Art, Mental Health, and Gaslighting: A Review of the 2019 Joker Film, Part 2

The Kunlangeta Part IV

At home, Arthur’s mother writes letters to her former wealthy employer, Thomas Wayne, telling Arthur that the mayoral hopeful is a good man, and must surely be sympathetic to their plight. Arthur reads one of these letters and instead finds that she is pleading for attention and care for their son!

Okay, we’re far enough along in this journey that I’m going to stop reconstructing the film in pure chronological order (if I had even adhered to that so far). We have the setup of a strange, sad man living in the ghetto with his mother, trying to live a decent life despite some form of mental illness that we don’t yet fully understand. But let’s talk about Thomas Wayne, the real joker of the film (seriously).

Arthur, at his emotional low, finds out that, according to his mother, he is the bastard son of Thomas Wayne, and that his mother signed papers helping Thomas Wayne ensure secrecy of all relations. Arthur goes on a journey to find out the truth of the matter---a journey on which he meets Bruce Wayne (just a boy) at Wayne Manor, reaches through the gate, and manipulates Bruce’s face. Probably a lot of the audience doesn’t know what to make of this, but given the way Arthur studies his own face throughout the film, he may be examining Bruce’s teeth, looking for resemblance. If you’re thinking that Arthur isn’t bright enough for that, you’re mistaken. Arthur is brain damaged in a particular way, grossly under-stimulated, and suffers from psychosis, but Arthur shows a resourceful nature throughout the story. Watch it again.

Arthur is interrupted by Alfred, Thomas Wayne’s butler, who proceeds to tell Arthur that his mother is crazy, and that pisses off Arthur who isn’t convinced that he isn’t Thomas Wayne’s son. Arthur also sneaks into a movie gala, and after donning a disguise as an usher, confronts Thomas Wayne in the bathroom. “It’s me, dad!” After telling Arthur that his mother is delusional, Thomas Wayne punches Arthur in the face.

Arthur journeys to Arkham Asylum and requisitions his mother’s mental health file. In it, Arthur finds out that his mother took on a boyfriend who beat the crap out of both of them, almost surely resulting in Arthur’s inappropriate laughing during awkward or painful moments. Arthur’s mother told the interviewer something like, “He was always such a happy boy. I never even heard him cry.”

Right, because the naive mother (and that was her fatal flaw) taught her poor boy to always put on a happy face. So, he repressed the effects of his beatings. Then, for the rest of his life, he repressed the pain inflicted on him by everyone in society.

However, the Arkham files convince Arthur that his mother is delusional, and that her delusions have led to his sad, painful life of isolation. The weight is crushing. He visits his sick mother who is by this point hospitalized, and tells her that he always thought his life was a tragedy, but now he knows it’s a comedy. This can mean a lot of things, but they all come down to one thing: he is a joke(r) to anyone who matters. There is nobody who can care for him, and there never will be. His joy would have value to nobody, but his pain can be a source of amusement.

Arthur then suffocates his own mother with a pillow.

Later, just before Arthur is to appear on his favorite late night television show with famed comedian Murray Franklin, Arthur finds a picture of his youthful mother, with a hand-written note from Thomas Wayne (initialled “T.W.”) who tells her how much he loves her smile. Could these words be innocent? Technically yes, but certainly not. A man doesn’t pen those words to anyone but his lover. Thomas Wayne really is Arthur Fleck’s father. The joke was on Arthur and his mother all along, and now Arthur is guilty of murdering the one and only person who ever loved him.

Also, Arthur Fleck (the Joker) and Bruce Wayne (Batman) are half-brothers, separated by lives of love and disregard in the most disgusting family engineering imaginable. The latter, destined for a materially pampered life, the former destined for a most twisted, mind-wrenching torture: mental and emotional schism. All set in motion by the man who tells Gotham that he is their only hope [as mayor]. What a joker.

Stepping back in the plot fold, Arthur gets a visit from Randal, the bully clown, and Gary, the midget from the clown office who sometimes finds himself the butt of Randal’s jokes. They ostensibly came to console Arthur over getting fired. Arthur says he is in a good mood, celebrating his mother’s death (he doesn’t yet know that she told him the truth). Arthur has dyed his hair green, signifying an acceptance of a new persona that he will carry with him to the Murray Franklin Show. Arthur murders Randal, then lets Gary go, telling Gary that he was the only one who was nice to him [at the office].

