. That feels like a clue without scratching the surface of life's myriad adventures. I'm 44 years old and I feel like I've only learned about the tip of the tip of the tip of the iceberg of this great big existence thing. It's sometimes frightening and painful, but so often fascinating and beautiful. And it's full of observers who get to observe each other in a big freaky social dance, and I even love observing the observers. Is there a vocation for thinking about and promoting everything fascinating and beautiful, making use of some of it along the way? That's what I'd like to be when I grow up.

Where are All the Geniuses?

"Everyone is a genius at least once a year. The real geniuses simply have their bright ideas closer together." -Georg Christoph Lichtenberg

A couple of months ago I was made aware of an interesting article suggesting that we stopped making Einsteins. From that article,

I think the most depressing fact about humanity is that during the 2000s most of the world was handed essentially free access to the entirety of knowledge and that didn’t trigger a golden age.

I don't want to bash the article, which is an exploration of the absence of people who fit some set of criteria? I get why the author walks down this path, but I'm going to argue that (1) this statement is strictly false, and (2) it's the wrong path. I do get why it seems like something is missing in the sauce of human greatness. But we first need to better explore the question as to what exactly we're missing.

We're asking the wrong question(s) about education and greatness. We turn greatness into something mythological that can only be achieved according to the judgment of promoters who write the news and history. The notion that all the heavy lifting of society building is done by a few Einsteins completely ignores the complex interplay of all the members of the tribe (not to mention most of the real accomplishments of society, which includes such mundane tales as vegetable gardening and child rearing). Sadly, we live in an era in which most of the tribe is brutally hacked, so there is less achievement than there would otherwise be. Even worse, most of that achievement is accrued by people who are hungry for rewards, not hungry to create. The pathological hacking of the tribes drags down everyone, and in ways we can barely comprehend on a daily basis. We are left thinking of a famous few brains as the Geniuses because they are so anointed by people who want to sell us postcards from History. But to square the circle simply, the brain is not the body.

And if you want to be the brain that hovers without the body, you're the problem. Even worse, there are institutions set up to sell you your impossible quest. It ain't cheap, either. That's emotional dependence. That's extended childhood. And to justify the price tag, it's sold to everyone who desires status, or enough income to do a bit more than just raise their family on.

Fun fact 1: The average annualized earnings of a participant in the U.S. labor force (of just over 127 million individuals) was $191,728 during the first quarter of 2022. Earning that amount would put you in the top 5% of American earners.

I'm going to argue that there are far more supergeniuses than ever before (though there certainly are by metrics that relate to technical skills or earning potentials), but that there are reasons why you're not hearing about them. I'll tell you about two of them in particular whom I taught at the two education centers I built in Alabama and Texas.

Fun fact 2: In 2007, I built an education center just south of Birmingham, Alabama on a $16,000 budget while living off $1,000 a month for the first two years. Eight of the first 100 graduates attended MIT. Six of the first 150 were Presidential scholars.

A few months after I built a school in Alabama, a mother from an hour north of my center called me up one day and told me about her daughter who joined the math team and was beating not just all the kids in her small schools division, but all the kids in the large schools division as well. The kid just loved working problems, and she was about to give up studying as a prima ballerina to throw herself into deeper studies. She wasn't challenged at her small town Central Alabama junior high school, so her mother was willing to drive this girl two one-hour round trips for two hours of class twice a week to take two classes in my programs (that's 8+ hours a week of sacrificed time by mom, if I explained it correctly). Algebra, Geometry, Algebra II, Number Theory, Combinatorics/Probability/Stats, Graph Theory, Complex Geometry…

This child worked on math for hours every day, and then in the ninth grade decided to also drive to Birmingham and back to attend the math magnet program at the Alabama School of Fine Arts, and then continue taking two classes a week (most advanced students took one nearly all the time) with me before driving home. After two years, she exhausted the programs there while continuing to dominate math team, but also programming and robotics. So, she took the leap to maybe the most famous private school in the world: Exeter. For those who don't know: Harvard is the Exeter of the University educational tier, except with slightly poorer (median wealth) families.

Two years later she graduated as the valedictorian of Exeter having qualified for a national Math Olympiad and won an Economics competition at Harvard. Off to MIT. Nearly perfect grades and honors. Then into the artificial intelligence industry for four years. At the age of 27 she took a job at Thiel Capital. You don't know her name (save for the handful of her classmates reading this). With some work, you could probably find it out. But her breadth of knowledge in her technical studies could not have been matched by those much earlier because some of what she studied hadn't been invented yet. Will her name ever be broadly known?

