Unless you were deeply involved at the very highest levels of finance at the time, most everything you've been told about the problems that led to the 2007 subprime mortgage bond crisis that plunged the world into economic chaos, even if you've read alternate hypotheses written by smart academic types, is wrong. I traded one of the largest hedge fund bond accounts on Wall Street during the late 1990s, and I'm going to explain what really happened. At the core, there is a relatively simple story, obscured by invisible information and blind trust. All of this needs to be more widely understood at this moment in time because the world is changing very rapidly, and this story relates to all world geopolitics in profoundly important ways.

In early 1998, a trader at the famous super-quant hedge fund D.E. Shaw & Company (DEShaw) contacted me, urging me to fly to Manhattan for an interview. We knew each other through the U.S. training program for the International Mathematical Olympiad---a program that brought together around two dozen of the nation's top high school math students each year to study, practice, and form a team to compete at the International Mathematical Olympiad. He was six years my senior, but we were from the same state where a small number of us---five in total---had each attended the program over a period of five or six years. We all knew each other. One of DEShaw's hiring strategies was to sift through students from the Mathematical Olympiad Program (MOPpers) and make offers to the ones with good financial or communication skills in addition to their mathematical problem solving skills. At that time, I felt relatively bored with college, spending most of my educational time working statistics work for a local insurance company or building up the new debate team at Washington University in St. Louis, where I was one of the founders and served as team president. Fulfilling degree requirements I felt less passionate about seemed like a more and more soul-siphoning drag. So, I was excited to fly out to New York and find out what all the hedge fund excitement was about.

After five one hour interviews involving mathematical puzzles and what I later surmised were psychological tests, the senior vice president of the bond trading group, Richard Rusczyk, who had invited me in for interviews, walked me from the DEShaw office just off of Times Square several blocks to the train station. The gesture surprised me a bit, but it felt like I was engaged in one more interview. He asked me what I knew about the mortgage bond market. Though my economics geek level led me to follow markets generally, I was not yet even aware that mortgages were rolled up into bonds and sold to banks and investors. The topic was entirely new to me. I cannot recall what all he told me about the market then, but it was clear that he was highly engaged in thinking about it. Perhaps he wanted to see if I was somebody who might trade a mortgage bond account, or better suited for a different trading role.

A few days after I returned to St. Louis, Richard called me and made me an offer to join the firm as a bond trader. Part of me felt surprised that they did not wait until I was done with school, but the larger part was excited to jump into what felt like The Major Leagues of Problem Solving. I accepted the offer and never again attended a college class. At the age of 20, I was headed to Wall Street where I would quickly get in over my head, making my first trades in a highly leveraged, multi-billion dollar bond portfolio before I could legally drink, heading into the Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) collapse that tested world financial stability prior to the mortgage bond crisis.

(It sounds implausibly scary to put a 21-year-old in charge of a bond account with in excess of 100-to-1 leverage into $12B in bonds and $20B more of swap agreements, and yet the kids swimming in large cryptocurrency pools aren't much older. But yes, I do now recognize the divergence between gaming ability and earned wisdom to be an existential problem on Wall Street.)

During the first few days on the job---the calm before the LTCM storm---I was engaged in several conversations about various markets before it was determined that I would become the firm's new Asian bond and derivatives trader after a training period. But the conversations about the mortgage bond market struck me. There were clearly stories beneath stories and very strange puzzles to be worked out. While I cannot recall what I learned exactly when (some or most of the following details I learned after my interviews or during the first few weeks on the job, but perhaps other aspects later when my experience allowed me to more fully absorb them), here is what I found out in 1998…

During the early 1990s, the now-defunct Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN) and other groups filed multiple lawsuits claiming racially discriminatory banking practices related to mortgage applications. A young Barack Obama famously played a very minor role in one of those lawsuits. There are varying accounts regarding Obama's overall participation in ACORN's tactics, but I won't claim deep expertise on the lawsuits and am going to dodge the issue for the sake of getting to my primary point. Former Attorney Generals Janet Reno and Eric Holder were generally involved in that legal activism. Citibank settled a discrimination suit without ever giving up the data that would prove their innocence or guilt. That settlement alone was not that important, so far as I understand, except that it garnered public support for moves made by President Bill Clinton's administration.

In 1993, Andrew Cuomo was named Assistant Secretary for Community Planning and Development at the scandal-ridden Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In 1997, Cuomo would be elevated to head of the department when HUD chief Henry Cisneros resigned "to deal with allegations that he lied to the FBI about payments he made to a former mistress." Throughout the Clinton era, HUD was known as a tool for partisan warfare, but as an organization focused on a mission publicly billed as increasing national home ownership rates. Cuomo was the primary organizer of that process:

Under Clinton’s Housing and Urban Development (HUD) secretary, Andrew Cuomo, Community Reinvestment Act regulators gave banks higher ratings for home loans made in “credit-deprived” areas. Banks were effectively rewarded for throwing out sound underwriting standards and writing loans to those who were at high risk of defaulting. If banks didn’t comply with these rules, regulators reined in their ability to expand lending and deposits.

These new HUD rules lowered down payments from the traditional 20 percent to 3 percent by 1995 and zero down-payments by 2000. What’s more, in the Clinton push to issue home loans to lower income borrowers, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac made a common practice to virtually end credit documentation, low credit scores were disregarded, and income and job history was also thrown aside. The phrase “subprime” became commonplace. What an understatement.

