"Power does not corrupt. Fear corrupts… perhaps the fear of a loss of power." -John Steinbeck

Almost everything.

I've been asked many times to teach a little bit about trading—particularly in the cryptocurrency era. So, I'm finally going to do a little bit of that, but for subscribers only. After all, it's good (and sane) to take some time off thinking about the pandemonium.

How It Started and Progressed

In April of 1998, I was a 20-year-old junior and Arthur Holly Compton Fellow at Washington University in St. Louis, and also working full time crunching numbers at National Alliance Insurance Company, a small niche auto insurance outfit that targeted RV owners who turn out to be an identifiably conservative, low-risk group whose kids are usually grown up, and who more often own more vehicles than have members of the household. If that doesn't sound busy enough, I was president of a student-run debate team, and had just started dating my future wife. That month I got a call from a senior VP at one of the quant hedge fund giants, so I flew to New York for an interview. The following week, I was hired. A few weeks later, I was living in Midtown Manhattan, learning the mathematics and processes of bond trading. A few weeks after that, I was tapped to trade a large Asian (mostly Japanese) fixed income account leveraged up to $12B in bonds and $20B notional in interest rate swaps. It was one of the largest buy-side bond accounts in the world. Then a few weeks after that, I turned 21.

Sounds like a wild ride, right? The next few weeks saw the collapse of the Russian ruble and the Long Term Capital Management catastrophe. I also stopped what might have been a historically unprecedented repo market catastrophe, and helped route a custom trade through BNP Paribas to plug the gap. In the meantime, I learned plenty about what would eventually spin into the mortgage bond crisis.

For years after I left finance to build education companies, I was constantly hounded by recruiters for investment bank and hedge fund work, which I figured I could go back to any time. Though when I started adamantly telling the truth about the mortgage bond crisis, that world turned on me, and I learned what it means to be a professional dissident.

All that feels more frustrating to look back at when I realize that the vast majority of the Western Mandarins hold their positions by not understanding any of it, or actively denying it if they do. How can a system survive when it requires such a strong commitment to ignorance?

It won't.

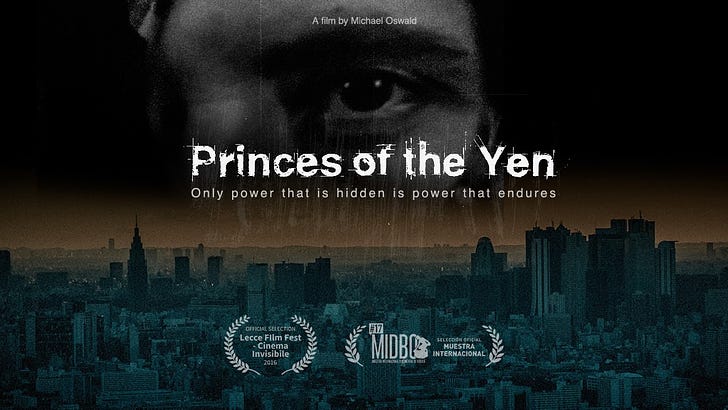

But there are bright spots. I thought I'd never be able to have a conversation about what happened in the Japanese markets until Professor Richard Werner laid out a faithful version of what went down (at least from the top-down monetary side…I'll offer up one of my own stories in a couple of paragraphs). If you don't watch now, I encourage viewing Princes of Yen to get a better sense of the power that the globalist banks have to pick and choose winners—meaning whole nations.

And that's how you engineer a booming economy into decades marred by 11 recessions.

That's also how you engineer China's further economic rise, but that's a story for another day…

Conspiracy Theory as Trading Strategy

Outwardly, high finance is all about high frequency trading and statistical arbitrage games. In reality, it's more about information, and that means speculation about the nature of reality—backed by modeling and research, of course. Some of the modeling is purely mathematical, but also structural.

One of the trades that I inherited when I took over trading in the Japanese markets was a unique one that involved a unique type of bond that you likely never knew existed. A lottery bond is an exotic asset that involves the combination of a bond and some form of lottery. The lottery could be anything: money, rare luxury goods, fluffy bunnies, whatever.

But here's the secret that breaks the naive Mandarin who cannot conceive of the nature of reality that good traders work to possess: if the lottery is valuable enough, it gets rigged. I don't mean that governments might rig lotteries—I mean that they inevitably do so whenever they can get away with it. If you're not cynical enough to understand the magnetic nature of corruption to such opportunity, you're better off not trading. There is a reason that so many day traders go broke.

It is unclear to me whether the design of Japanese municipal lottery bonds was for the expressed purpose of creating an asset to set up a corrupt market, or whether the Yakuza recognized or was introduced to the scheme, but the result was inevitable. Japanese lottery bonds were callable bonds, but with the unusual caveat that the bonds were not called in proportion to holdings (by investors) or at random, but according to a lottery.

Why should that matter?

It matters because governments like to call bonds when they can issue new bonds at lower interest rates. That saves them money. In such an environment, the investor does not want to see their own bonds called. That would mean reinvesting the money at interest rates that would be less profitable. And through the 80s and the 90s, the Japanese economy saw predictably sinking interest rates as it boomed.

I was at the trading desk late one night in 1998 when negative interest rates traded for the first time. I was probably one of the first hundred people on the planet to share the surprise that negative interest rates were suddenly a reality.

The Yakuza fixed every lottery in their favor, usually meaning that their own bonds were never called. As you might imagine, the gradual realization by market participants of the fixed lotteries soured investors on the entire municipal bond market. This became a poisonous sector in Japanese finance, and the lottery bond prices sank.

Please call it conspiracy theory. I'll clean up after you…

As the price of a security sinks, it eventually attracts a different kind of investor, willing and able to measure (and take on) risk. Part of my job was to inquire about lottery bonds while talking with various investment banks who would sometimes buy them or arrange for offloading by smaller investors. I could buy small amounts of the bonds (small relative to the portfolio at least), and then wait to see what proportion of the bonds were called during any one lottery. We would then run a Bayesian analysis to estimate the distribution of bonds owned by the Yakuza. Then we could estimate the proportion of the bonds that would be called, allowing for a solid valuation of the bonds. If the return on investment was high enough to meet our threshold, we would buy them when tranches became available.

It's great to play a game when you're the only player in the market, and that's just the way I like it.