While Arthur has suffered a traumatic schism, Arthur still carries with him the basic sense of those who are good to/for him and those who are not. Previously Arthur swallowed all his own pain, kicking the trash instead of an actual person when angry, for instance. But Arthur isn’t just out to kill at random. He is out to kill those who cause him pain, very specifically.

Next we find Arthur, green-haired, face painted, dressed in a vivid red suit, dancing down the stairs out on the street with Gary Glitter’s “Rock and Roll Part 2” playing. Arthur feels good again, having murdered another of his tormentors. But let’s stop here for a moment…Gary Glitter? Gary Glitter fell out of the public light after being unmasked as a pedophile. I strongly suspect that Phillips is reaching out of the film, right at society’s elites. Yes, this is a movie about a horribly abused child who strikes back at his tormentors when stretched to the brink. Distilled madness finding the source as its target. This particular song is a statement. It’s a line in the sand where pedogate is the child abuse scandal of our era, covered up by the elites through the media. No wonder Joker gets such chilled reviews (as we’ll discuss more later). Who’s laughing, now? Arthur delights. This is his triumphant moment of comedy!

(Also, it may be the case that Franklin Murray’s name is meant to connect us to what might be the most famous cover-up of child abuse scandal in American history, centered around Franklin, Nebraska, which pointed to the very top of the American political pyramid.)

What is a joke, anyway? What makes a joke…funny? For the whole movie, Arthur cannot reach past his severed emotional connection with the world to write a single funny line. He imagines a relationship with the adorable single mother down the hall to help pump himself up in a courageous attempt to take the stage at the open mic at a comedy club where he fails dismally. Jokes are subjective, of course (something Arthur observes later on the Murray Franklin show, telling us something about the wide chasm between his intelligence and his ability to connect socially). We find a joke funny when it resolves some kind of tension either that the teller sets up, or that already exists due to the psyche or mental schema of the target audience.

This tells us what’s happening when Arthur kills. When Arthur kills, he resolves tension. Arthur finds the only comedy of his life in the slaying of those who piled up so much abuse on him that he ditched the reality of the moral laws he obeyed for his whole life. This is worse than sad and awful. This should truly horrify you. This should horrify us all. But what should really horrify us all is wondering whether there is anything actually different about Arthur, as a baby being born, joining this world out of a mother, then distanced by an absent father who was perfectly capable of taking care of them both.

Arthur doesn’t get people. Arthur cannot get people. But in his search for comedic brilliance, he hits the head on the nail. To him, that’s worth dancing about.

After getting chased by cops who probably know that Arthur killed the three Wayne employees at the subway, Arthur makes it to Murray Franklin’s studio. Arthur had idolized Murray Franklin who was the subject of some of Arthur’s fantasies. But Murray Franklin got ahold of Arthur’s pathetic attempt at stand-up comedy and mocked it on air, which Arthur saw from the hospital room where his sick mother had been recovering. Now Arthur has been invited to the show to once again play the clown, but insists on appearing as the Joker.

What’s the difference between a joker and a clown, anyhow? Arthur had been a clown, somebody who mocks himself. A joker resolves tension. Arthur confidently smokes a cigarette and takes the stage, kissing the female guest and revelling in the moment. After some back-and-forth with Murray Franklin during which Arthur admits to the slaying of the men on the subway, and Murray Franklin mocks Arthur’s pain as “so much self-pity”, Arthur murders Murray Franklin in front of a live audience.

Throughout the movie, the trash strike and other tensions present in the city have inspired throngs of protesters out onto the streets. They’ve adopted clown masks to show a kind of appreciation for the clown murderer of the three psychopathic corporate goons. These Antifa-like protesters are not Arthur. They are angry. They are at odds with the governing elite. But they know nothing of the true nihilistic extremes that Arthur found (or that found him). But as Arthur is driven away by a police car, some of them ram a truck into the police car, and drag Arthur out. Meanwhile, one of the protestors recognizes Thomas Wayne, ushering his wife and child Bruce away from the chaos through an alleyway, and gun downs Thomas and his wife.

A dazed Arthur regains consciousness, realizes that the chaotic protesters around him are cheering for him, and finally connects with an audience.

