Other Education Wars articles can be found here. Join the MetaPrep educational community.

Late in middle school, I was part of an event that should have woken up the world to how far most students are from their educational potential. The result could have been advertised to great effect. Instead, there was total silence.

Some Background

Growing up in my family wasn't easy. For the moment, I'll leave out the details, but my family was involved in a cultish religious organization. What might have been a benign set of religious teachings involved a harsh twisting of principles that led to a great deal of violence, and other destructive behavior. Many of the children in the organization wound up drug addicts, criminals, or victims of twisted or brutal crimes (most of the rest of which do not have handy links, and may never come to light). Some of the children who grew up in the organization, including my brothers, wound up murdered, committed suicide, or dead from drug overdoses. Having rejected all that at an early age, (though it was certainly a progression), I became the black sheep of the family. That unofficial designation came with several beatings a week until I was old enough to force an end to them.

So, from early on, my family experience was a roof over my head, clothing, meals, and a shower of emotional and violent punishment for not going along with "the program". As such, I became a highly independent child, and spent that independence trying to figure out what was going on both with my family and with the larger world. I also had a great deal of time for meditations on my own interests.

I took control of my own education early. While that sounds like a responsibility, it was the most joyful aspect of life. It included a lot of (albeit slow) reading, and discovering a wide array of meditation techniques. Most of this took place wandering around my neighborhood, the woods behind our neighborhood, or under my bed—a bed with three draws that I could pull out, crawl behind, pull back, and would provide me with complete cover from the family. Primarily, I hid from an extremely violent brother, but also my mother whose emotional state largely drove his violence. It was during this time from ages five to nine, that I self-discovered most of the techniques that I used to become a lightning calculator. To me, handling numbers was like playing golf or solitaire—except that numbers were clearly more useful than most things I could be working on.

But like I said, I was the black sheep. It was clear that my brothers (three and six years older than myself) were being promoted to the community, just as most children are by parents. It was just as clear that any invitation to join the process came with a different price—a level of violence that likely would have killed me, and most of the time I expected that I would die before completing school.

Shortly after I turned ten, I got out of bed to get water. Upon entering the kitchen, I saw my sixteen-year-old brother, Andrew, passed out on the kitchen table next to a bottle of alcohol and lines of cocaine. While tiptoeing slowly into the kitchen, I realized that we weren't alone. There was a stranger in the kitchen who saw me and immediately drew a gun and pointed it at my head. We could not have been eight feet apart.

I turned and ran. Having run from violence more than a few times, I had a practiced path that zigzagged out of the kitchen, into the den, into the living room, and out the front door, which I threw closed with a slam. I jumped down the five brick steps and hit the unmortared brick path and rolled. I got up and sprinted to the bush and tree line that separated our house from the neighbors house. I picked the best bush to dive under.

It was pitch black, and all I was wearing was a pair of white underwear. And it was damp under the bush. Petrified, trying to catch and control my breath at the same time, I felt like a hundred bugs, worms, and slugs were crawling on me. Fortunately for me, the night time temperatures around the end of Summer weren't that bad, but I was still cold. I had probably run, jumped, and run again for only fifteen seconds, but now I felt paralyzed. I had no idea what was going on, and I began to imagine that this man with a gun was there to kill us all.

Was he laughing as I ran out of the house? When I stopped to think about what I'd just seen, I was immediately unable to process what happened between the time the gun was drawn and when I found my hiding spot. I think he laughed when I ran, but the longer I thought about it, the less sure I was. And now my mind was on the rest of my family. All I could think was that this man was going to murder everyone still in the house.

I wondered what to do. I had to do something, but I couldn't imagine what I could do to get between this man and the rest of the family who were all asleep. Lying there under a bush in the silence, I listened for gunshots. My child's mind wasn't even sure what I was listening for, and suddenly I thought I heard gunshots (I had not, but it would take me a while to know that for sure). For me, the total silence had a way of making a little sound become what I was worried about. At some point I heard a car start on the other side of our house at the end of the driveway. A car pulled out and drove into the circle to which it connected. It stopped there for a moment, and then the driver accelerated quickly down the street.