Does it matter?

Maybe only to those in need of resurrecting and expanding some mythical Mount Olympus.

After I moved to Dallas where I built another school in 2013, I was introduced to a surprisingly emotionally normal nine-year-old boy who had already aced a college course in Modern Algebra (not a watered down version—I met the professor). During the time I worked with him, he became the first elementary schooler to achieve a perfect paper on the second round of the American Mathematics Competitions. I know how hard that is because in the 90s I became the first underclassman to do it, and that was my third straight year of working problems eight hours a day for most of the year. A fifth grader had now accomplished what was previously nearly impossible to anyone younger than 16 or 17 years old.

How difficult is that?

Here is from an essay I wrote on quora:

The AIME is hard enough that, on average, these exceptional students correctly solve 5 out of 15 problems over 3 hours of work.

Let that sink in.

Around 4% of those students qualify for the Olympiads (USAMO or USAJMO).

That’s 500 out of around 16,000,000, which is 1 out of 32,000 or

0.003%, give or take.

For comparison, 0.27% or so of people have IQs of 145 or above.

Again, the self-selection for taking these exams is not perfect, but we should expect for around (at least) 99% of students with IQs or 145 or above to fail to qualify for a national Olympiad.

Add to that the fact that a few singularly gifted students qualify for the national Math Olympiads 5, 6, 7 or more times, and you get a picture of an exceptionally challenging mountain to climb. In fact, it might be said that 10,000 or so adult Americans were likely to have achieved such a feat as a teenager if everyone had had the opportunity. Around 8,000 people worldwide have climbed Mt. Everest, and I’ll guess that includes somewhere around 2,000 Americans. But the number of Americans who even consider that challenge is small. Why risk it? It may be reasonable to suggest that far more than 10,000 or so adult Americans are/were likely to actually summit Mt. Everest.

In other words, the AIME is hard enough that scoring the 10+ correct answers out of 15 usually necessary to qualify for the USA(J)MO is a greater challenge for a high school student than climbing Mt. Everest is for an adult.

He has since won three middle school national competitions (only student to high-score that test three times), and won three gold medals at the International Mathematical Olympiad (IMO). There will likely soon be a fourth gold medal in a few weeks, and there might have been five, six, or seven had he not had to compete with the U.S. team members who have won most of the international competitions over the past few years. Only one student has ever won more than four gold medals (not from the U.S.). I am in position to speculate because even when he was ten, I had to spend four hours each week sifting through problems to work with him for two hours at a time. After the easier problems at the IMO, even a professional mathematician usually needs to stretch their creativity to reach a teachable understanding of the solution-hunting process unless they make mathematical problem solving their primary life's focus (which I do not).

Has anyone ever known that much math at his age?

Who knows, but the number who have can likely be counted on one hand.

Will he become a famous Einstein-ish mathematician?

Wrong question. He's a teenager. Hopefully he will do whatever fulfills him the most, and hopefully nobody pigeonholes him so that he feels free to hop into whatever discipline he likes. It's not anyone's business whether he becomes the next great mathematician or physicist, plays the cello for a living, focuses on raising a large family more than research, or crafts educational computer games. That's his business.

Maybe he'll invent something new and useful, make $20 million, then go globe trotting until he falls in love with some other country where he puts down stakes and builds a university to educate the next generation in relative anonymity. There are a trillion possibilities, and the ones he chooses are his business.

And who is to say that the most brilliantly creative person (who might be worthy of an Einsteinian label) won't be somebody doing something we don't even have a name for, yet? And why would raising an amazing set of twelve kids (should that turn out to be his preference) be any less valuable to the world than solving some problem 99.99% of the world has never heard of and 99.9% of those who have cannot understand?

I'm not saying there isn't an answer to that question, but that it's not anyone's place to answer it for another. It's not even anyone's place to suggest which options are more valuable for society, even if that were appropriate to project. But I will say that N billion people answering the question (as if a vocationally uniform answer exists) from armchairs threatens all human progress, but we'll get to why that could be.