In the last scene in the film Arthur speaks with a psychiatrist at Arkham Asylum. Like the social worker, she lacks the ability to connect with Arthur. She shows no intention of understanding him or what he’s been through. She asks questions that don’t relate to his story or his madness. He laughs. She asks what’s so funny. He smiles, “You wouldn’t understand.” Next we see Arthur strolling, care free, out of the room, tracking bloody footprints. He gets chased by a guard.

That’s a wrap.

In my organization, I left out a few important details. One of those is the presence of black women in Arthur’s life. Arthur lives in the ghetto, and most of the people around him are black including the social worker in the early scene, a woman on the bus who chides Arthur for attempting to clown for her son, the single mother whom Arthur fantasizes about, the only black person in the theater where Arthur confronts his father, and finally the psychiatrist he murders. In Gotham, as in most of American history, black women are the least respected members of society, at least ordinarily speaking. Who has less respect? Aside from criminals, it’s the mentally ill. Throughout Joker, we see clearly that Arthur is so low in the estimation of society that he is below every one of these women in power and respect. However, while politics has begun to catch up with the elevation of black women, at least rhetorically, we still live in a world in which terminology surrounding the mentally ill still gets weaponized as insults, and the mentally ill themselves are largely removed from common public presence, by encouragement or coercion. We closed the mental hospitals, so prisons and streets “house” the worst off.

Except the narcissists. Why the narcissists? What do we do with them? In the case of Thomas Wayne, we elevate them! They tell us that we “may not realize it, but I’m their only hope,” and many a Penny Fleck believes that everyone must think so. Through her rose-lensed heart, she just knows that he will take care of her. She cannot fathom what evil he has wrought.

Narcissism is generally a co-affliction. It goes hand-in-hand with psychopathy, sociopathy, or more debilitating disorders to the afflicted such as borderline personality disorder. Narcissism is the crafted veneer that passes a monster off as a hero, or at least highly normal. Neurotypical. It can be easy to detect in some cases, but is usually hard due to survivor bias. The dumb narcissists get no attention from their prison cell. The bright ones thrive. And reproduce.

Arthur Fleck is no narcissist. In fact, that’s why there is no in-between for him. Either he is committed to handling the world in a moral fashion (“I don’t mean to make you uncomfortable”), or straight-forwardly murderous with no apologies (“You get what you fucking deserve”). Penny Fleck gets declared narcissistic, but is more simply delusional in a post-traumatic commitment to her naive existence. Franklin Murray is narcissistic (“It’s a clean show”). Thomas Wayne is pathologically and brutally narcissistic (“She’s crazy” *WHAM!*).

One of my friends dove head-first into the unreliable narrator aspect of the story and debated whether anything at all happened. While not unreasonable, we can really insert such a proposition into any tale. But I don’t think that we should unless and until we’re given a direct and decipherable cue. Besides, Joker is billed as an 'origins story'. I don’t think, “This is what an insane person told a psychiatrist he disliked and promptly murdered,” is very interesting at all. But the story, as told, with appropriate subtraction and accounting for the clearly presented moments of Arthur’s imaginary friends, is particularly poignant, and makes for a spectacular Rorschach test.

As such, I did not interpret Arthur as having killed the Zazie Beetz character. In a terrible moment for him, he enters her apartment instinctually seeking some kind of comfort that he has imagined for himself, from her. That’s when we find out that he imagined it all. “I really need you to leave. My little girl is sleeping in the other room.” Arthur marches down the hall to his own apartment and we see him laughing that uncomfortable laugh of moral-Arthur who laughs at his pain and awkwardness. She never delivers him any pain, and as with Gary, he has no reason to harm her. He’s quite embarrassed to have made her afraid.

Critics Addendum

While this review could stand alone, it shouldn’t. Joker (the movie) reaches out into our world, and so shall I. I’ve claimed that the critics, the professional sense-makers of art in our society, have it all wrong, but I’ve only barely scratched the surface. To skip this part of the exercise would risk the Joker reaching directly into our world.