After a little more time, I got up and pulled leaves off me and brushed myself down quickly. Shivering, I made my way back through the front door, which I did my best to open without making much noise. I slowly crept into the kitchen. My brother wasn't there. The bottle and the cocaine were gone, too. I walked to the hallway and quietly opened his bedroom door. He was in bed. I slowly walked around the litter on his floor toward his bed to see if he was alive until I heard him snoring. Then I went and checked to make sure my parents and my other brother were alive. They were all asleep. So, I took a warm bath.

The next day I told my parents about what happened, and they declared that it was impossible. They had a belittling way of laughing these sorts of things off. They were still in complete denial that my brothers were using and selling drugs despite the fact that they chauffeured my then thirteen-year-old brother Chad (the family bard who was self-taught on a few dozen instruments) around while he smoked cigarettes out the window of the family car. If they knew that Chad, barely a teenager, was already crawling out the window to sell drugs to high school kids or play guitar at bars in Birmingham, they could not admit it. That's the way things were—narcissistic denial. Since the decision had been made that Andrew and Chad were to become leaders (an enticing suggestion through a very real, if bizarre sounding program run by the head of all U.S. military intelligence), all of their flaws and crimes were seen as something like acceptable externalities. Justifiable casualties. And since I made it a point of bringing them to light so that they would hopefully be dealt with, and perhaps there would be some hope of reconstituting family relationships, I was consistently punished. Even depersoned. Sometimes days or weeks would go by without anyone in the house speaking a word to me unless we were at the dinner table, or I was going to take another beating.

After each of their deaths, and the death of one of my adopted brothers who was murdered in prison, dozens of people would reach out to me with stories about them including theft, assaults, organized crime (including "The Grateful Dead Family" which had both Pharma and intelligence ties, and organized the larger part of the drug trade around Phish and Grateful Dead concerts), and some stories strange enough that I usually leave them off the list because they aren't easily believed by many "normies" and "skilled TV watchers" for whom anything unusual is, "out of sight, out of mind, and not generally related to the reality of ordinary experience." It's the same sort of mindset required for mass formation, and gives way to the banality of evil.

In high school, I became something like a counselor for Chad's many victims. Instead of knocking on my window looking for drugs, they would knock on my window and we would go for walks in the neighborhood. I got into the habit of sleeping at 3 or 4 in the morning. It would surprise most people how many points of trauma one person can establish. People who knew me, who knew how hard I worked, and how much I read, often asked why I didn't work for perfect grades during high school. Others (the kids for whom top grades were something like a religion) actually believed I was lazy. I earned exactly six B's, all of which were 89's while I skipped any homework I couldn't complete during other classes during the day, or slept at my desk. This distinction between seeking status from academic "work" and the truly twisted and knotted problems of the world strikes me as something like the reason why we can't have nice things. It's at the core of murderous American narcissism, the Malthusian mind virus, and Moloch. It's the illusion at the core of the quest for immortality.

Children growing up knowing how to get grades, but not knowing how to pick up another human being slumping nearby is a significant piece of the puzzle as to why we seem to be degrading as a civilization.

How This Became a Story About Education

I never belonged in school. If schools are prisons for some people, it was far worse for me. There was never a moment when I was in a room that was the right place for me, and I eventually realized that it was not the place for anyone who took control over their own education.

When you learn by following your interests, the signals you emit confuse the teachers who are only trained to conduct a highly linear path. In the first grade, I was moved from the lowest reading group to the middle one, and months later to the highest one. At no point did anyone realize that I knew all the words, but simply had trouble reading aloud, despite my explaining it numerous times over. For years I would get in trouble for bringing my own books to school to read (some of which were apparently "inappropriate") while ignoring the next exercise of coloring inside the lines.

Of course, many thousands or millions of people have similar stories, but it now feels like an important moment to focus on the clear bifurcation between how those who were guided by schooling, and those of us who were not.