In 1996, several members of the DEShaw Fixed Income group (what we called the bond trading office) went to Goldman Sachs for discussions about the mortgage bond market. One of Goldman's top quants was a guy named Gregg Patruno who had coached Richard at MOP in the late 80s. After the meeting, Gregg pulled Richard aside and told him that the data in the subprime mortgage bond markets was beginning to look very strange and that "This won't end well." The DEShaw traders began to investigate. This included setting up a meeting with then-CEO of Fannie Mae Franklin Raines, whom one person in that meeting described to me as "a true psychopath". But the more important piece of the puzzle came in a phone call with Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan (you can make that kind of phone call when your boss is chummy with the Vice POTUS). When asked during that call if the Fed was really backing all of the subprime mortgage bonds as AAA (as per the "equivalent to treasury bonds" rating mythically endowed on them through the bond bundling process at Fannie/Freddie), Greenspan's one word answer was, "Yes."

Alan Greenspan receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush (Shealah Craighead/The White House)

Now, let's think this through:

Starting in 1995, Cuomo's HUD used both the stick (noncompliance = lower funds from the Fed to fuel lending activity) and the carrot (Fannie/Freddie will buy those loans to ensure virtually instant profit for the banks, as conduits of leveraged Fed funds, and wrap them into AAA bonds to be sold into financial markets so the banks could go out and lend to more and more and more low credit home buyers) to build a positive feedback loop that could only be ended by a politically untenable (both putting the brakes on a hot housing market and also "racist") policy change or an epic market crash.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac rolled up those subprime mortgage loans into bonds like a psychopathic clockwork mint. Initially, this just allows the selling of loans as dollar revenue streams of pooled risk. But the AAA stamp can and should be described as implied insurance, as per the Fed's backing. This meant that the bond buyers got a free lunch out of the deal---it takes a lot of money's worth of insurance to make up the difference between "subprime" and "highest possible credit rating". Market liquidity was all but baked into the process.

Since the Federal Reserve issues as much money as it deems appropriate, there was essentially an infinite supply of dollars with which to issue those loans.

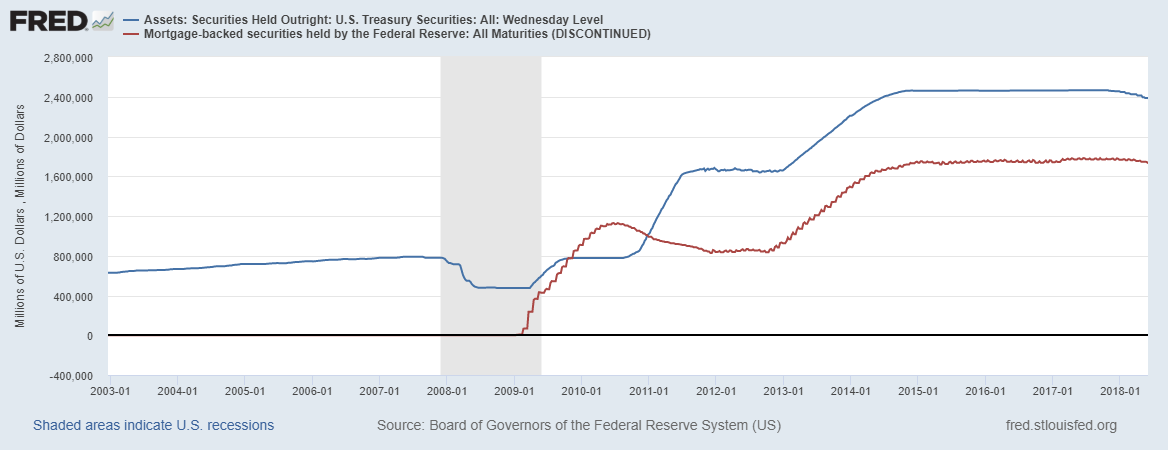

What this means is that the trillions of dollars printed as part of the post-crash policy of quantitative easing were not actually printed from 2008 through 2014.

In reality, those dollars were really printed in the form of implied insurance from 1995 through 2007!

And no matter what has been said by the media's propaganda artists, the entire process was most certainly understood long before the great mortgage bond market fiasco of 2007. I had scores of conversations about it both in person and online for years prior to the crash. Don't get me wrong---it is certainly the case that 99% of people employed on Wall Street were in the dark. Either you were on the inside of the inside of the inside circle, a genius who tracked down all the information necessary to put the pieces together, or you were simply going about your day, hustling as per the job. But the idea that Alan Greenspan failed to understand what he and the Federal Reserve were doing strikes me as absurd to the point of unbelievability. And if the crash was "the quant's fault", we would know the name of the quant who built that faulty model, and when, and wonder why not one of the great geniuses of quantitative finance wondered whether it was wise to trust so much money to one model.

This story is not over. I plan to write about it again. The implications live on, and relate to the Wars of Wars on many levels. But if you have not fully soaked up this story, please reread it and pass it around among your friends and discuss it until you do. Because there is no government of the people when the people cannot understand the machinery of finance that can help the process of centralizing wealth in the hands of a tiny handful of elites.

So basically, they—the inside of the inside of the inside—knew it would collapse and knew they would bail them out…?

Good times.

Will you write about the Great Pandemic Money-Printing (GPMP) of 4+T USD that took place since Mar 2020 and is still ongoing to the tune of 120B/month as of Oct 2021?