While millions of Americans pour into theater seats to behold Joker, the New York Times film critic A.O. Scott really throws his energy into making dismissive comments. You’d think anyone who writes, “To be worth arguing about, a movie must first of all be interesting,” and refers to the film as, “afraid of its own shadow, or at least of the faintest shadow of any actual relevance,” and brands its defenders with labels like “bad faith, hypersensitivity, and quasi-fascist groupthink,” wouldn’t bother following up with six additional paragraphs. The inept paragraphs that follow are punctuated by a shallow description of Joker as “less a depiction of nihilism than a story about nothing,” which is one of the greatest self-pwns in the history of art critique, and that’s no small feat. Fortunately for Scott, his embarrassingly obtuse attempt at a snub is behind a paywall.

Writing for the Guardian, Peter Bradshaw calls Joker, “the most disappointing film of the year,” then pens off a shallow synopsis that ends by describing the main character’s transformation as “humiliation and despair become too much to bear, Arthur gets hold of a gun and discovers that his talent is not for comedy but for violence.” Hear that, guy-taking-a-life-threatening-beating? Raising a hand back at your tormentors in self-defense is just a pathetic form of self pity. Listen to your betters and put on a happy face, why don’t you? Bradshaw cannot see through his own cognitive dissonance to make the connection between what he misses about Arthur’s story and the separate vector of the populist movement that adopted his likeness. After some historical discussion of Scorsese and De Niro, Branshaw laments that Joker couldn’t somehow further punish incels and internet trolls, demonstrating his inability to love his enemy: the impoverished [in any form]. That’s okay, I bet he has black friends.

At the New York Post, Sara Stewart calls Arthur Fleck “a violent maniac” from the get go. To be fair, Stewart at least references how, “Arthur Fleck sheds his sad-sack chrysalis and emerges into full-blown Joker mode,” but she goes on to explain to us exactly how she missed essentially every important facet of that story while making use of a solid SAT vocabulary and more advanced phrases like “Kabuki-esque”. In the end, all she can do is to “imagine that Phillips embedded this one with a wry message: Toxic masculinity is, actually, no joke at all,” for which she provides no further discussion and seems to aim at Arthur himself without a single word in her review about Thomas Wayne (or Rupert Murdoch, ahem).

At Roger Ebert dot com, Glenn Kenny pans Joker so that Ebert doesn’t have to take on the task. Like a few other commentators, Kenny makes some historical references to Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy. He questions whether Phillips “really cares about income inequality, celebrity worship, and the lack of civility in contemporary society,” while demonstrating no understanding that Phillips portrayed these as effects of the larger root cause. As with most “elite” reviewers, I strongly suspect that Kenny’s lashing out demonstrates either narcissism covering for his role as a sociopathic underling of a psychotic elite or narcissism covering for borderline personality disorder. Aw, heck, I’ll do the polite thing, feign Hanlon’s razor, and say that I’ll assume he’s just not that bright.

Okay, I don’t know who this Mark Hughes guy writing for Forbes is, but he either missed the memo or Forbes, a news source dedicated to covering billionaires, is one of the rare journalistic organizations that doesn’t fear what the elite might think of Joker. It would take me a few more pages to go into why this doesn’t really surprise me, so I won’t. But while Hughes liked the movie very much, his review is still rather thin given the subject matter. For all I know, it’s just another advertisement, but I honestly don’t know whether I should just assume so or not.

Dozens of other professional reviewers missed most or all of the point, intentionally or not. Many dig into the white maleness of the film, hammering home the beleaguered point that telling a story about a while male is some kind of crime these days, while simultaneously missing the commentary about the many black women throughout the movie. Even when Time spots most of the black women, they invert the device implying that they “are visible but they are not seen”. Ironically, Time missed the brief (though certainly not trivial) placement of the black woman in the theater. Unlike other reviews, the Time review mentions the actual existence of Thomas Wayne (and Alfred) in the movie, but only insofar as “they are more palatable to a core audience which predominantly looks like them.” Somehow Time missed the point that these white men were the primary villains, and that was quite clearly in contrast to the various black women whose flaws were more ordinary and understood on an ordinary human level.

On the topic of mental illness, the Hollywood Reporter thinks that Joker “shouldn’t have relied on [it]”, then goes on to cite several jokers psychiatrists who conclude that it’s irresponsible to suggest a primary link between mental illness and violence. Instead of digging into the specifics of Arthur Fleck’s life, and numerous reveals, they dismiss his suffering as “cultivation of a grievance” and then wind up talking about mass shootings and Trump, because they cannot escape that their job is to insert specific political narratives into anything and everything, no matter how large the problems they ignore and how deliberate that looks. In doing so, they affirm the movie’s theme.