Having taught motivated students online and in person from many countries around the world, I could go on with more stories. I couldn't tell you whether these are the two smartest students I've worked with. I wouldn't even know how to define what that even means. I root for (all of) them to live healthy, fulfilling lives. Mount Olympus can fend for itself. If they do not have the emotional space of their own outside of society's mental space in order to grow up healthy, nothing good will come of it. If they do not learn agency while developing their own identities, none of that matters. Even worse, the grotesque twisting of the tension of artificial mythology will continue to shape into culture wars and other destructive phenomena.

The Absurdity of Overspecialization

"Any intelligent fool can make things bigger and more complex… It takes a touch of genius – and a lot of courage to move in the opposite direction." -Ernst. F. Schumacher

I suspect that we are at the tail end of an era that demanded specialization in the sense of monopolizing one's time primarily in one field, which is itself defined by unwritten rules of terf. A handful of heroes escaped that route and still achieved notoriety, but economics both strongly encouraged demanding competition and paths toward application of skill that might never be well known to the general population. And remember the obvious connection between wealth and health.

Who is to say that there isn't some Einstein-level intellect sitting at a desk at the NSA or DoD coming up with new ways to spy on all the dirty anti-vaxxers?

That's not what an Einstein would do?

Is that due to intellect, or mythology?

How did Zeus treat the sheep, again?

Do we even know what the actual Einstein would do in every environment? I don't.

Do we even know if Einstein is a genius in every environment? I'm sure he's quite bright in a wide array of universes (circumstances), but I truly have no idea.

Why the Einstein fetish, anyhow?

Are we asking the most important questions? Or is the stable advancement of the tribe the primary goal we've been hypnotized to ignore? Maybe we're not fully understanding how the underlying issue is economic, and that we're ignoring the obvious questions on that front. In order to begin brainstorming on what economic questions we even need to ask, I've created a diagram to represent the economic order of vocational and bureaucratic specialization.

Sorry if I missed some of you. I know that Gauss proved that there are 17 professional pie slices that can be constructed with a ruler and compass, but I get bored easily.

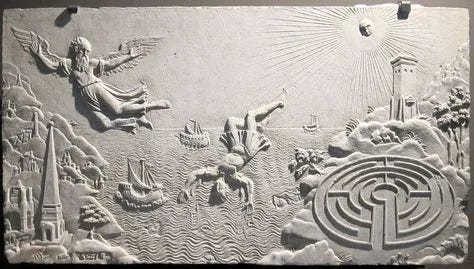

Kidding aside, what we're looking at is something like the body Moloch, a topic that I wish I'd had more time to write about. Our economy, which is a marvel of nature, and representative of the collective will of humanity, has become a Molochian maze so large and overly complex that entering the labyrinth to go to work as a specialist means losing all sense of self—and any view of the Big Picture.

Where am I? Who am I?

What would I even be if I left?

The nature of the maze is that everyone sees the twists and turns (corruption) in their own zone, but the vision of each specialist is limited by the bureaucratic form of Gell-Mann amnesia.

If you can't leave the labyrinth, you're not a mythological genius—you're the minotard. If you spend your genius to build the labyrinth wider to accommodate your own terf, then later try to escape, you risk your children's survival on their own maturity. A sacrifice to Moloch.

No matter how smart you might be. You begin to defend your position in the hierarchy not by producing better (because you no longer know what makes the machine function better—you just have signals from other lost souls in the maze whose corruption levels you cannot surmise by definition of your different specializations).

Where are all the Einsteins?

Most of those with such creative potential are trapped in a Catch-22 of their own tailor made design.

I don't mean to make it sound like I have all the answers here. Much of the point is that the complete set of answers is something like a reorganization of the maze in which the whole tribe participates. We need to allow for the powerful forces of emergent organization, and that involves the whole tribe, from the ground up. The Acolytes of Einstein need to get out of the damn way—not just in public health as is apparent daily—but in totality. The quest for the next mythological god to save the materialist moment feeds the Kunlangeta whose top-down organization of the maze results only in the codification of their own flawed images.

Source: "Watchmen": The One Thing Nobody Says about Adrian Veidt aka Ozymandias?