Some of these differences will be attributed to IQ or Charles Spearman's conception of general intelligence, g. This is part of the reason why I've preceded this particular article with those about the Benjamin Bloom problem and interventions that close the gap for impoverished children. So, while I think every human is special (just being alive is special), I think that most of what makes educated people feel special is illusory. Sure, we can take credit for work, but the distinction is often having the basic opportunity while not getting railroaded.

Understand that this perspective does not deny that (epi)genetic influences are at play. They always are. But this is little different from the fact that athletes tend to be a little taller than average. Whether or not you can play a sport professionally, you can become quite athletic—often even beyond the professionals who take it easy after retirement. Practical development of skills dramatically trumps most natural advantages unless the games are as specifically formulated as putting a ball through a hoop ten feet high. Even where height does bring advantage, nobody plays professional tennis without putting in a lot of work, and Michael Chang does exist.

Academics are a flatter playing field. If you're free of health issues, and your time isn't elsewhere committed, you can work, learn, and succeed.

When I entered the sixth grade, I was allowed to join the PreAlgebra class with the strongest seventh grade math students, and to join their math team. Fortunately for me, the math team coach, Cindy Breckenridge, recognized that I was fine taking my own road with math. She was a pioneer among programs such as Mathcounts that encouraged teachers to think of themselves as coaches, and held annual local, state, and national competitions. Her math teams would win most contests around Alabama, and often placed highly at national events.

Up to that point, I was always the student in class teaching the other students math. It didn't matter if they were the best student in the class, or the worst, or that they were a year-and-a-half older. I would sit next to students and talk with them until they understood fractions or decimals or whatever else challenges kids that age (mostly fractions and decimals). Perhaps because specialization had not yet divided the students completely, and perhaps because growing up in the local drug distributorship, where hippies, punks, strippers, musicians, and guys who carried weapons were daily life, I wasn't a nerd among the students. I played sports and road skateboards with some of the other kids, and never had a sense of nervousness or fear about any of them.

Now I was in class with only the students who wanted to take the harder academic road. And I was still the one they came to for help with hard problems.

A few weeks into the school year, Mrs. Breckenridge invited me to start staying after school some days to practice with the seventh and eighth graders eligible for the Mathcounts competition (sixth graders were not allowed to compete at the time, but are now). It was the first time I'd ever seen challenging problems. There were new notations, and a need for geometry facts that I hadn't been introduced to. Mrs. Breckenridge would let me take home stacks of the practice problems.

At this point, I'll mention that I had very little sense that people learned math from books. The idea was entirely foreign to me. Sure, we started having hard bound math books in the sixth grade, but I thought that was just where problems lived. I never had to actually read any of the section lessons. And thank God for that given how slowly I read. I just grew up listening to my older brothers or adults talk about concepts, thinking them through, practicing computations in my head. I got plenty of additional practice teaching other kids about fractions and decimals. Now it was a strange shock to find out that there was so much more math that it had to be kept in books. Even worse, I didn't have these books called Algebra and Geometry.

So, I would take home stacks of problems, and invent my own methods for solving them. During math team practice, I would soak up the basics of algebraic notation, and a few geometry concepts and formulas, then work out details and explore patterns for myself. I filled dozens of notebooks with patterns, relationships, and formulas that I would make up.

At least partially because I was dyslexic, I did not win any of the math competitions that year, but I was still the kid that the others came to ask for help, and sharing all the different ways I came up with to look at problems became the only part of school I enjoyed (other than talking to cute girls…I was paying attention to girls by that time).

The Summer after sixth grade was the greatest adventure of my childhood. Almost every day, I would pack a lunch, hop on my bike, and ride it a mile-and-a-half to the civic center where our local library was situated next to a gym with basketball courts, with tennis courts a short walk away. All day long I would play basketball or tennis, and take breaks at the library where I started reading math books. It also turned out that not being home all day was a great way not to have the crap beaten out of me.

The first book I read was the Saxon Algebra book. I would read the definitions at the start of each section, then work the problems at the end in my head. Because I'd seen so much basic algebra during math team, I was mostly just soaking up a small amount of vocabulary and notation, so I could go through a chapter in ten minutes. Then the next day, I read the Saxon Geometry book. The Saxon Algebra II book took me two days.