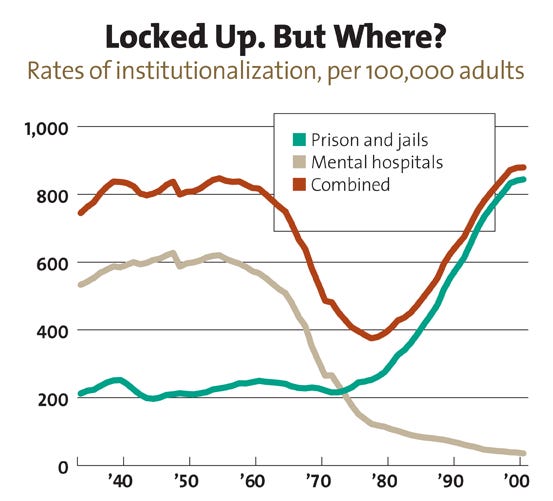

Not entirely unrelated, perhaps now is an appropriate moment to view this graph from thinkpress.org:

The Hollywood Reporter doesn’t get it all wrong in its muddled article (we should be thinking about the world as mass shooters see it, and Joker provides one fictional anecdote), but incorrectly concludes that Joker blames all violence on mental illness, or something like that, and fails to focus on the events of the movie. I sometimes wonder whether we were all watching the same flick.

Then there is this post by “best selling author” E. Michael Jones of Culture Wars Magazine: “The movie pushes these disaffected, young white men towards nihilism. They want you to go out and pickup a gun, and they’re praying that this happens.” No, E. Michael, or Mr. Jones, or whatever you’d like for me to call you, the writers of the movie want for us to think about unaddressed root causes of nihilism. Maybe you should adjust your bow tie to help you tune in.

Addendum (2021): Maybe I was wrong about all the critics misunderstanding the film. Maybe the intellectual art elite were simply practicing for the great moment of gaslighting in the history of Western civilization?

Addendum (2021): I just found this "Top 10 Joker (2019) Moments" video on YouTube that stands out as almost mocking of whatever portion of the audience is bound not to understand the film, but be entertained by a bizarrely simplistic and superficial take on the film:

While I’ve focused here on the elite movie critics, I did read a handful of reasonable reviews (mostly imperfect, but with some good sense and I at least know the reviewer cared to watch the film before deciding what to write) once I made a few internet searches for specific terms. Most all of them were at outlets I’d never heard of, which is interesting in itself. That includes a reddit thread that links to a small time YouTuber making the link to fatherlessness. Perhaps we must simply accept the need to talk with regular people and each other about the pressing issues of today, and come to conclusions using the amazing thought organs that we possess. Maybe that’s the best way to prevent ourselves from being gaslit by uncaring narcissists who want power of society, but have no intention to use power to care for anyone, much less children.

"the well educated critics whose keen minds we depend on when analyzing any art"

Miles Mathis, a classic realist artist, writes extensively about the world of modern "art" and the people who inhabit it.

I couldn't do it justice in a summary, save to say the art market is the largest *unregulated* market in the world, and encourage people to read one of his papers- "I Would Like to File a Suspicious Transaction Report on the entire 20th century." https://mileswmathis.com/launder.pdf

In my case, one of Mathis' papers got me hooked and I've gone on to read a large portion of his site. https://mileswmathis.com/updates.html

Your review of Joker was spot on, it represents the intention of the film well, and hopefully represents what people take home. I don't think the major reviewers missed the point, I think it's precisely their job to herd us away from content like this. I'm happy to say I didn't pay any attention to the criticism and did eventually see the film. What's most surprising is seeing a movie like this being *allowed* to be made in this day and age. I think the fact that it never veers too close to real-world specifics might explain that.

Mathew,

I found your ‘review’ touching and to your point I think, oddly relevant in the ‘but for the Grace of God goes any one of us’ sort of way as I did the when I first saw the film.

You’ve managed to articulate some of what I felt then. I certainly understand the film a lot better now. Your review has really helped, as has having had the time to reflect on the film itself since it’s release.

Thank you

Etienne