Declining American Health: Vaccines, Toxins, or Both?

The Healthcare Wars, Part 1

I am currently reading Dr. James Lyons-Weiler's book The Environmental and Genetic Causes of Autism. I could have finished it, but there are a lot of citations, and I'd rather go down this road slowly so that I can absorb more of it more completely.

In the meantime, Toby Rogers is exploring the notion that part of the craziness of American politics is that large portions of both partisan pools are vaccine-injured:

I think that he is onto something, and I hope he'll join me for a conversation sometime. I began to have an inkling of something like this while writing a couple of Culture Wars articles (here and here) that I began as a critique of a particular aspect of the trans-advocacy movement, but spiraled into a second article, and then dozens of pages of notes. I stopped simply because I felt it would be a two-week project, which wasn't what I signed on for. But the topic is important, and as I delved deeper, I began to believe that the explosive increase in the number of trans people is likely related to the explosive increase in the number of autistic people. Indeed, those groups overlap pretty heavily.

Those most often afflicted are also male, and perhaps that makes sense given that for the human species, the female is the default, and the processes that have to go right to result in a healthy member of the heterogametic sex are numerous enough that it's not hard to imagine environmental and pharmaceutical poisons disrupting them in a thousand possible ways.

Sometime after I set aside studying trans, Toby wrote an article suggesting that, perhaps, the trans community was targeted with sophisticated messaging [as part of the culture war].

A few hours ago I stumbled on this video by Zach Bush:

While I've heard Stephanie Seneff talk about the glysophate in the Roundup herbicide, I had too many rabbit holes on my plate to explore, so I'm still at the base of that particular mountain of research. (Can a plate have rabbit holes?)

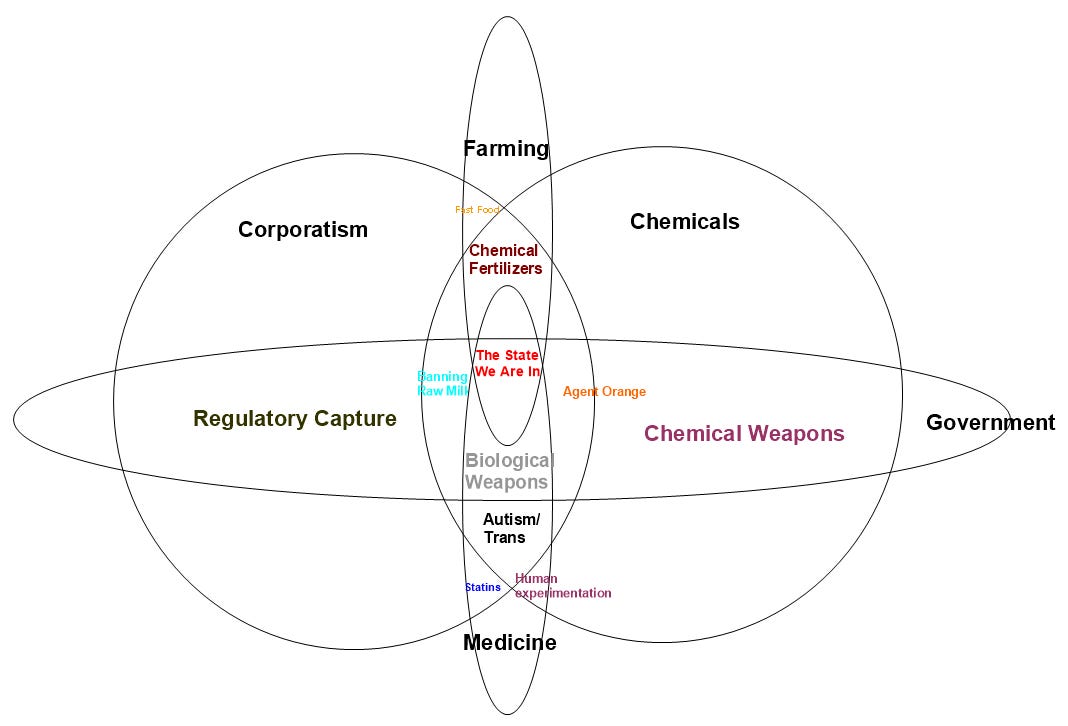

Here is where I am: I suspect that a combination of environment and pharmaceutical poisons are crushing America, and perhaps the West as a whole. Perhaps this is also why corporations seem to be on board some sort of gradual population replacement scheme? (It's just a question, but I'm asking because I'm seeing Big Picture elements come together in a way I had not previously.)

Obviously, as RTE readers surely know, I'm far from naive about horrors of the world, but I had not previously understood the role of poisons to any depth. I see financial corruption quite easily. I've been spotting fake scientific research for 27 years. I'm very familiar with propaganda and psychological manipulation, also. But now I'm beginning to see all that form one big picture along with the ways that various poisons are altering, crippling, or destroying people.