The giant squid is actually a symbol of how insane and out of touch with humanity Adrian Veidt is. He had been aloof and emotionally detached from people all his life, observing and calculating them from above. It takes insanity and detachment to turn three million victims into a statistic to shock the US and Soviet governments into declaring world peace. When Zack Snyder got rid of the alien squid in the movie because he thought it was cheesy, he missed the point. The giant squid was supposed to be cheesy and absurd because it was a symbol of how nuts Veidt is. He took on the weight of saving the world in the most horrendous way possible because he thought it was necessary. Because he's a flaming lunatic.

He is proof of the thesis that a crazy clever person is incredibly dangerous. Because he thinks he's doing the right thing.

You want for the smartest man in the world to be a genocidal lunatic? Just keep chasing Ozymandius Einstein.

Fun fact 3: I named my Dallas school Daedalus Education.

Fun Fact 4: The artist of my school's logo, above, graduated from medical school disgusted by the system. He became an artist and wrote what stands out as one of the most prescient books about American medicine prior to the plandemonium.

The Tiger-Powered Feedback Loop

"I'm a misunderstood genius."

"What's misunderstood?"

"Nobody thinks I'm a genius."

-Bill Watterson

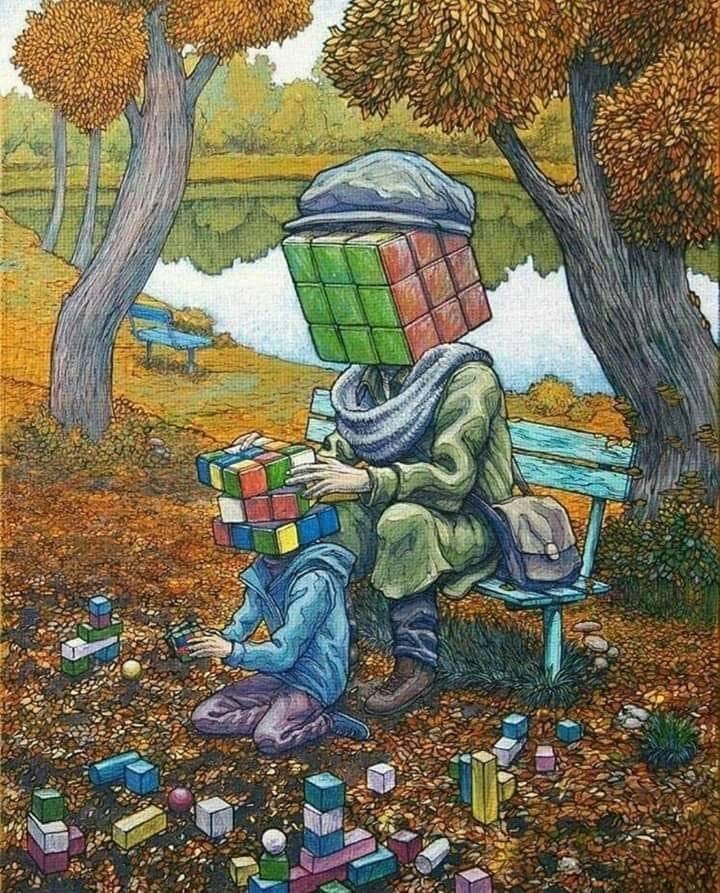

Right now, the greatest geniuses in the world are anyone managing to raise healthy kids in this environment.

Credit: Sensei spreading knowledge to young by Chris Baradaran

The American bastardization of Dr. Maria Montessori's educational system is one of the most emblematic signs of the times. For an additional $10k to $20k or beyond in some cities, wealthy families can send their kids to "Montessori schools" where their children will enjoy a clean upscale learning environment free of poor people. The greater personal attention to each child, Socratic conversation, and manipulatives are all surely upgrades from the standard education model. The problem is that it all completely misses the primary point of Dr. Montessori's mission.

When Dr. Montessori looked out her window in her little corner of Italy, she recognized that the visible problems on the streets—society's ills including crime and generally unhealthy people—were unnecessary. She began teaching…not the wealthy kids, but the mentally unhealthy and the poor kids whom she recognized as likely to often grow up to become the chronic poor or even criminals. She taught laboratory science to children condemned to an asylum, and was extended an honored invitation to "raise" Rome's destitute children. And at times she taught all kinds of children together, but one way or another, no child was left behind in her system. In essential ways, her methods overlapped with Benjamin Bloom's experiments, with proof of efficacy across wide demographics. And yet what we get out of all that are a few little schoolrooms dotting the landscape of America's upper middle class neighborhoods where future Mandarins are raised.

