Why Would Silicon Valley be Ground Zero for Banking Centralization? Part 2

The Monetary Wars: Part 17

Check here for other articles on the Monetary Wars.

As of this writing, HSBC has just taken over the UK arm of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB).

Hunt wrote on Twitter at 7am: “This morning, the government and the Bank of England facilitated a private sale of Silicon Valley Bank UK to HSBC.

“Deposits will be protected, with no taxpayer support I said yesterday that we would look after our tech sector, and we have worked urgently to deliver that promise.”

HSBC is one of the global behemoth banks that is constantly under scrutiny for a long list of crimes. They paid $1.9 billion in fines for laundering drug cartel money. They seem to be constantly at the center or near periphery of Ponzi schemes coming out of China. In fact, the HSBC leadership is said to have essentially merged with the CCP. Perhaps it was the bank's hands-on familiarity with complex financial crimes that led FTX to hire one of its executives to act as their chief intermediary with the traditional financial sector.

Note also that HSBC facilitates the plurality of banking between China and the Bay Area.

The takeover was said to be a fully competitive process, with numerous entities vying for the prize.

Prize?

It's almost as if this isn't a real crisis…

It's not. Well it is, sort of. This is like a lit match in the hand of the Joker in a crowded theater full of people watching Firestarter.

There is the intention of making a scene. We need to understand why.

Yesterday, I started on a "Why Silicon Valley?" story, but we aren't yet to the punchline—or the questions that might help us understand a punchline. I barely said a word about Silicon Valley. But as the VCs like to say about the favored pet disruptions, "It's coming."

Hopefully, by the end of this article series it will be clear why the Silicon Valley Bank run is almost surely an artificially engineered event. That event is likely designed to push the U.S. into a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) to ascend to reserve currency status.

But before we get to the heart of Silicon Valley, we need to discuss contagion, interest rates, and the Federal Reserve…

Contagion?

I'll keep saying it: The Plandemonium is about money, not a virus—not even a vaccine. The global economy is the real crown jewel of crime. That's why this is World War E, which is in turn why the psychological warfare dial is turned to "overload". As such, it should be the default to assume that the War Rooms are staffed with people who have some understanding as to what is taking place, and how it will play out. Keep that in mind.

So, what just happened, and what is continuing to happen?