For what it's worth, the Saxon curriculum is extremely shallow for any student who wants to understand the math, and years later when I started writing math textbooks, I thought of the Saxon books as what not to do.

Still, those days in the library gave me a foundation from which to continue exploring math. Where concepts were undercovered by those books, I figured out enough to make up my own methods and formulas, often by taking problems from competitions written by math-proficient adults, and seeing what I could generalize. I came up with hundreds of relationships that most people would never think to explore unless asked in a class, like how the differences between consecutive perfect cubes were always one more than six times a triangular number and how the hockey-stick identity works (though I didn't yet know what it was called).

When school started back for the seventh grade, I placed second at my first Algebra math tournament. All six of the problems I missed were reading mistakes as I rushed through the work, so I spent time learning to frame problems better as I was reading them. For the rest of the year I won all the local contests, usually by wide margins, usually without missing a problem. I could often finish the hour-long tests in five to ten minutes. But my real goal was to do well at Mathcounts. I knew that I could solve every problem, and by the time those competitions started, I'd dealt with the problem of reading and answering problems too quickly. I made the highest score at the state competition, so I made the four-person team to travel to Washington D.C. to compete at the national competition.

The night before we left, I meditated on all the practice I'd done. I couldn't get to sleep for hours, and instead spent the time convincing myself that I could solve any problem they threw at me.

The competition took place at a hotel with a giant ballroom. The contest, which was aired on ESPN for some time, was made up a bit like a game show for nerdy kids. It felt weird hearing somebody sound official over a microphone give directions to a room filled with 228 kids, their state coaches (Mrs. Breckenridge was ours), but I got over that pretty quickly. I aced both the individual competition, which had not been done in any previous years. Then came the Team Round, and we had a bad day missing three of the ten problems (we average missing one during practice), and the team finished seventh place. The top individual scorers were then invited on stage for a buzzer-style "Countdown Round" to determine the national champion. I kept listening to the problems and solving them immediately as the other kids competed, with one getting knocked out each time. Finally, I competed for the national championship. I couldn't read the problems on the screen with the moderator talking. Problems that would take me one to five seconds were suddenly preceded by five to ten seconds of somebody's voice, and dozens of lights aimed at the stage rendered me word blind. So, I finished second, and won some scholarships for my troubles.

In the aftermath, something struck me. I could hear people talking about me—the long-haired kid from Alabama who achieved a perfect score as a seventh grader. What surprised me was their surprise. It was if they thought that kids from Alabama weren't supposed to be able to learn how to solve math problems. That was absurd, of course, but there really were people who didn't realize that it was absurd. A couple of adults who congratulated me even stuttered it out, around it, or stopped themselves from saying it—kids from Alabama weren't supposed to do math well. This included reporters from the media who came and asked me questions about myself, and wanted quotes.

I didn't realize how much it would bother me for people to express surprise, but it did. That fueled me to conduct my own experiment.

The Goal: Alabama Wins National Mathcounts

After the seventh grade, I once again had a Summer of almost complete freedom, but with my own imposed structure to it. The high school math team coach, Kay Tipton, invited me to join students who recently finished their sophomore year to compete at a national competition run by the Mu Alpha Theta Honorary Society. I had just finished Algebra I, but would need to learn more about geometry, trigonometry, complex numbers, and a few topics in order to really compete. I would learn about those from the other students while teaching them all the techniques I had invented for solving number theory, combinatorics, and probability problems. Mrs. Tipton held practices during the summer that I attended. I finished third place at the event, and our high school won its second national championship. Having outscored the kids three years older, I had solidified a local reputation. This would make it easier to lead classroom and study sessions with other kids.

I also grew six inches that Summer, and continued to play tennis and basketball, and skateboard in my spare time. I got a lot stronger, and that led to an important moment. My brother Chad was used to throwing his rage at me with impunity, but suddenly I was only two inches shorter than he was, but stronger. He attacked me one day for some reason that I've long forgotten, and I did what I'd become accustomed to doing, which is choose the hallway of our home as the battleground. I'd learned that I could put a foot against the wall for leverage, and do a pretty good job of keeping him from getting full swings at me. He would tire me out and then land punches, but not as many would hurt as badly as if he could push me into whatever position he wanted and then swing away until he was arm weary. But this time, when I put my foot on the wall, I could push him a couple of feet to the other wall, and then I pushed him sideways to the ground. It surprised us both and he pulled his legs up to protect himself. I could have dished back a beating that was certainly coming to him, but I just stood over him, surprised. A few times I let him know what would happen if he came at me again, but those fights were over for good.

