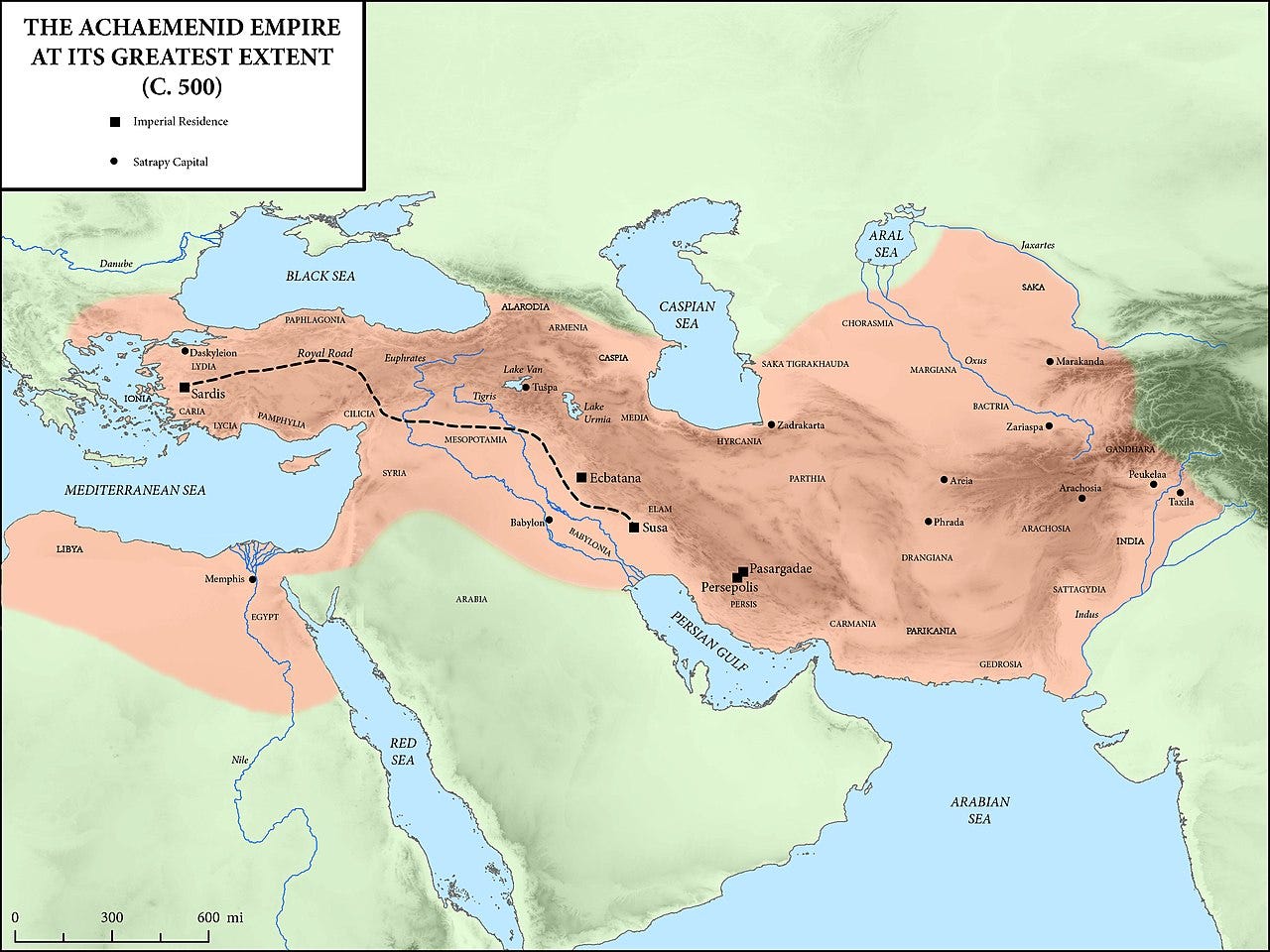

As with much of history, it is hard to know where to begin exploring the history of China's relationship with what we now think of as the West (the Americas, but until recently mostly Central and Western Europe). China's first dynasty, the Xia dynasty, began over 4,000 years ago. For numerous dynasties and thousands of years, Chinese concerns were largely localized---primarily within China itself, but also with surrounding rivals such as the Mongols, Koreans, and various kingdoms of Southeast Asia. However, unique Chinese goods began to make their way west over time. Silk believed to be from China has been discovered in a three-thousand-year-old Egyptian tomb.