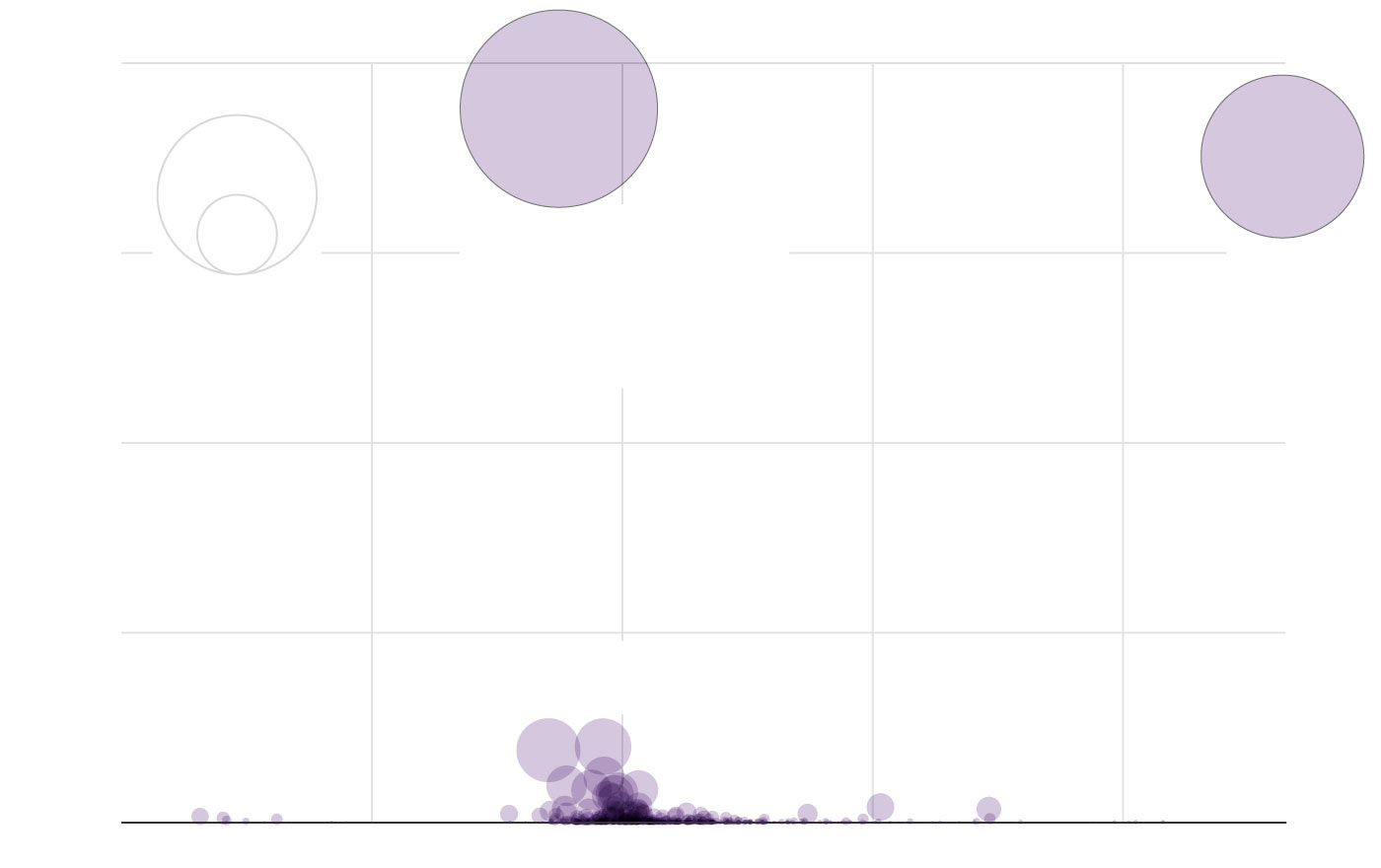

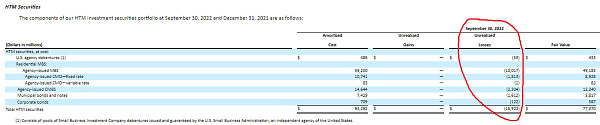

What happened is that SVB had a bunch of bonds on their balance sheet. And by "a bunch", I mean billions and billions and billions of dollars worth of bonds. A hefty portion of these bonds represent long time horizon risk purchased with short term deposits. This took place during an era of rising interest rates—something we'll talk about more in this article. The value of these bonds cratered, and then SVB sold them at a loss, leaving them with an immediate hole in their balance sheet. Remember that last part, because nobody seems to be commenting on it, and it's the key to understanding this situation.

Before we build up an understanding of bonds, interest rates, and the banking system, let's talk about the so-called contagion spreading through the banking sector.

Yes, there are likely some other banks that made part of all of the mistakes (or "mistakes") that SVB made, but the "all of the mistakes" part is likely very rare.

What people are thinking is, "Whatever happened at SVB, it could also be happening at my bank. I better get the uninsured portion of my money out [if not all of it]." So, people are moving to exchange digital account numbers for [admittedly nifty and high tech] pieces of paper to stuff under their mattresses or bury in the yard.

But do people really know what happened, and why it might or might not happen at their bank, specifically?

It doesn't matter. So long as people think it's serious enough, and believe that they understand the cocktail conversation points as they might appear in a too-late edition of The Economist or The Atlantic, they'll talk themselves into believing that they understand it all well enough to take action. And they've been given a weekend for fear, uncertainty, and doubt (FUD) to fester.

Maybe this is all another joke about terrain theory.

Jokes aside, once the "We should worry" news spreads, the many companies banking with SVB rightfully wonder how they're going to pay employees at the end of the week.

On Friday, the FDIC took over the failed Silicon Valley Bank after it buckled under the weight of tens of billions of requests for withdrawals from depositors. All weekend, questions swirled around the status of depositors with more than $250,000 in the bank, who are not protected by FDIC insurance.

While it is well known that these depositors don’t get the benefits of FDIC insurance, because of Silicon Valley Bank’s relationship with many businesses and business services companies, executives were scrambling on Friday and over the weekend to find cash to meet payroll and other basic expenses. There was also worry that other banks with high levels of uninsured deposits would face deposit withdrawal pressure if Silicon Valley Bank depositors were not made whole.

All those smart people and nobody ever suggests negotiating a sliver of the bank to be kept in dollar cash reserves to settle two weeks of payroll. FFS.

Meanwhile, Janet is Yellin', "Too Big to Fail," in so many words.

