"Habit is stronger than reason." -George Sanayana

Consider this a modest beginning to a lofty series.

There was a lot of dirty data published at the outset of the plandemonium. This is true both in the sense that some of it is either conclusively or likely fake, and also in the sense that a lot of researchers were rushing out any signal they could establish just to get some puzzle pieces onto the table. After all, somebody didn't want for us to get much of a glimpse of the box cover, so we had very little idea of what we were dealing with.

Are these even all pieces of the same puzzle?

The Dirty Smokers Hypothesis

Early during the pandemic, one of the shock findings by researchers was that smokers seemed more immune to SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Say what?

Yeah, that's what we all said.

Pretty freakin' novel!

You're telling me! In one study (Israel et al, 2020), smokers were only around half as likely as others to get infected by SARS-CoV-2. While early data with counterintuitive conclusions should be viewed with a more skeptical eye ("Is there a smoker's paradox in COVID-19?" Usman et al, 2020), confirmatory evidence continued to roll in. In a living rapid review (Simons et al, 2021), researchers found current smokers to be at substantially lower risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection across several data sets.

While it is possible that smoking or vaping results in something like an overactive mucosal response that shields against a highly aerosol virus, there is a plausible biochemical mechanism by which smoking and vaping could protect people from COVID. Researchers have found reasons to think that nicotine could disrupt the spike glycoprotein interaction with some receptors functional to the infection process (Farsalinos et al, 2020).

In the June 10, 2020 edition of Journal of Inflammation (one of my favorite issues, if I may), researcher Gagandeep Kaur and colleagues published a study (Kaur et al, 2020) suggesting the intuitive likelihood that inflammation and degeneration from smoking/vaping does exacerbate COVID-19.

In this mini-review, we present the evidences that tobacco smoking and/or vaping e-cigarettes could weaken the lungs defenses, thus rendering the individuals more susceptible towards COVID-19 infection with augmented symptoms.

Further research, evidence, and commentary:

Current smoking is not associated with COVID-19 (Rossato et al, 2020)

Smokers who contract COVID-19 are twice as likely to be hospitalized (Hopkinson et al, 2021)

Broad internet search…there's a lot and there is some…I'll call it "inconclusive consistency" of the "smoker's paradox" with counterevidence.

While it is certainly plausible that smoking/vaping could provide (short term?) protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection, but suffer worse illness, let us keep an open mind about interpretations of these results for the moment…

Justifying the Squared Circle: Earlier Circulation of SARS-CoV-[X]

I use SARS-CoV-[X] here simply because I am not yet settled on a firm opinion with respect to whether the Wuhan strain, a slightly prior SARS-CoV-2 strain, or SARS-Omicron circulated first. But I'm fairly certain that at least one of them was infecting people on multiple continents far earlier in 2019 (or earlier) than the Wuhan emergence theories would allow.

A few months after I wrote that article, I connected with Rossana Segreto on Twitter. She had just completed an analysis of the mysterious 2019 VAPI/EVALI illness that was attributed only to vapers.

Quoting myself:

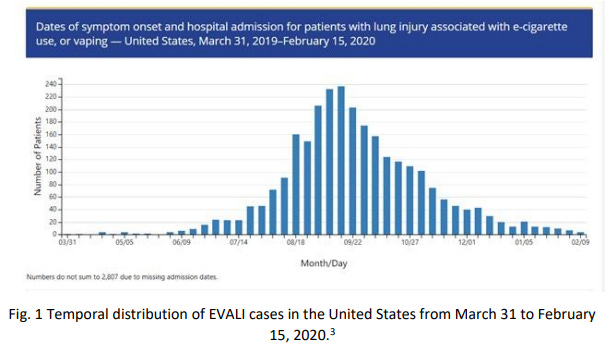

A number of people died of EVALI in 2019, and in fact, the hospital admission curve looks like an ordinary viral infection curve, which is not what you expect of an inhalation product, and is off-season for English boarding schools:

Now, I'll ask the question I've been wondering about: is it possible that more smokers were getting infected by SARS-CoV-[X] through 2019, thus conferring more natural immunity (and survivorship bias)?

Before I dive into that question, I want to mention a thought I've been having over the past several weeks. Recall how the repo markets freaked out in mid-September, 2019.

Is it possible that was the moment that one of the big banks caught wind of plandemonium, then began backing off offers in the repo market, triggering a race to the bottom?