Yeah, sure, I could have put more work into that.

I'm Asking You, Not Telling You

I'm not writing to explain any thoughts I haven't previously explained, but to share an exploration of an intersection of Big Picture problems, and then to ask readers to share their own thoughts, including citations.

Are we in something like the crisis moment when civilizations ignored industry externalities have forced a reckoning?

I'm very pleased to see this. This is long, but you'll probably find a couple of things that are worth your time. I'll start my rambling with my sketchy memory of an old study.

Around 20 years ago, I found a study from the 1970s. The bottom line is essentially this: the researchers were studying the effects of three chemicals on rats. Exposure to one chemical caused no problems. Exposures to two chemicals caused sickness. Exposure to all three chemicals caused death. Around this time, I spoke with someone at the EPA. I asked about how they go about testing the many thousands of chemicals that are in use; how they can test the incalculable combinations of them. He said that they can't aren't funded well enough to test them singly, never mind in the combinations in which they're used. IOW: they're not tested the way they're used in a single product; what about how we all use them together in various combinations in our lives?

The only place that I know of that tested products in this way is (was?) a small laboratory in Vermont called Anderson Laboratories. Using technology that was originally developed by the US Army during the Vietnam War, they expose mice to real living conditions using real products that we all buy: carpet, mattresses, toys, soap, trash bags, or even air samples from buildings that are suspected sources of sick building syndrome. Here's an excerpt from an interview:

“Have you tested pesticides on the mice?

“Rosalind Anderson: We try not to, because we have such frightening results from things that are supposed to be “normal”, like dish-detergent. If that’s so toxic, we really don't want to go to things that are supposed to be poisonous. We avoid pesticides like the plague. Pesticides are a serious problem, but we do not want to risk contaminating our laboratory with pesticides.

“We don't have a ventilation system that is powerful enough. With the ventilation system we have, we would have to take the whole system out, get it decontaminated, take it to the trash and install a whole new system. So we have avoided pesticides as much as we can.”

It's difficult to find information about their work, but a good introduction is this interview. You'll never look at what you have inside your home the same way again. And even if you do manage to clean most of these chemicals out of your life, you will always be exposed to the poisons that people wear on their bodies or use in their homes and places of business.

http://exposed.at/anderson.htm

I became interested in chemical harm due to my own chemical injury. What's interesting in my case is that I had symptom development long before I knew that it had anything to do with the chemical that caused it (formaldehyde) and the chemicals that trigger my symptoms, which are a wide range of commonly used products. The easiest to identify are fragrance products. The worst offenders are those that likely contain phthalates, which led me to read about endocrine-disruptors. From there I found the studies that found frogs could change genders with these chemicals. My suspicion about the trans phenomenon has been that there are any number of traits associated with gender and sex preferences, and perhaps these traits are under the increasing influences of the increasing use of chemicals.

Regarding autism, glyphosate is an obvious potential culprit given the huge increase in use over the same time that autism has increased (same with vaccines), but my suspicion is that the problem may be a combination of things: vaccines, pesticides, and the innumerable chemicals that are in our foods, personal care products, cleaners, and air fresheners. But autism is almost a red flag like cancer: its often the case that if no proof of cancer causation is found, a product is safe. This helps avoid the many problems that are also likely caused by these products such as neurodegenerative diseases, behavioral problems in children and adults, psychological problems, etc.

Obviously, there is a tremendous amount of money at stake along with the power to protect it. The tobacco industry was able to use plausible deniability to defer recognition of harm, but this problem is far more insidious. And far more dangerous.

An interesting blueprint of denial by the chemical and pharmaceutical industries can be found in the treatment of my disease: multiple chemical sensitivity.

https://annmccampbellmd.com/publicationswritings/publication-1/

An alternative hypothesis? Channeling my inner Brett Weinstein, it's hard for me to believe there's not an evolutionary component in all this. Years ago, someone pointed out that the baby boomer generation in America was the first generation to grow up that didn't have to worry about finding something to eat. Years later, we've progressed to a point where many don't seriously worry about any of their other needs - clothing, shelter, medical care - either. The welfare state has certainly helped fueled that, certainly, but that's a separate issue for another time.

Here's the evolutionary component, using the economic concept of wants and needs:

Before the twentieth century, needs were pretty much all that mattered. There was always next winter to worry about, how to survive in a world without electricity or refrigeration, a world in which you were only a crop failure away from severe deprivation and possible starvation.

Needs are few and defined. Wants are unlimited - anything at all that an individual can imagine. Human nature evolved from the very beginning to deal with hard-headed reality. That so many can no longer differentiate between fact and fantasy is predictable, time no longer dedicated to basic needs fueled more time and energy being spent on wants. A credible hypothesis? I believe so.

In a 'Forbidden Planet' sense, the human race has become the Krell.