“Hundreds of metric tonnes of chloroquine have been dispensed annually since the 1950s, making chloroquine one of the most widely used drugs in humans.” –World Health Organization (WHO), The Cardiotoxicity of Antimalarials

It is one thing to answer the (primary) Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) hypothesis as to whether or not HCQ is effective as a treatment. It is another to answer the question as to whether or not patients should take it. The latter question is our greatest concern. It is an economic question which comes down to weighing the costs versus the benefits. If we determine in our cost-benefit analysis (CBA) that the benefits outweigh the costs, then we recommend HCQ as a medication.

Using similar logic as with our approach to the HCQ hypothesis,

To affirm HCQ use in fighting SARS-CoV-2, the CBA need only show a positive cost-benefit for one form of HCQ, in any combination with other medications, whether given as PrEP, PEP, early, late, or as critical care.

Within that CBA, some risk analysis is inherent. If the benefits clearly outweigh the costs, for any one form of treatment, then we should be happy to take HCQ within that treatment. If no one single form of treatment results in a net positive gain, then we should not. Perhaps also there is a grey zone of judgment, but we are confident that our case pushes well beyond that grey zone for most patients.

For the moment we set aside the possibility that the CBA is different for different people. This is often the case in medicine, but our chief concern within the Chloroquine Wars series is to try to evaluate whether this is the case for most people, broadly speaking. Most of all, we seek to evaluate the hypothesis that HCQ provides prophylactic protection or therapeutic benefit to sufferers of COVID-19, particularly in the early disease stages. The numerous doctors successfully treating most of their volumes of COVID-19 sufferers with HCQ, such as Dr. Didier Raoult, Drs. George Fareed and Brian Tyson, and Dr. Vladimir Zelenko, do not treat every single patient with HCQ. Each one of them works with patients on a case by case basis, or with a system of basic rules to tailor their approaches to each individual case.

The primary costs we take into account in our HCQ CBA are its price (in dollars and cents) and its risks (potential to do more harm than good). Sadly, there may also be social consequences during this extremely politicized age as Michigan lawmaker Karen Whitsett found out when her Democratic Party unanimously censured her for public statements about how HCQ saved her life when she came down with COVID-19. Such consequences are now well known, and most people can trust doctor-patient confidentiality even if they cannot trust their friends not to judge their medical decisions. As such, we move forward under the assumption that social costs are minimal. It is a sorry state of affairs that choosing a particular medical treatment could result in such castigation.

According to drugs.com, the cost of a 200 mg HCQ pill can be as low as 37 cents up to a little over a dollar. More recently, the cost of a 200 mg pill of HCQ is often quoted as around 60 cents, but this may go up or down a little according to the costs of the ingredients. As India, the world’s largest producer of HCQ, ramped up production from 120 million pills in March to 300 million pills in April, short-term scarcity in the prices of ingredients jumped. Still, HCQ is inexpensive, and a full course of treatment for SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 may be as low as $6 or perhaps go a little over $20 for high dose treatments. One of the popular early stage treatment regimens championed by Dr. Zelenko, a medical doctor practicing in CITY, New York, has been quoted as costing around $20, though he lists potential alternatives that could increase that cost. Still, the dollar cost for HCQ treatment is relatively low.

Given that HCQ and the other medications/supplements with which it is usually prescribed as a COVID-19 treatment are inexpensive and widely available, we primarily focus our CBA on the safety profile of HCQ to determine any serious cost to weigh against the benefits. The FDA approved HCQ over 65 years ago and is used by millions of Americans annually. During a typical year, HCQ pills are consumed between two and three billion times around the world. HCQ and CQ are taken by the young, the elderly, the sick, the healthy, by pregnant and breastfeeding women, and by the immunocompromised. A long term study showed that HCQ is relatively safe and even protective of the heart for a substantial number of people. At least one study has concluded that HCQ withdrawal is well tolerated even in older chronic users of the medication.

But there are very real safety issues with the use of HCQ and CQ. When too much HCQ or CQ is present in the blood, side effects can occur. One of these involves prolongation of the heartbeat QT interval (sometimes QTc), which can be easily detected on an electrocardiogram (EKG or ECG). This change in heart rhythm (arrhythmia) can cause serious issues including death in acute cases. Fortunately, this is a well known side effect of dozens of commonly used medications---so common that there is an entire website dedicated to listing all the drugs that have been associated with it---and with diligent monitoring it can usually be detected in early stages, giving physicians and their patients an opportunity to change their treatment plan before QT prolongation progresses into more severe cardiac issues.

How much do these safety issues matter in practice?

Almost not at all. HCQ has been tested for safety for over 30 conditions without results that would raise alarm bells. In small doses, HCQ and CQ are so safe they’ve sometimes been added to table salt in nations where malaria is prevalent.

Statements about the dangers of HCQ could be made to sound scary, but would apply similarly to essentially all other medications and many ordinary life risks we take for granted, daily, like driving a car. Common drugs found in the medicine cabinet are often many times more deadly. According to the NIH, more than 5,000 Americans died from antidepressant overdoses in each of 2017 and 2018. In 2001, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as aspirin and ibuprofin were estimated to be responsible for 16,500 deaths annually. In 2016, the number of deaths attributed to prescription medications of all types was estimated at 128,000. According to information from the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS), a total of 640 deaths have been attributed to HCQ in the U.S. over the past 50 years (many of which are accidental overdoses by children finding their way into the medicine cabinet). This represents around 1 in 3000 deaths in the database. Since HCQ is prescribed 5.6 millions times annually in the U.S. out of 4.2 billion (1 out of 750 prescriptions), that makes HCQ one-quarter as deadly as the average prescription medication. Those patients taking HCQ who do experience serious complications are not typically short term users. Far more often they are chronic users who consume thousands of doses of HCQ over a long period of time.