At least, certain media can portray things that way. Yellen's message is actually that the banking system is on solid footing. Is she hinting at a Fed pivot on interest rates? Or is it perhaps simply the case that most banks don't mismatch their time horizon liabilities by unbelievably obscene amounts?

In the minds of many fearful Americans, the intervention (not a bailout, but a managed out) is therefore correct and justified for the federal government to step in and go beyond its usual deposit guarantee.

Reasonable Question: "Is a managed out better or worse than a bail out?"

That all comes down to how it takes place. Currently, we are seeing consolidation of banking power into corrupt hands. That should worry everyone. From The 2nd Smartest Guy in the World,

There is a new systemic risk. This isn't just a matter of encouraging bad behavior. It's a matter of encouraging behavior that forces the complete rollup of the world's financial sector under one roof. And if you're at the top of the food chain, you just need to leverage one compromised risk manager in a handful of banks to set the whole theater on fire—one match at a time.

I mostly like Kim Dot Com, and I used to appreciate the majority of his takes, but after the U.S. government has Kim's home invaded from an ocean away, and courts ruled it legal, I've felt as though some of his takes might be…cleverly suspect. Maybe the U.S. has his balls in a vice grip?

In this case, he has the game sort of right and sort of wrong at the same time. Yes, we should expect markets to tumble. But here's the rub: we should already have expected the markets to tumble. I'll explain why.

When the Fed Pivots

You should pivot.

Study that chart very carefully. The bottom graph is interest rates. The top graph is the S&P 500, put on a lognormal scale (which basically transforms such graphs from exponential curves into upward trend lines, plus or minus some noise). Now, you might be wondering what is meant by a "pivot" with respect to the Federal Reserve System (henceforth "the Fed" or "the Central Banksters"). Notice in the bottom chart that each arrow points to the end of a period of rising interest rates followed by a precipitous decline in rates. That inflection point where the first derivative goes from zero to "pathologically negative" is the pivot point.

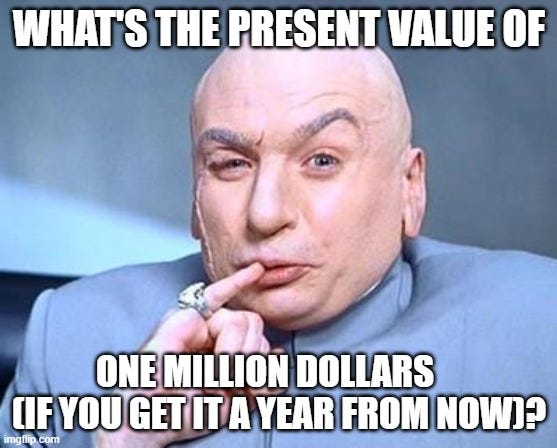

Now, let's build at least a basic understanding as to what the relationship between markets and interest rates should look like. In order to accomplish this, I'd like for you to imagine two universes—one in which the interest rate is 2% and one in which the interest rate is 8%. Suppose I give you the choice as to which universe to live in, given that you will receive one million dollars in each of them—but only after you've been there for exactly one full year. All other things being equal (Russia invaded Ukraine, Fauci is a madman, you don't get to date Tom Brady or Scarlett Johansson), which universe would you choose?

I built a simple spreadsheet to help answer this question. Understand that this sort of analysis gets much deeper and more complex among Wall Street's high quality quants. There isn't just one interest rate, and the rates change over time, so we have to "bootstrap" interest rate curves from an array of "now-to-N-years-from-now" data in order to estimate point-by-point momentary interest rates. But you don't need to know that. You really don't have to go to Quant College to get the basic idea.

What we care about is today's value of one million dollars (one year) in the future. If we think of that cash flow as an asset that we could buy or sell today, at what value would it trade?

Here is the answer:

If you take $980,392.16 and add 2% (multiply it by 1.02), you get a million dollars.

If you take $925,925.93 and add 8% (multiply it by 1.08), you get a million dollars.

The present value of one million dollars in the lower interest rate universe is worth more than the present value of one million dollars in the higher interest rate universe. This means that you are wealthier in the lower interest rate universe than you are in the higher interest rate world based on the same set of future income.

Naive question: "So, why doesn't the Fed just make interest rates as low as possible so that we're all fabulously wealthy?"

The Fed gets to set interest rates, but they'd create an uncompetitive and fragile economy if they did not stay within some parameters. In fact, I'm going to argue that the Fed went outside of the best parameters in order to engineer momentary fragility. And they're likely working with some of Silicon Valley to accomplish the feat. Ahem.