A few days I took him down in the hallway, I woke up one night with him on my bed with a knife to my throat, telling me that he was going to kill me. My arms were pinned under his knees, and I didn't dare move. He had come back from playing guitar at a club, drunk and addled on whatever drugs were available. I couldn't understand most of what he was saying. His eyes were red all around, and bloodshot. I didn't say anything at first. I always worried that he would kill me, or possibly my parents. After a few seconds, I said deliberately, "I don't want to hurt you," the way you might think, "I don't want for you to hurt," and then he pulled the knife away. He swayed a bit, and then he passed out on top of me. I spent a couple of minutes climbing out from under him, wondering what to do. I eventually just picked him up and carried him to his bed.

A lot changed around that time, and I gradually realized that I'd created so much attention that year becoming the math all star that I was no longer invisible. That might have saved my life. Instead of having no relationship with anyone in my family, my parents began making it publicly clear that I existed as their son. We still never had much in the way of conversation, and most everything they would say to people about our home life was entirely fabricated since we barely talked and I would hang back from most family gatherings. But it was clear that if I got out of the house healthy, and with scholarships, our clusterfuck of a house wouldn't look as bad as if they just sort of let Chad kill me, negligently, with plausible deniability over how they were (or weren't) steering the ship during his descent into chaos.

Essentially free of Chad, I became free to plan out almost all aspects of my life for a while. And the plan that I wanted to execute was to build an Alabama Mathcounts team that could win the national championship. I wanted for people to understand that what we did in school was a complete waste of time, and that if we did things right, everyone could learn much more and do much more.

Also, fuck those people who didn't think it was possible.

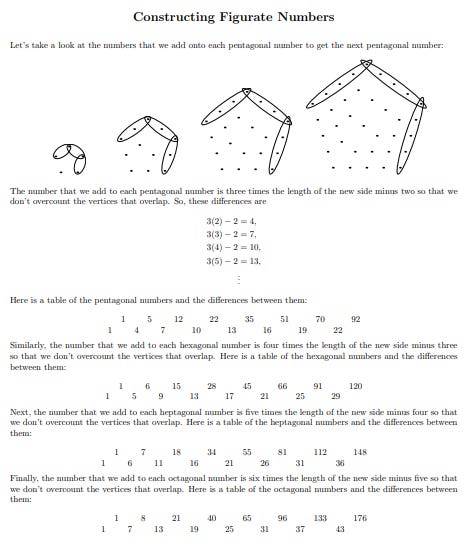

I started holding my own classes for other students. Mrs. Breckenridge would open up the middle school math team room for me to do it. I would charge students two dollars for a two hour class. Within a few weeks, there were forty students coming every week from the middle school, the high school, and from other schools in the area. I wouldn't just teach them methods or formulas that they hadn't seen, but give them assignments that would allow for them to play with numbers and discover on their own. I didn't want for them to memorize formulas with no context, but to understand, for instance, how figurate numbers are generated, and then to apply what they already knew about summing arithmetic series to derive their own formulas.

During that time, I learned a lot about how people absorb information. In particular, for anything complicated relative to their current state of understanding, it was best to have them write it themselves. Also, using multiple colors to distinguish different parts of the process allowed for people to switch focus in a useful way.

But most of all, people learn best when they get interested in the topic. And people get interested in topics that relate to them. That can even mean simply having the attention of somebody with knowledge. Many students I worked with would become more active and alive any time I stopped to work on a problem or concept with them.

At home, I would answer phone calls from students who were stuck on problems. And then I'd get to chat with the girls, which eventually turned into a few dates. So maybe not all of that time spent was entirely selfless.