Let’s take a look at what the WHO has to say about HCQ/CQ safety:

Despite hundreds of millions of doses administered in the treatment of malaria, there have been no reports of sudden unexplained death associated with quinine, chloroquine or amodiaquine, although each drug causes QT/QTc interval prolongation.

The only issue that we take with this observation is that it understates the number of doses administered for malaria, which in fact goes well into the billions.

Even better, some large studies show that HCQ confers long-term benefits to cardiac health. While the mechanism for which that benefit manifests is purely speculative, it is understood that gradual microbial infection of the heart is a chief cause of heart health deterioration. The unique Swiss army knife array of qualities HCQ brings to the table, including antibacterial, antiparasitic, and antiviral efficacy, seem likely to play a role.

But most every drug can be abused to levels of toxic doses. When it comes to the use of HCQ and CQ as therapeutic drugs, doctors are careful to prescribe enough medication to reach the desired effect, but not so much that toxicity does more damage than good. Both HCQ and CQ have a long half-life of around a month, and effective dosing often involves achieving an equilibrium of the active agents from the chloroquines in a patient’s blood serum. There is a Goldilocks zone for some HCQ or CQ treatment where too little can be ineffective and too much begins to climb into a level of increasing danger. The mere fact that doctors prescribe these medications to millions of Americans annually is proof of their confidence in avoiding toxicity with patients.

Skeptic: But might HCQ be more harmful for SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 patients?

This is the right line of inquiry, to be sure. Let us take a look at several studies examining safety of HCQ or CQ for COVID-19 patients.

In a large literature review (Prodromos et al), HCQ showed to be protective of COVID-19 patients without substantial risk. From that study, the worst of any case series showed HCQ side effects to be non-fatal:

We found one case series describing 251 COVID-19 patients treated with HCQ and azithromycin [36]. A total of 23% developed extreme QTc prolongation. However, HCQ was discontinued in patients with QTc prolongation, and no deaths occurred. (emphasis ours)

We found no reports of cardiac death from [torsade de pointes] or other arrhythmia due to receipt of HCQ. (emphasis ours)

In a Saudi Arabian study (Mohana et al), 2,733 COVID-19 patients treated in outpatient clinics using HCQ showed no serious adverse events. No ICU admissions or deaths were reported at all!

In a French study (Million et al), out of nearly 1,000 patients who received HCQ, no patients experienced cardiac toxicity.

In a U.S. study (Saleh et al), none of 201 patients receiving either CQ or HCQ, 7 patients were taken off the drug used, but there were no arrhythmogenic deaths or cases of torsade de pointes.

In a Chinese study (Huang et al), none of nearly 200 patients given CQ experienced serious adverse events.

The Indian Council of Medical Research issued an advisory recommending prophylaxis use of HCQ in high risk populations after examining 1,323 individuals taking HCQ as pre-exposure prophylaxis, citing seven serious safety reports of which three were prolongation of the QT interval (which usually simply results in the subject being taken off the medication).

In a Turkish study (Bakhshaliyev et al), none of 109 patients given HCQ along with azithromycin suffered clinically significant cardiac events.

In a Brazilian study (Borba et al), a moderate (total) dose of 2.7g of CQ was well tolerated by extremely sick patients, whereas an extremely high (total) dose of 12g of CQ resulted in substantially increased death of patients.

Most all references to the dangers of HCQ or CQ refer to isolated cases, large doses of HCQ or CQ as in the Borba trial, a now retracted paper that many believe was fraudulent, or vague references to extremely rare side effects such as torsade de pointes (TDP). A handful of the many studies on around 200,000 COVID-19 patients receiving CQ or HCQ mention a tiny number of cases of TDP, the several patients who experienced TDP were extremely sick already. While HCQ looks very safe overall for COVID-19 patients, it looks safest when used as a prophylactic or therapeutic for early stage COVID-19 patients, once again affirming the Primary HCQ Hypothesis as the strongest version of the HCQ Hypothesis.

Both HCQ and CQ have mild side effects such as nausea and headaches. These are often recorded as adverse events (AEs) in medical reports, whereas serious adverse events (SAEs) such as prolongated QTc tend to be counted separately. In the U.S. there is a standard grading for AEs on a scale from 1 (the least serious) to 5 (most serious prior to SAEs), and nearly all AEs reported from patients during COVID-19 trials have been grade 1 or 2, where reported. For lower doses of HCQ/CQ used as prophylaxis, even mild AEs are few.

Now, let us examine where we stand with our CBA:

The risks are extremely low, and virtually non-existent for prophylaxis and early treatment.

The cost is around $20.

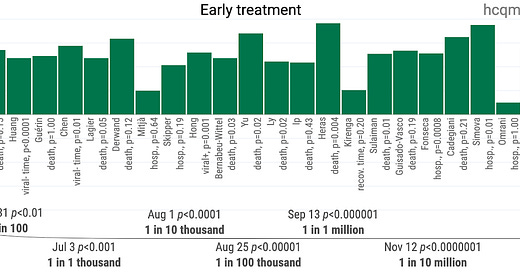

As such, we need only see the slightest benefit for the optimal use of HCQ (usually with azithromycin and zinc) in order to achieve a net positive CBA. We explore the positive effects of HCQ seen in evidence in future articles. In the meantime, take a gander at this.

Note: any recommendation for any medication for any individual still depends on a doctor's examination of the individual. As mentioned earlier, even those prescribing HCQ to most of their COVID-19 patients avoid prescribing it to a few of them---usually either the very young who are likely to recover without it (as per Zelenko's protocol) or to the elderly with heart conditions who are the most likely to experience negative effects of cardio toxicity, rare though they may be.