Has anyone at all bothered to ask Steve Kirsch—a man of dubious financial literacy (at least at the serious game level)---why he was building a Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) prior to the plandemonium?

Never mind…

Now, understand that changes in interest rates can have massive effects on bond valuations. I'll simplify bond finance by considering a bond package that pays the holder one million dollars a year for ten years.

Given a 2% interest rate, the bond is worth $8,982,585. And a penny. That amount is the sum of the present values of the ten million dollar bond payments. For instance, the Year 5 payment is $905,730.81. If you multiply that number by 1.02 to the 5th power, you get a million dollars. The process is the same for each of the other nine cash flows.

Now, let's see what happens to the value of that bond when interest rates rise to 8%.

That bond just lost a quarter of its value. This is not precisely what happened with SVB's bonds, but it should give you the basic idea. Now, scale the loss of value we see from rising interest rates to the bond portfolio of a sizable bank with $200 billion in assets, tens of billions of which are kept in bonds.

Houston, we have a problem.

Don't think that nobody noticed. This tweet is from January 18th.

OF COURSE SOMEBODY NOTICED!

This is the sort of thing that the quants in finance are trained to understand. And there is no universe in which some of those very smart people in Silicon Valley who could be paid for their understanding of bond math were not part of the management of that giant, heaping, gargantuan pile of money. M. O. N. E. Y.

This is sort of like zoonotic transfer of a virus in a city where none of the animals test positive for the virus. It didn't happen. By that I don't mean that I have information that somebody internally sabotaged the balance sheet at SVB, but if you tell me that's impossible I'll laugh, then slap you, then laugh again and ask you if you need another one. And then you'll thank me.

Now, I usually don't post the same chart twice, but it's warranted.

Notice that the market crashes or corrects after each pivot. It's like…magic.

Magic.

Reasonable question: "If this market correction is predictable, why does it still happen?

Correct question.

Even in financial markets, most participants don't have a good grasp of how interest rates affect valuations in the market. A lot of financial literacy is half-formed, and stunted by what I suspect is a deliberately poor up-front education within a public schooling paradigm that is, by design, blatantly at odds with…markets.

Rising interest rates depresses the present value of all future cash flows. Long ago, the Central Banksters realized that they could wind up the economy to overheated levels with low-interest easy money, bolstering the values of their own investments. And they can make it look good. As the stock markets tick up above the historically expected exponential trajectory, nobody complains.

All this happens because somebody wants for it to happen. The Banksters don't just know all this. They know it very well. It is their job to pay attention to these sorts of historical relationships. And the implications could scarcely be larger. They begin raising interest rates, then sell off their own equities before pulling the rug on the markets. Notice how many market analysts miss the point, predicting the pivot before the pivot. It's always the young analysts who haven't lived through enough corruption to get over the "cynicism hump" to basic rationality. They honestly believe that the old Fat Cats are bungling the process, then go out and take a poorly tested gene therapy product to protect them from a virus that mostly only hurts old Fat Cats.

Oh, you sweet Summer child.

One defense of the Fed might be, "But they're raising interest rates to cool off the overinvestment in the cycle…"

Oh, you sweet Summer child. The cycle is intentional, and controlled.

Note that those two market bottoms are approximately where the market would be now if we drew a trendline through all the market bottoms of our lognormalized "Fed Pivots" chart. That's no accident. That's also where we're likely headed. Buckle up.

In August of last year, Goldman said that a Fed pivot would not be justified in early 2023, which is the surest sign that we would head into one quickly. Remember, Goldman is one of three large banks given $1.5 trillion to play with during the Plandemonium.

We're not yet to the Silicon Valley connections, but as usual, I need sleep at this hour. More to come…

The asset liability mismatch run by SVB is the same as that being run by all central banks who used Quantitative Easing since the Global Financial Crisis. In essence they all bought long dated fixed rate government and corporate bonds financed by floating rate loans (aka central bank reserves) from commercial banks. The long dated bonds (in SVB’s case described as HTM hold to maturity aka hard to market) are now valued at less than cost and are expensive to hold as the floating interest rate is above the fixed yield of the bond portfolio. This losing position is backstopped by the governments aka the taxpayer otherwise central banks would be filing for bankruptcy.

Central banks in this position include the Fed, Bank of England, ECB, Bank of Japan, SNB etc.

I have many thoughts, I always do when I read you, they all boil down to this though- thank you! Not just for this article for all your writing and for wanting to share and get us all engaged and better informed. I appreciate you for your tenacity and care 😊🙏