Our community leaders aren't enacting "No Child Left Behind". They are enabling the fracturing of societal fabric.

For several generations, specialists have often passed their knowledge and talents down through family lines, resulting in deeper and deeper specialization. Many of them routinely voted in ways that sabotaged the education of anyone else who might compete. Specialized tasks require learning enough twists and turns that it's hardly possible to leap from an ordinary childhood to specialization without all the extra help. Many specialists of generations past spent countless hours in their 20s, 30s, and 40s reaching those plateaus. Now, with Khan Academy, a few additional AP courses, and the sacrifice of all playdates, every child (who isn't left behind by the lack of at least one specialist parent and at least one tiger parent) can achieve that goal by the age of 26.7 without ever getting to know any of the other children in the neighborhood where they grew up. Since being Einstein isn't in the cards, this really is the primary path toward being named one of the 30 Under 30, which must surely be something like the next best thing. You don't need to be the first person to understand the photoelectric effect in order to benefit from that photoshoot.

https://www.forbes.com/30-under-30/2022/

Not pictured: Satoshi Nakamoto

Given that the highest quality of college education now costs 14,712 years of a median pre-bachelors-degree American income (and you can thank Putin for that), entrepreneurial all-stars and academics are no longer allowed to think unapproved thoughts (which certainly limits new discoveries), and the new patent clerking is "all bullshit jobs" that require kissing some geezer's ring. But I know what every Tiger parent is thinking, "How can my child be almost Einstein if they aren't surrounded by all the almost-Einsteins?"

To all the parents: Take a deep breath and come to grips with an understanding that sifting for Einsteins as a first principle looks a lot less interesting, and maybe even bat-CoV crazy when you zoom out.

Source: 5 hidden facts about Where's Waldo

I'm not here to shit all over whoever is in those 30 Under 30 photos. I don't know them. Some of them may be doing things that are valuable in most any imaginable future context. Good for them. Some of them might be there precisely because they've dodged the repeated application of the many social poisons. Dear God, I pray that is the truth. But I've seen too much of the sausage factory, and I know that the paths dictated by the selection criteria are fraught with so many sick incentives that I worry for each of them, and I worry more for each of the rest of us. And for the all of us.

I also know that we shouldn't count on them to save the world. Reformulating the great mass of humanity will be up to all of humanity. It will be up to people whose interests are simply feeding their family more than it will be up to somebody who checks the post-Ivy League fame checkboxes. It will be up to the unsexy maintainers of the sewers as much as the heli-drone builders. It will be up to new networks not codified by the bureaucratic maze enthusiasts, whose children have not been wed to Moloch.

The future belongs to the people who can stand apart from it all, and do the work to untangle the labyrinth map. Now the generalists must be heroes.

We will still need some specialists. We always need a few of them, defined by some more natural dedication to a defined discipline. And because they are well rewarded, the incentive systems are hard to balance without tempting the worshipers of false idols (meaning no disrespect to Einstein). We have far too many specialists, so most of those so trained become the entitled Mandarins. We are all under strain from their gravity. And because we live under a regime of such vast corruption, it's harder to relax and refuse to play their games. The system needs to change, and our educational motifs are a critical part of the feedback loop. Plan to lead children with love, learn what can be done, and the rest…well, that's still a lot of work, too. But at least we'll have company.

When It All Breaks Down, Who's Going to Rebuild It?

Okay friends, I'm wrapping this one up now. I told you it was too soon. I told you it was imperfect. But I think I'm right that waiting for perfection would be waiting too long. I reserve the right to rewrite all of this as inspiration hits. This is all too important to leave in place. This is far too important not to discuss. This is for the children who may build the next Age of Enlightenment.

I doubt there's a better piece on the internet today. Or many days. Thank you. This is incredible.

Step one for raising healthy kids: throw out your TV. But everyone here knows that. Step two: either homeschool or find a SMALL school aligned with your values. Small is important because of the Dunbar number issue Mathew brings up in the linked post. I had sensed that intuitively but thanks for articulating it! Step three: live and model the fact that we are in this world but not of this world. Doesn't have to be religious but I suspect that most/all based parents model a values system that is explicitly "outside the labyrinth." Healthy kids WILL be outsiders in this society, because the society is sick. So I think it's best to get them used to being outsiders from a young age.