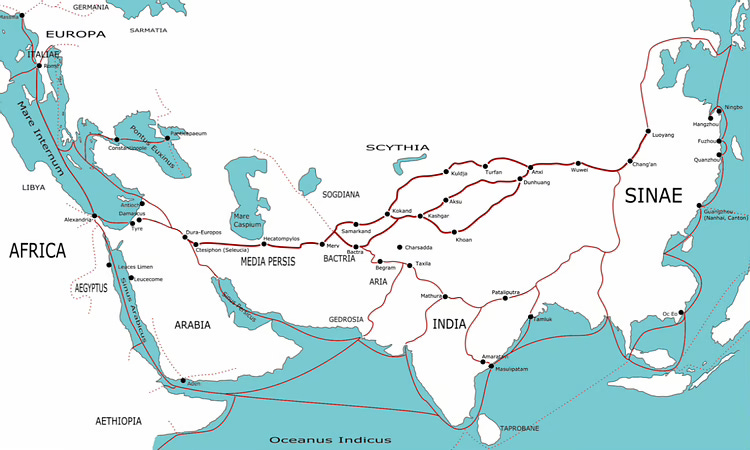

Inevitably, trade of valuable Chinese jade and silk took place along more and more weathered trade routes. Eventually, these routes stretched through India, the Middle East, and into the region between the Mediterranean and Black Seas. While a handful of Europeans made their way to China, The Travels of Marco Polo during the thirteenth century was eye opening precisely because Europeans knew so little of Far Eastern cultures.

Eventually expanding into what has become known as the Silk Road (more accurately route, even more accurately "network", and ever more accurately "trade network"), artisans of China, merchants, travelers and security personnel (sometimes including the infamous shaolin kung fu warrior monks) connected with Europe through largely distant cultural exchange. Distant, but highly motivating. While China burned the Treasure Fleet after a historically brief but dramatic history, desperate Europeans far from the sources of fine textiles and spice invented ocean faring crafts able to round Africa to establish their own trade. Still, only a small fraction of that trade connected directly with China for the first centuries of ascendant European capitalism.

In 1796, at the end of the Qianlong Emperor's reign, the Qing Empire of China ruled over more than one-third of the world's population. For most of recorded history, China generally maintained a technological edge over much or all other nations until the growing wealth and decentralization of Europe promoted a wider and more competitive university network, cultural encouragement of science and the arts, and enterprise that leveraged those advantages into endless arrays of useful inventions.

In the mid-sixteenth century, Portugese traders set up shop at Macau. The Ming dynasty was quite accustomed to maritime trade with foreign merchants from Japan, India, and the Arabian Peninsula. Over the ensuing decades, European trade expanded the most in the region with Spanish, British, and others showing up. The East India Companies of Europe grew quickly powerful while sometimes conquering various nations of Asia. For some time, this only brought greater and greater riches through the ports of China as demand for tea, textiles, porcelain, and other goods poured vast amounts of silver bullion into China. Chinese merchants no longer depended on the emanation of its fine goods into costly trade networks and series of middlemen. Now buyers came to them directly at one of several busy merchant ports.

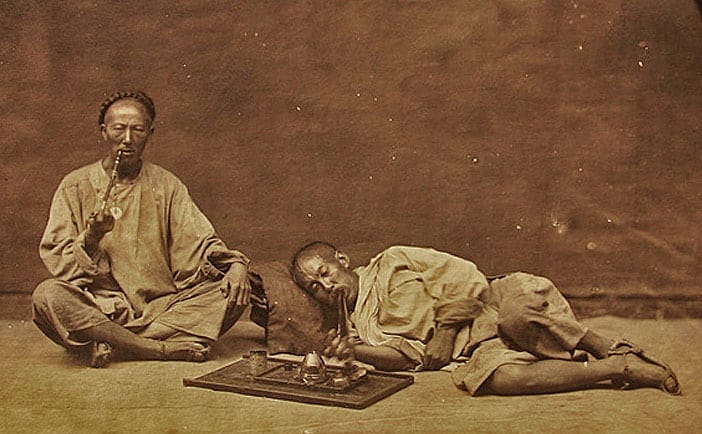

China grew so wealthy from European trade with the East India Companies as to experience monetary supply inflation problems in its domestic economy, not to mention growing cultural pockets of the kinds of decadence that come with excessive capital supply. At various times, China banned forms of tobacco and opium in an attempt to rein in temptations of character of an unofficial burgeoning middle class that often grew upward from peasantry, then sideways or downward.