None of the other students were quite aware of what I was doing. A few times I told them that Alabama could win the national championship, but none of the rest of them had yet competed in even a local Mathcounts event. And looking back, I don't think that any of them really knew that it was possible right up until the national event.

When March rolled around, my school and the school about five miles away dominated the state competition. The four of us who made the state team all lived in a circle with a radius of about three or four miles. We often studied together, and I could ride my bike to their houses (and sometimes did to the chagrin of their parents who weren't accustomed to a thirteen-year-old setting his own schedule and going where he pleased).

I was a little worried about the team because one kid who lived about three blocks from me, and with whom I studied with often—and whom I expected to be around third in the state—had a bad day and did not make the team. I thought he had an outside chance of being in the final 12 at nationals. But the team was still very strong. Most of the time that we practiced, we solved all of the problems on the hardest team tests. Any time we missed one, I created a study session around the topic. Ten hours of work seemed like a small price to pay to close every door.

In May, we flew to Washington. Unlike the previous year, we made a perfect score on the Team Round. More importantly, the Alabama team was the only team to solve all ten problems on that most important test. I missed a problem during one of the individual rounds, and failed to repeat as a perfect scorer. Once again I came in second place again after once again stumbling in the Countdown Round. After the Team Round, and long before the awards ceremony, a student from Massachusetts came to our table and introduced himself. He had also missed one problem, and was the eventual individual winner, but he told us about his team's estimations of their individual scores. If he was right about their scores, even though his team missed one problem on the team round, they would outscore us overall, by a fraction of a point. The other members of the Alabama team did not seem to be paying attention to the discussion of the scores, so I didn't mention it to them. I expected that we would be second, or possibly third place overall. I was uncertain as to whether we had the only perfect Team Round.

When the top ten teams were announced, I listened for the names of the big states like New York and California. When New York had been called, and California was third, I was relieved. My teammates were just sitting, facing the stage, listening, as if they had no expectation that we were even involved in this whole event. One or two of them mentioned being worried that we might not be in the top 10. Then Massachusetts was announced as the second place team. I finally looked around at my teammates, seeing that they had no idea, so I told them, "We did it." They were dumbfounded and everyone's eyes got big. Then Alabama was announced as the winning team, and we all jumped up and down, and then went to the stage to receive big plexiglass triangles that are the hallmark awards at Mathcounts. Later, our coach, Mrs. Breckenridge, told us that we won by the smallest possible margin—a quarter of a point.

Have We Learned Anything?

BLUF. Bottom Line Up Front: The following should have been realized by every observer at the national competition, though some of that would have only come out with an interview.

A far higher level of math can be coached to young people.

A far larger proportion of students can learn math more advanced than is usually imagined by our dull school leaders.

Children can self-direct their own education to a large degree.

Students learn through active engagement.

Students learn by teaching.

Alabama (and a lot of other states that aren't necessarily built around metropolises and major university cities) have tremendous amounts of untapped educational potential. And for God's sake, nobody alive remembers the Civil War that still defines one of the most absurd and artificial social boundaries in Western Civilization.

Having been through the aftermath of the event a year earlier, I expected for the Alabama team to be surrounded by reporters the way that the Ohio team was the previous year. Years later during college, I was in the same scholarship program as one of the members of that team who confided in me that there were so many people (mostly reporters) all over them that he puked.

That's not what happened with our team. In fact, not one of the reporters even approached us. I saw several stare at us, then retreat elsewhere. This didn't bother my teammates who had no expectations. They were barely aware that there were several dozen members of the press running around the perimeter of a circle centered on us, interviewing the boy from Massachusetts who won the Countdown Round, sure, but also just about everyone they could find who wasn't from…Alabama. But I could see the stark difference from the previous year, and I remember the way people commented about Alabama then.

Mr. Breckenridge noticed, and she grew irritated. She had been with the Mathcounts program since it started a decade earlier as a pilot program with no national event. She gave her soul to her teams and the event. And she was damn proud to coach many of the state teams to Washington, and a winning team this one time. She all but dragged one lady over to us who briefly asked us a couple of questions before hurrying away like lunch hadn't settled with her.