Huh.

Is that why the three largest banks were bribed given $4.5T to play with during the plandemonium? Was that a pay off for remaining cool while the world was set on fire?

Huh.

A Grand Unified Quasi-Theory

So far, we have several interesting pieces of evidence that seem either unrelated or contradictory in nature. But I will suggest that this contradiction is a combination of bias and illusion.

The plandemonium might have started with a leaked/released SARS-CoV-[X] virus (or more than one, possibly) that was already infecting people perhaps as far back as 2017, but at least as far back as early 2019. Further, it might very well be the case that SARS-CoV-[X] was a minority part of the quasispecies coronavirus swarm?

If you're not familiar with the idea of a quasispecies (a.k.a. "swarm"), you can sift through an internet search, of course. But I'll try to explain the idea intuitively.

Imagine that your body contains some huge number of viruses, and that furthermore, some of those viruses are coronaviruses.

Source: Orkin.com

Since virions are hard to see even if you squint and use an extremely powerful microscope, maybe a furious swarm of termites helps visualize the idea.

Do all the termites have the same DNA?

Correct question! Five points to Hufflepuff.

As for an RNA coronavirus, let us begin with the crazy assumption that they do. If they don't, just fast forward in the story. Oops, now they already don't. While you were reading the first sentences in this paragraph, new virions emerged from the swarm with mutations. After all, every replicating genetic strand has some sort of mutation frequency and rate, and there are gazillions of them (I counted) hijacking cellular machinery for the purpose of generating little baby virions (actually, they're born fully grown, minus practiced manners). Furthermore, these mutations do not happen in the same places, so several sentences into this paragraph, we have a viral "swarm" with little differences among the members of the swarm that may be located essentially all over the genome (some mutations might be catastrophic, so the virions might not be viable, but you get what I'm saying).

The virions are alike enough that they function similarly. We might transmit that viral swarm around [the entire globe] and other swarms might be transmitted to us. We might wind up with two swarms that diverged enough to classify a bit differently, but they might play well enough together in the same hosts that we might just call the viral swarm a quasispecies.

Now, consider the following possibility: SARS-CoV-[X] escapes or gets released into human populations sometime in 2017. At first, the SARS-CoV-[X] virions might be a minority part of the swarm of coronaviruses, like hitching a ride in the back of a truck full of termites. Or people.

At first, all of them wear blue jackets and red hats, but a few of them mutate to have bandanas, maybe stripes, bad hair cuts, or whatever. But you're wearing a green shirt and have a spikey hairdo.

While you might be aerosol, there aren't enough of you to infect people, so for a while you have to reproduce within the swarm until one day there are enough of you (your near-species subswarm) that you begin to cause infections. Maybe this becomes noticeable in early 2018, and it even happens in some white tailed-deer, minks, and quokkas.

Quokkas?

Still with me? Good.

Through 2018, SARS-CoV-[X] bounces around, infecting a few million people around the globe. But that's a tiny number when you think about it, and only a few tens of thousands might suffer serious illness that could be chalked up to "viral pneumonia" or the like.

By 2019 the cases might be piling up, but perhaps smokers and vapers were more susceptible due to generally more inflamed pathways and the tendency to huddle together every 75 minutes in superspreader events. Then, by late 2019 when the pandemic is really getting going, the smokers and tokers who survived the "VAPI/EVALI" illness are more likely to have antibodies, giving them natural immunity to infection. So, they have lower rates of illness in 2020, but still higher rates of severity as one might expect.

Thus, we have a functional early leak or release theory that is fully consistent with all of the crazy data.

And on that note, I hope you have a wonderful day thinking about quokkas and other good things. And maybe subscribe to Rounding the Earth to support this sometimes educational content.

This makes a whole lot of sense to my smooth brain.

Would be interested your thoughts on Geert's interview on most recent Highwire.

If I had an income there are many excellent substackers I would happily pay for, you being at the very top.

Very interesting theory! I recently attended an event with several of the "freedom doctors" during which one of them mentioned something about smokers possibly being less vulnerable to infection (although still vulnerable and still at risk for serious complications) because the nicotinic receptors are already occupied.... Pardon, I'm not a biologist and likely fumbling the terminology, but I believe it was that these receptors were, like ACE2, amenable to the virus receptor binding domain, so having niccotine in the bloodstream could be protective - at least for those sites.