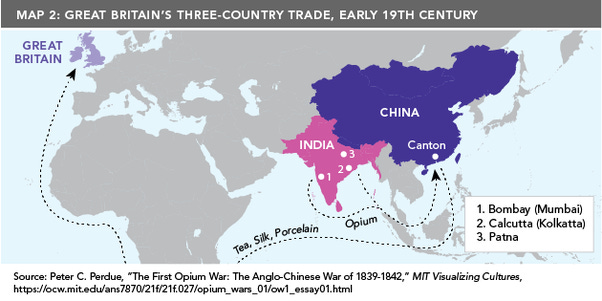

At the same time, the need for monetary supply in the form of precious metals ate up European gains from conquests in the Americas. Demand for Asian goods was thus also at root of mercantilist pressures among kingdoms of Europe that exported precious metals in return for Oriental products. It might be said that, for a while, the Europeans conquered and settled the Americas (reinstituting slavery that was previously banned among most Christian nations) as middlemen for Chinese authorities, though without the direction of the Emperors of China.

Around the late 1700s, the British East India Company found a way to even out much of the vast trade imbalance and keep more of its trade silver. Opium had been received in China from the Moghuls (Gurkani) of Afghanistan and part of modern day India. The fading of Moghul power during the early eighteenth century left a void that British traders gleefully filled, and then expanded, sourcing poppies from Java, Bengal, Malwa, and the Ganges plains. Separation of the agricultural, production, and trade processes allowed the British East India Company an essential monopoly on the opium trade which primarily targeted China. Over a little over half a century, Chinese imports of opium increased twenty-fold, with the British merchants dominating the trade. Earning profits from West to East and East to West, the British East India Company became by far the most powerful corporation in the world.

World power had shifted from East to West with only relatively small military battles taking place from the 1500s to the 1800s. At the same time, the distance between the West and the East grew far smaller. Now China, whose conflicts remained largely internal for millennia, if not limited to near neighbors, faced a new world that its leadership could not have predicted or understood. Like extraterrestrials from another planet, the Europeans came, trading at first, then dominating the neighborhood, one kingdom at a time. Then the alien invaders struck China.

The 1800s included an increasingly difficult series of wars for China. Several times China banned the opium trade during the 1700s and 1800s. The British traders began to ignore such edicts, thumbing its nose at the sovereignty of China, claiming moral justification through the principle of free trade. China began to seize cargo, and in 1839, war broke out between China and Great Britain. More accurately, a three year long war took place between China and a corporation that often made use of the British military. British naval dominance allowed the corporate-national military to pick its targets and attack with unassailable swiftness. China was throttled. During this time, the Qing Empire ceded Hong Kong to Britain, which remained in control of the colony from 1841 until 1997. Most telling were the terms of peace that included the transfer of many millions of pounds of silver, and the right of British accused of crimes on Chinese soil to be tried in a British court under the laws of the United Kingdom.

Fourteen years after the First Opium War, under pressures of the humiliation of what China called "unequal treaties" of peace, the Second Opium War pitted China against the combined forces of the British, the French, and Americans. This time, foreign forces pushed, proving decisive military power away from the seas. Palaces and landmarks were looted and destroyed. The defeated Chinese rulers agreed to further concessions in 1860, including a near-total opening of port and market access, duty-free, for the victors. The opium trade was legalized and Christians were granted civil rights, property rights, and the freedom to proselytize within the empire.

While China began a process of looking inward for new strength, the French came back for more armed conflict during the Tonkin Campaign (1883-1886) during which it put down Chinese resistance led by a warlord with a growing following.

During the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), Japanese forces defeated China in a series of battles demonstrating that China's attempts at military modernization still lagged.

While China's dynastic rulers frequently put down internal rebellions throughout its history, the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901) saw something new. A lame China had opened up to many Christian nations whose diplomats lived there in comfortable semi-permanence while missionaries converted many Chinese to the Christian religion. Anti-imperialist sentiment welled up until militias formed and began to attack both foreign and Chinese Christians. The Eight Nation Alliance of the U.S., Austria-Hungary, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and Russia put down the Boxers, looted Peking (Beijing), and executed officials suspected of fomenting or aiding the rebellion. The Western victors once again extracted silver coinage (over $10B worth in 2021 prices).

In 1911, Qing and Revolutionary armies struggled for control of the nation. The struggle lasted only a few weeks. One of many such conflicts throughout Chinese history, this one ended differently. There was no warlord or powerful prince there to usher in a new dynasty. The long history of imperial China took a final turn. The Xinhai Revolution of 1911 led to the end of the Qing dynasty, but more. On February 12, 1912, the last Chinese emperor, six-year-old Hsian-T'ung, also known as Puyi, abdicated, and the Republic of China was formed.

Much of my older research tracked family fortunes and so many times deep pocket profiteers are on both sides of conflict. Our generic history sources rarely teach us the critical elements. The Forbes clan has deep ties to China opium trade that are rarely noted, nor Chamber of Commerce and DJIA notables operating there for over a century. I can't resist adding ties to toxic history and blue blood titans when the rare opportunity pops up.

https://web.archive.org/web/20081205061609/http://academickids.com/encyclopedia/index.php/Forbes_family