A few days after we returned to Alabama, I saw Mrs. Breckenridge after school, pacing around, infuriated about something again. "They're not inviting us to the White House," she told me. This was important to her. While I'd known about the tradition after spending a week at Space Camp with the other winners from the previous year, I was personally more excited about another free trip to Space Camp. That wasn't the sort of experience my family could generally afford. But it began to sink in: we were snubbed by the press, but a trip to the White House was a tradition that would have publicly (and deservedly) crowned her career as the highly dedicated and impactful teacher.

Our coach was given the excuse that the president was busy due to Operation Desert Storm. But the invasion of Iraq was basically over by the end of February. Obviously, nobody is ever owed a trip to the White House, and middle school math champs aren't Benazir Bhutto flying in from Pakistan for an honorary state dinner as the first female leader of a Muslim nation. But the White House did not exactly clear its calendar that Spring. The introduction of the world wide web and the dissolution of the Soviet Union were still months away.

Maybe Michael Jordan preferred playing golf with money launderers, but it would have meant something to Mrs. Breckenridge in particular to be received by the president.

Maybe President Bush knew what was to come in Moscow, and was busy practicing the Chicken Kiev speech?

Or crafting a New World Order?

Oh, c'mon, I'm just teasing. I…hope.

But this was a missed chance for the White House to make an annual statement about education, and at a time when the STEM push was just becoming more pronounced. And while celebrating education in Alabama isn't the usual script, it could have been a far better story—that a pack of kids in a couple of small communities south of Birmingham could study up and win.

More importantly, our story was an opportunity to spread the word on how to help more students learn serious problem solving skills. Had California or Texas or Massachusetts won, the success of the students could be easily dismissed as "the best collection of individual outliers" from large populations of educated people. Our team showed that putting in the work leveled the playing field—and tilted it in our direction.

Only one state with a smaller population than Alabama's, that being Kansas, ever won the National Mathcounts competition, but certainly none as small as the 40,000 or so population of the two towns in which the four members of the Alabama team resided. Me and the other members of the Alabama team did joke a bit about seceding from the state, then claiming the title. For our tiny new state.

The large and wealthy states of California (4), Texas (7), and Massachusetts (5), have won sixteen out of the last twenty-five national titles at Mathcounts. Partially in part due to a company I helped build that now sponsors the event, there is no longer any lack of preparation for the students who want to study for it, making it close to impossible for smaller states to win. It isn't easy to find slack in any system once it becomes competitive enough. In a way, that's great. But it also means that the opportunity to recognize some of the BLUF lessons has passed.

Where We Are Now

Around 15 years ago, Mrs. Breckenridge was badgered by an administrator for a year until she threw up her hands and quit. That administrator then moved on to another job after just a year at the school. A few years into retirement, struggling with a difficult family life, and without the joy and social support of her vocation, Mrs. Breckenridge shot herself in the head.

Since 1991, a hundred additional stories have confirmed the growing suspicion I had as a child that we are governed by people who do not want for us to understand how well we can be educated, much less that we can do it ourselves. I hope to have time to write about more of them in the future. We do not even have highly motivated leaders in our business community particularly interested in the conversation.

But we have seen "change". A couple of years ago, not long after the pandemic started, one of the members of the 1991 Alabama National Championship team posted this on their Facebook.

I'll talk about common core math another time, but I want to bring your attention to the observation by the great mathematical genius, Benoit Mandelbrot. This comment would have been made in 1999—and he was referring to Bill Gates.

Meanwhile, no serious effort has been made to build a more flexible and exciting classroom, including problem solving, and student leadership.

This is a lot of history I was only peripherally aware of. I was trying to think about what I did over my 6th and 7th grade summers and it was probably lots running around in the woods and playing SEGA genesis. Now I want to know who was on your winning team and what all happened to Mrs. Breckenridge. I had her for pre-Algebra and in hindsight I was really lucky to have her and Mrs. Tipton as math teachers, no one else ever came close (many would actually retard my developments in math).

That was riveting Matthew. Thanks for sharing all that I’m so glad you got that power of mind and soul. It is a treasure!